Pasts Imperfect (7.4.2024)

Greek Ceramics, Ancient Egyptian Pigments, Silk Roads of the Kushan Empire, Conch Trumpets & Much More

This week, ancient historian Javal Coleman and archaeologist Cole Smith discuss Greek ceramics, amphora studies, and whether understanding transport jars might allow us to better model issues like human trafficking in the ancient Mediterranean. Then, self-help books for the ancient reader, analyzing Egyptian pigments at the Brooklyn Museum, reconstructing the role of the Kushan Empire on the Silk Roads, a new book on Erasure in Late Antiquity, fashion and the Olympics, Chaco Canyon conch trumpets, ancient scribal practices and disability studies, a new issue of the translation journal Ancient Exchanges, an online lecture on Greek, Maya, and Moche Pottery, ancient world journals, and much more.

A Hammer and a Nail? Greek Amphorae and the Movement of Enslaved Greeks

by Javal Coleman and Cole M. Smith

Within the field of ancient Mediterranean archaeology, the transport amphora stands tall—literally and metaphorically. These vessels, also called wine or transport jars, were the most common non-perishable shipping containers of the ancient Mediterranean However, given their size, weight, and abundance, transport amphoras can be the bane of an excavation. Nevertheless, these humble vessels deserve our attention. Why? Not only because they allow us to understand the logistics and networks that constituted ancient economies, but also because understanding their movements may provide us as a pivotal model for reconstructing human trafficking.

What, exactly, did they transport? These vessels contained trade goods such as wine, oil, fish, fish sauce, grain, and fruit. Transport amphoras, like their ornate household cousins, come in varieties that showcase creativity and innovation. Local potters often created transport amphoras with unique elements distinct to an area, like varied handles, necks, or rims; and stamps, painted bands, or graffiti. Regional potters, however, also had the tendency to copy one another, which can make identification and dating of amphoras more difficult.

For ancient historians and archaeologists, the most coveted feature of a transport amphora is a stamped handle. Only a fraction of these vessels were stamped. The presence of a stamp would give the consumer and seller an indication of an amphora’s origins. A consumer of fine wine might keep their eyes out for those amphorae with a Mendean or Rhodian stamp, for example. These stamps could also verify quality or amount. They are evidence of standardization and the work of agoranomoi (Greek market overseers).

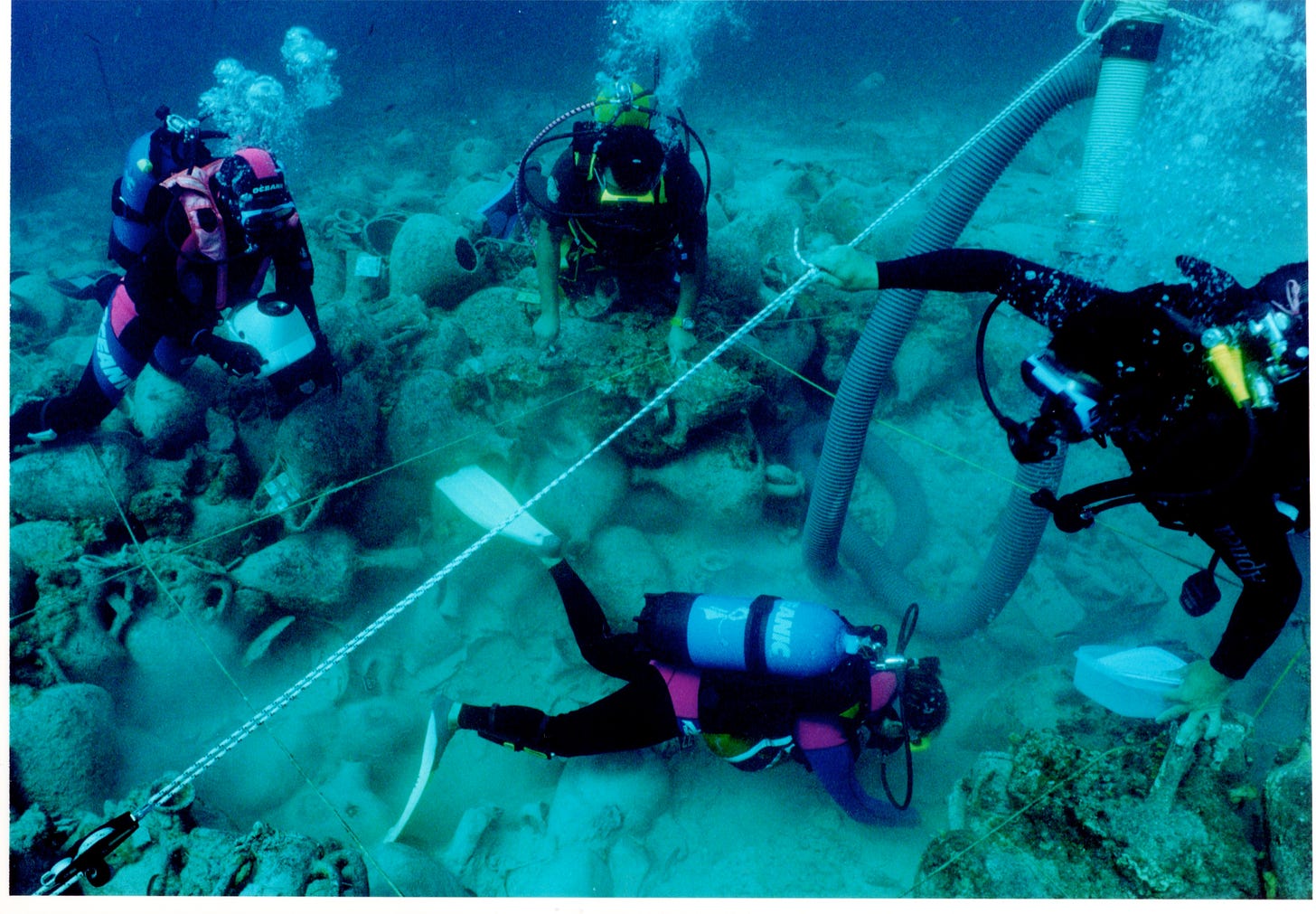

Transport amphoras existed from the Bronze Age (3300-1200 BCE) into the Byzantine period (330-1453 CE). Other neighboring cultures beyond the Greeks and Romans had similar types of transport and storage jars as well. Shipwrecks remain one of the most insightful sources of evidence on these amphorae.1 Between 1991 and 2001, the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) located a Classical Greek shipwreck (440-425 BCE) at Tektaş Burnu (modern Turkey), which was transporting more than 200 transport amphoras filled with wine, pine tar, and beef. While the Tektaş shipwreck informs scholars about trade, it also shines a light on the production of the containers through the presence of amphora stamps featuring the ethnic abbreviation for the Ionian city of Erythrae (ΕΡΥ).

While a considerable number of scholars have studied the transport amphora, two women stand as the true pioneers in the study of these large jars: Virginia Grace and Iraida B. Zeest. Grace (1901-1994) spent a lifetime advancing studies of the amphora. She earned her PhD in 1934 with her work on the stamped amphora handles of the Athenian Agora. Her life’s work remains an invaluable tool to those who study amphoras, especially with her archive housed in the collections of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA).

Lesser known in English-speaking spheres is Soviet archaeologist Iraida B. Zeest (1902-1981). Zeest similarly progressed amphora studies in the USSR, including her studies of Greek and Roman material found on the Crimean and Taman peninsula, in the northern Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. She is credited with starting the Soviet school of amphora studies. Her work raised questions about the spheres of impact of Mediterranean cities such as Miletus, Corinth, Rhodes, and Athens, as well as on how the markets of the Cimmerian Bosporus functioned in the first centuries CE.

But can amphora studies tell us about more than just transport of foodstuffs? Recent studies on the history of the Black Sea region have demonstrated how we might understand the movement of enslaved individuals in the Greek world through examination of such amphoras, especially in their use as containers of wine. Passages from historians such as Polybius (4.38) or the geographer Strabo make it clear that enslaved people were transported across the sea along with amphoras and other trade goods. Both authors also mention how enslaved individuals were exchanged for wine as well. This is Strabo’s (11.2.3) description of trade in Tanais (on the Sea of Azov):

Tanais is settled on the river of the same name and the lake, a foundation of those Greeks who hold the Bosporus. Recently King Polemo completely sacked it in its disobedience. It was a common emporium of the Asian and European nomads and those who sail the lake from the Bosporus. The former bring slaves and hides and other goods of the nomad, while the latter bring in exchange clothing and wine and the other goods associated with a gentle lifestyle. (trans. via Braund)

In his work on Black Sea amphoras, ancient historian David Braund argues that understanding the significance of amphoras in the Black Sea region means setting them in their local and economic context, which includes enslaved individuals as commodities. Recently, Chris Parmenter has also raised the possibility that Greeks might have often exchanged enslaved persons for wine. David Lewis even presented the possibility that the transportation of amphorae and enslaved persons led to shipwrecks and disasters in some cases.

These studies all ask us to consider: How might we better understand the movement and exchange of enslaved persons through careful examination of the context(s) of different amphora networks? It seems reasonable to move past the simple literary investigation of issue like slavery networks and pursue a more material approach. Ancient ceramics are worthy of study on their own; however, they may also provide important models for reconstructing supply chains, shipwrecks, and human trafficking in the ancient Mediterranean world.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

Let’s lead with a laugh. I hooted so loudly swiping through this carousel from the New Yorker that I startled the dog. Cartoonist Dahlia Gallin Ramirez has a great piece on “Self-Help Books from Ancient Times.”

Love color history? Egyptologist Morgan E. Moroney, the Brooklyn Museum’s Assistant Curator of ECANEA, has a great essay on “The Many Shades of Ancient Egyptian Pigments.” While putting in a new installation within the Brooklyn Museum’s ancient Egyptian art galleries, museum staff took the chance to analyze the Egyptian pigments in the collection. They used “noninvasive techniques including MBI (Multiband Imaging) and pXRF (portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy)” to look at pigment lumps excavated in the 1930s at the New Kingdom site of Tell el-Amarna. It is particularly exciting that they identified Egyptian green frit.

According to the South China Morning Post, the first phase of a joint partnership between Chinese and Uzbek archaeologists to examine the Kushan Empire’s (c. 45-230 CE) pivotal role on the Silk Roads is now complete. Working in Surxondaryo, an area within southeast Uzbekistan, archaeologists found a number of houses, artifacts, and burials. For more on the history of the Silk Roads, see Xinru Liu’s splendid The Silk Road in World History, which you can borrow for free from the Internet Archive.

There is a new issue of the translation journal Ancient Exchanges out now. The theme of the issue is “Bloom” and features (to name but a few): Jia Self's in-class translations of Catullus 64 through the lenses of metaphrase and paraphrase, Kristina Chew's thrilling translation of Simonides' ten types of women (plus In the Classroom essay). Music and song bloom in Diane Arnson Svarlien's metrical translation of Rimbaud's Ver Erat (an expansion on Horace, Odes, III. 4 (9-13, 18-20), Marie Orise's musical cí by Classical Chinese poet Li Yu, an Old Norse song translated by Nik Gunn.

Particularly exciting is the cover art and artwork selection from Laura Dolp's "Where I hoped a rock would be" (2022-2023), collaged images and text created from traced aerial maps of Ħaġar Qim, a temple site located in Malta from a prehistoric civilization that existed between 3600 and 2500 BCE.

A new open access book, Erasure in Late Antiquity, edited by Kay Boers, Becca Grose, Rebecca Usherwood, and Guy Walker is out now and free to download. I really enjoyed Mali Skotheim’s chapter on “Spolia and Epigraphical Erasure at the Church of Mary in Ephesus” and Mark Humphries’ concluding remarks on “Erasures and Rewritings in Space and Time.” Silence and erasure speak volumes, as it turns out. Additionally, there is a new article on “A Prison in Late Antique Corinth,” by Matthew D. C. Larsen, and “Down the drain: reconstructing social practice from the content of two sewers in a Late Antique bathhouse in Jerash, Jordan,” free in the new JRS from authors Louise Blanke, Pernille Bangsgaar, Stephen McPhillips, Raffaella Pappalardo and Tim Penn.

In ancient medicine news, the authors of Medicine, Health, and Healing in the Ancient Mediterranean (500 BCE – 600 CE) published an Instructors’ Guide for teaching the book here. Additionally, the newly launched Carminabase is “an online database, collectively developed and freely accessible. It gathers charms, that is to say incantation formulas aiming to bring a remedy or to exert an effective action on men, animals or plants, from medieval manuscripts.” Finally, HistMed historian extraordinaire Monica H Green also has a new article on “The Pandemic Arc: Expanded Narratives in the History of Global Health.”

There is a new open access article in Scientific Reports on disability and ancient Egyptian scribal practices, “Ancient Egyptian scribes and specific skeletal occupational risk markers (Abusir, Old Kingdom).” Criss-cross applesauce? Bad for your back, but there are other skeletal factors to assess for those writing hunched over with a clenched jaw for too long. Not that any of us would know about that…

The Paris Summer Olympics are fast approaching, and at least one PI editor is on the edge of her seat watching the Olympic trials. Fashion houses are revving up, too. One has to imagine the ancient Greek pantheon looking like this.

Tiptoeing into the early modern world here, but a recent article from American Antiquity suggests that English settlers at Jamestown ate Indigenous Tsenacomocoan dogs in times of need. Shocking, too, is the replacement of Indigenous dog heritages with European breeds over the course of the early modern period.

This is the opera/classical reception crossover that I hope PI readers want to see: The Comet/Poppea, an opera from the LA-based company The Industry. W.E.B. DuBois? Monteverdi opulence? Italian and English?? Come on, look at this set.

Before landlines and cell phones, how would you get your neighbors to come outside to play? Ancient Pueblo inhabitants of Chaco Canyon (850-1150 CE) in modern-day northwest New Mexico were doing a lot more with less. Enter: the conch trumpet! Used to communicate with smaller communities outside of a central “great house,” the very loud sound of a conch has now been mapped as an ancient soundscape by anthropologist Ruth Van Dyke and her team. Seventh-grade me is still haunted by the conch in Lord of the Flies. Anyone else?

Repatriators: they’re just like us. NPR reports that a D.C. woman thrifted a vase on clearance for four bucks … and it turned out to be a Mayan vessel more than a millennium old. Now it’s back in Mexico, living in its temporary home at the National Museum of Anthropology before it finds a permanent residence in another museum.

"I got an email saying, 'Congratulations — it's real and we would like it back.'"

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Iranica Antiqua Vol. 58 (2023)

AOQU (Achilles Orlando Quixote Ulysses). Rivista di epica Vol. 5 No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

Memoria e rielaborazione dell’epica antica nella cultura del “long Eighteenth Century”

Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie Vol. 106, No. 2 (2024) NB René de Nicolay, “Philosopher-King on a Leash: Combining Plato’s Republic, Statesman and Laws in the Justinianic Dialogue On Political Science”

Early Science and Medicine Vol. 29, No. 3 (2024)

Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica Vol. 50 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess

New Classicists No. 11 (2024) #openaccess Human and non-human animals in Antiquity

Karanos Vol. 6 (2024) #openaccess

Circe de clásicos y modernos Vol. 28 No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

I quaderni del m.æ.s. - Journal of Mediæ Ætatis Sodalicium Vol. 22 No. 1 (2024) #openaccess The Boundaries of Religious Dissent: A New Approach to Heresy in the Middle Ages

Faventia Vol. 44-45 (2022-23) #openaccess

Scripta Classica Israelica Vol. 43 (2024) #openaccess NB Sabrina Inowlocki “What Caesarea Has to Do with Alexandria? The Christian Library between Myth and Reality”

Manuscript Studies Vol. 9, No.1 (2024) #openacces

Medieval Worlds Vol. 20 (2024) #openaccess Moving Jobs: Occupational Identity and Motility in the Middle Ages & Cultural Brokers in European and Asian Contexts. Investigating a Concept

Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia Vol. 30, No. 1 (2024)

Classical Philology Vol. 119, No. 3 (2024)

International Journal of Divination and Prognostication Vol. 5, No. 1 (2024) NB Lisa Raphals “Early Chinese and Greek Accounts of Chance and Randomness”

Journal of Indian Philosophy Vol. 52, No. 3 (2024)

Archäologische Informationen Vol. 46 (2023) #openaccess

Erga-Logoi Vol. 12, No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

Digital Scholarship in the Humanities Vol. 39, No. 2 (2024)

Mnemosyne Vol. 77, No. 4 (2024)

Hesperia Vol. 93, No. 2 (2024)

The Vatican Library Review Vol. 3, No. 1 (2024)

Revue de métaphysique et de morale Vol. 122, No. 2 (2024) Les paradoxes dans la philosophie antique

Journal of Ancient Judaism Vol. 15, No. 2 (2024) Antiochus III’s Decrees for Jerusalem: Between Imperial Stress & Local Agency

Revue d'Etudes Augustiniennes et Patristiques Vol. 69, No.2 (2023

Lectures, Workshops, and Exhibitions

At the Getty Villa, they have an upcoming online lecture: “Stories on Ceramics: Time, Transformation, and Touch” on Thursday, July 11, 2024 | 12-1 p.m. PT. To watch online via Zoom, register here. The lecture goes with the current exhibition Picture Worlds: Greek, Maya, and Moche Pottery, which “brings together painted terracotta vessels from three distinct cultures. To explore what we can learn from seeing them side-by-side, three experts each select an example for close looking. Together, they address time, transformation, and touch in the depiction of mythical tales, and the powerful role these painted vessels play in the sharing of stories.”

On July 9, 2024, Alon Dar, doctoral researcher on the 'Social Contexts of Rebellion in the Early Islamic Period (SCORE)' team, will present his “work on contentious elites in the early Islamic period” with a lecture on: "Rebellious Notables: Provincial Revolts in the Islamic Caliphate (8th-9th Century CE)”. The event will take place next week on Tuesday at 4 pm CEST, on Zoom. If you'd like to register for the talk, please send an email to score.aai@uni-hamburg.de.

The ISSE Online Conference 2024, “Past Perceptions, Modern Perspectives: Contextualising Egyptomania” will be on August 10 and 11, 2024. Tickets are here. As they note, “This conference aims to explore the historical background and evolution of Egyptomania, whilst engaging with modern perspectives of heritage and reception studies. ISSE is dedicated to embrace the need to engage critically with the subject, considering the ethical implications of our (ongoing) fascination with Egypt's ancient heritage and future directions for research.”

For example, the Late Bronze age Uluburun shipwreck, discovered in 1982 off the southwest coast of Turkey, contained Bronze Age Canaanite jars indicating numerous cargo types including glass beads, olives, and Pistacia resin.

Thanks, always interesting and entertaining!

Any ideas about the provenance of Chaco Canyon's conch trumpets? Dates/trade routes? ---A. Sanford