Pasts Imperfect (9.26.24)

Ancient Heresiology & Project 2025, Drinking Tobacco, Naming Palestine & More

This week, historian of early Christianity Shaily Patel discusses heresiology, rigid binaries, and the idea that “orthodoxy is violence.” Then, late antique cliff monasteries, drinking tobacco in ancient Guatemala, a Jewish gladiator at Pompeii, cheesemaking in Britain, myth-busting the idea that the name Palestine is “a Roman invention,” a tribute to historian and translator Peter Green (December 22, 1924 – September 16, 2024), new ancient world journals, and much more.

On Political Orthodoxy: Or, How to Read Project 2025 by Shaily Patel

Around 374/5 C.E., Epiphanius of Salamis produced his Panarion, a fascinating example of late ancient heresiology. In the study of early Christianity, “heresiology” refers to a genre of literature dedicated to making and marking difference between an author’s own orthodoxy (i.e., what they deem “correct” belief and/or practice) and supposed heresies, that is, groups, beliefs, or practices ancient heresiologists deemed “incorrect.” In his introduction, Epiphanius claims his work will catalog “names of the sects and [expose] their unlawful deeds like poisons and toxic substances” (Proem.1.1-2; trans. Williams). He says these supposedly heretical sects are the “bites of wild beasts” and that his Panarion, or “Medicine Chest,” offers a panacea for all such venomous and lethal heresies (Proem.1.1-2).

But Epiphanius does not stop at dehumanizing and misrepresenting his opponents. The Panarion gazes back into cosmic history to suggest that piety and faithfulness – precursors to his orthodoxy – existed long before Jesus Christ (1.2.4). Likewise, the raw material for heresies, “the evil teachings” of magic and astrology, were also preexistent (1.3.3). This move allows Epiphanius to fold all history and attendant historical phenomena, from the mythic past into the far future, into a decidedly Christian history. This is how heresiology works: It forces a fight on its own terms, using its own standards, whether or not opponents subscribe to the same terms, standards, or even view themselves in an existential battle at all.

Heresiology has long simplified the world. It creates tidy conceptual binaries where we know complexity reigns. For instance, Epiphanius’ move to reduce all beliefs and practices into orthodoxy or heresy ironically disregards Christianity’s own history. As early as the letters of Paul, we have evidence of Christ-believers adopting a range of beliefs and practices. Christianity has never been one thing, but heresiology demands the centering of one “correct” form of the tradition to pit against multiple heresies. As an intellectual project, therefore, heresiology cannot allow for multiplicity; it cannot trade in grays. This is a particularly harmful feature of the genre and one that is unfortunately a part of modern US politics as well. Take Project 2025, a lengthy series of policy proposals developed by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. The Trump-Vance campaign has distanced itself from this project, but its authors clearly envision their proposals being adopted by the next conservative presidential administration (xiii).

Given Project 2025’s own stated aims, it seems worth talking about this modern-day heresiology and the logics underpinning it. Like Epiphanius, Project 2025 posits an ahistorical and transcendent ideal, arrays the world into rigid binaries, and misrepresents or demonizes those deemed “outsiders” to its own orthodoxy. Consider the foreword, which claims that “the very moral foundations of our society are in peril” (1). Heritage Foundation president Kevin Roberts and his co-authors purport to offer a cure for this moral decline, not unlike the Panarion. But of course, such a narrative presumes an idealized past that was not in decline. Roberts et. al. place this ideal in 1981 with the Reagan Administration, which they claim successfully handled similar “moral and foundational challenges” to those we face today and ought to be the blueprint for the next conservative administration (2-3). Others credit the Reagan administration with contributing to existing and increasing economic disparity, rolling back civil rights gains, and undermining environmental protections. At a minimum, Reagan’s legacy is far more complicated than the idealized renaissance of Founding-era principles we find in Project 2025.

Project 2025, like Epiphanius, presupposes a rigid binary, one drawn across cultural indices. Its authors claim that “America is now divided between two opposing forces: woke revolutionaries and those who believe in the ideals of the American revolution” (19). The former are characterized by their belief in systemic racism; the latter in “America’s history and heroes, its principles and promise, and in everyday Americans and the American way of life” (19).

Note how our authors present vague notions like the “American way of life” as if they are uncontested, as if all Americans agree on what they mean. Disagreement with the authors’ visions of “American life” is seen as a “[threat] from within,” not unlike Epiphanius’ biting beasts (19). Throughout the text, other binaries emerge, many clothed in the language of corruption and moral depravity that ancient heresiologists wield so well. Transgender representation is tantamount to pornography and is blamed for “sexualization of children” (5). The DEI “revolution” is described as a “managerialist left-wing race and gender ideology” that pervades “every aspect of labor policy” (582) and “corrupts” governmental work (584). This language of corruption, moral decline, and existential threat recasts equity as a threatening heresy that must be demolished to preserve the American way of life, a political orthodoxy clearly authored by and primarily for white, cishet, able-bodied men.

Still, why should we care that Project 2025 is modern-day heresiology? I think Averil Cameron said it best when she wrote “orthodoxy is violence.” The production of orthodoxy in literary texts like the Panarion demands erasure or misrepresentation of supposed heresies - decolonial scholars might call this “epistemicide.” But Cameron also speaks of the state violence involved in enforcing orthodoxy. The Christianized Roman empire coerced conformity, silenced dissent, and persecuted religious minorities, including other Christians. Like ancient heresiologies, Project 2025 demonizes and misrepresents those it views as outsiders, here in service of a narrow political orthodoxy about the “American way of life”: an orthodoxy they present as self-evident and ideal, despite the fact that a majority of Americans view Project 2025 unfavorably. As far as any physical or state violence that may arise out of its implementation? We need only turn to Kevin Roberts’ own words: “...we are in the process of the second American Revolution, which will remain bloodless if the left allows it to be.”

Public Writing and a Global Antiquity

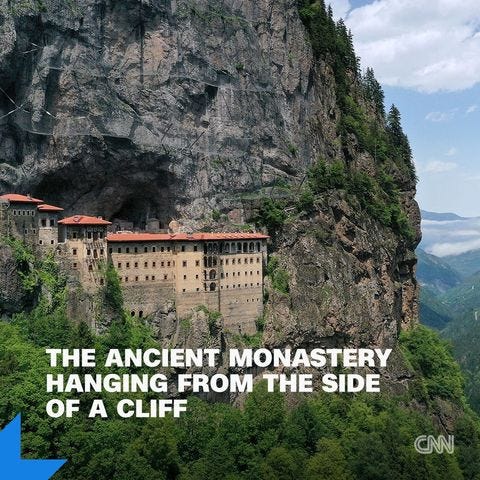

Frescoes, cliffs, and early Christianity—oh my! CNN’s Joe Yogerst spotlights Sümela, a 4th-century CE monastery in Turkey. Tourists and pilgrims alike flock to the site on the Black Sea, once a popular religious site with early Christians and Muslims.

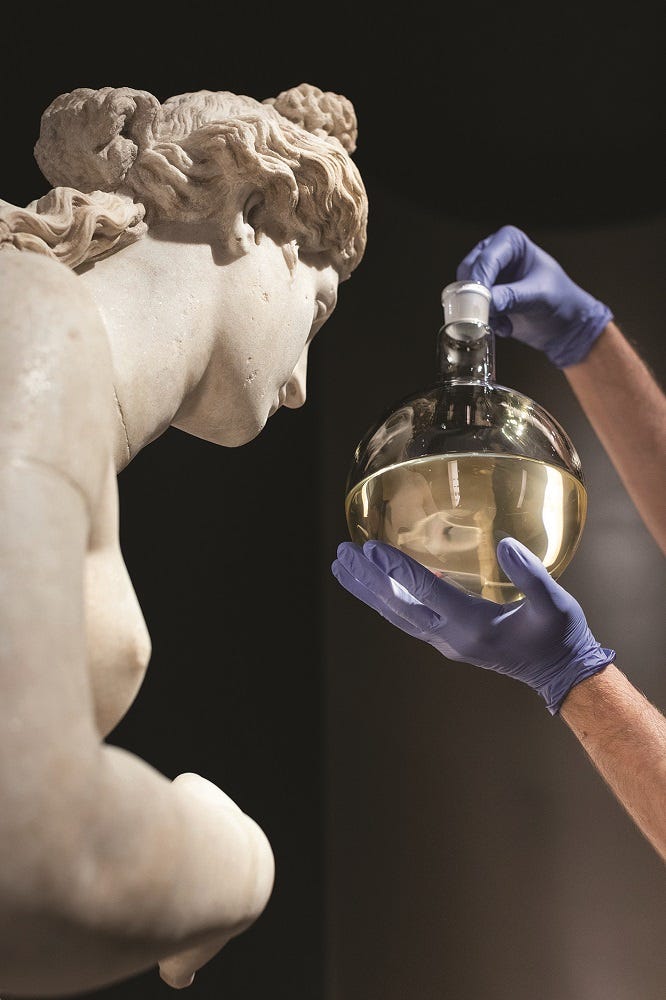

And over at McSweeney’s, travel writer Maggie Downs discusses her journey with the sensory experience of ancient and modern Greece. As she notes, “Back in 2017, the National Archaeological Museum of Greece embarked on a journey to revive the scents of antiquity. Working with the Greek cosmetics brand Korres, they delved into the universe of experimental archaeology…” This was a fab exhibit called “The Scent of Antiquity Reborn,” which used the Linear B tablets to reconstruct the ancient scent called Rose of Aphrodite.

In a time when it feels like a new cannabis product emerges every other week, it’s nice to look back on history and think, I wonder what people did back in the day to take the edge off. Archaeologists working at the pre-Columbian site of El Baúl at Cotzumalhuapa in Guatemala have a bananas answer: drinking tobacco. Researcher Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos and his team unearthed ceramic vessels with traces of nicotine inside. Liquid tobacco, NatGeo’s Anna Thorpe reports, is “highly toxic and can be lethal. It was likely used to induce visions or divinatory trances as part of a controlled ceremonial rite and to minimize pain for humans sacrificed to the gods.”

Kids may say the darndest things, but, as the saying goes, actions speak louder than words. A four-year-old kiddo visiting the Hecht Museum in Haifa, Israel, smashed a Bronze-Age wine jar in a barrier-free display. Not to worry, though—the museum’s conservators came to the rescue, and fixed that puppy right up. It’s now back on display.

Additionally, ancient historian Samuele Rocca has an interesting new, open access article on “A Jewish Gladiator at Pompeii: Reassessing the Evidence" which reconsiders palm tree iconography on a bronze gladiatorial helmet from the site compared with the Iudaea capta coins minted after the Jewish Wars.

As we discussed two weeks ago, looters have raided tens of thousands of artifacts from Sudan’s National Museum in Khartoum. Now, The Conversation has spoken with archaeologist Mohamed Albdri Sliman Bashir, who highlighted the importance of the museum’s collections for future generations.

Cultural collections serve as an anchor for a society’s identity. They embody the shared memory of a community and foster a sense of belonging and continuity with the past. Losing this not only undermines our understanding of who we are, but also hinders the transmission of knowledge and cultural values to our descendants. And their role in the world.

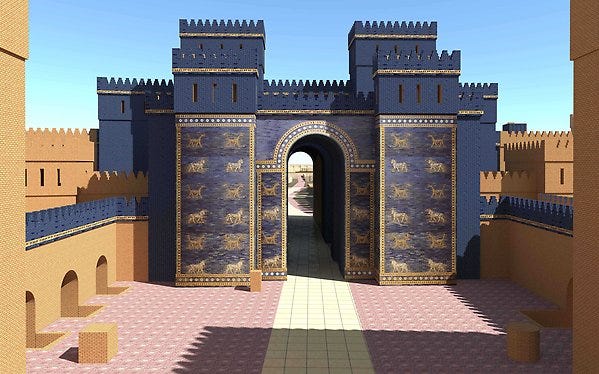

Sometimes I stare at my computer screen and wish I could see a digital reconstruction of ancient Babylon, created with architectural and GIS software and supported by material evidence and ancient texts. The Urban Mind Project at Uppsala University and the Excellence Cluster Topoi at Freie Universität Berlin have granted my wish. Preliminary maps and materials are now available, with more to come!

What happened to the people of Rapanui? For a long time, theories held that the residents of this Pacific island, also known as Easter Island, used up every last resource to build their famous stone status, called moai. These actions led to “ecocide,” which caused a population crash. Now, archaeogeneticists argue that a crash never happened, according to a new study led by Bárbara Sousa da Mota of the University of Lausanne.

For the lactose-tolerant among our readership, The Guardian reports on a cheesemaking revival in Britain. Artisanal cheeses, James Tapper writes, experienced a mass extinction in the postwar period due to a turn towards industrialization. I have personally never thought about terroir as it pertains to British cheese, but at PI we support regionalism!

Cheese was traditionally a way for farmers to preserve leftover milk, especially for the winter months. Britain once had thousands of farmhouse cheeses, but they dwindled first when the acts of enclosure pushed smallholders off the land, then when the Industrial Revolution encouraged producers to ditch long-maturing cheeses in favour of quick ones.

Finally, over at Everyday Orientalism, ancient religions and slavery scholar Chance Bonar has an important post on the the myth that the name “Palestine” was a Roman invention. As Bonar notes:

While the Roman Empire undoubtedly deployed the name Palestine (and Syria) in order to suppress provincial Jewish subjects, this does not mean that they invented the term, nor that other Mediterranean people did not use the term Palestine to describe a broad range of inhabitants, cities, and regions of the coastal Levant. The term Palestine has been used in writing since at least the 12th century BCE and continues to be a term used by scholars in classics, ancient history, and biblical studies to denote a multicultural and multireligious region.

In Memoriam: Peter Green by Professor Emeritus John Finamore

On Monday September 16, 2024 in the early morning, Peter Green died at the age of 99, just three months before his 100th birthday. Peter was a remarkable man, an incredible scholar, and my dear friend. Peter was born in England, served in the intelligence corps in World War II, and studied at Cambridge. After the war, in England he was a journalist and author of historical fiction. He lived with his family on Lesbos in Greece in the 1960s, and eventually took a professorship at the University of Texas in Austin in 1971. After retirement, Peter came to Iowa City, where his wife Carin taught in the Classics Department. Peter taught courses for the Departments of History and of Classics, and became the editor of Syllecta Classica, the journal of the Iowa Classics Department.

Requiescat in pace, Peter.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Polis Vol. 41, No. 3 (2024)

Journal of Indian Philosophy Vol. 52, No. 4 (2024)

AION (filol.) Vol. 45, No. 1 (2023)

Histos Vol. 18 (2024) #openaccess

Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences Vol. 79, No. 4 (2024) Re-Writing Pandemic Histories

Phronesis Vol. 69, No. 4 (2024)

Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology Vol. 7 (2024) #openaccess Epigraphy in Judah

American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 128, No. 4 (2024)

Novum Testamentum Vol. 66, No. 4 (2024)

Greek and Roman Musical Studies Vol. 12 No. 2 (2024)

Digital Scholarship in the Humanities Vol. 39, No. 3 (2024) NB Roxana Beatriz Martínez Nieto & Monika Dabrowska “Ancient classical theatre from the digital humanities: a systematic review 2010–21”

Journal of Late Antique, Islamic and Byzantine Studies Vol. 3, No. 1-2 (2024) : Reconstructing Cross-Craft, Inter-Industry, and Multicraft Relations in the Late Antique Mediterranean

Antiquity Vol. 98, No. 400 (2024)

Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies Vol.66, No. 2 (2023) Domestic violence and vulnerability in the Roman world: setting the scene

Frammenti sulla Scena (online) Vol. 4 (2023) #openaccess

Gnosis Vol. 9 No. 2 (2024) Manichaica-Judaica-Gnostica 1: Polemics, Geographies, and Ethics

Journal of Early Christian Studies Vol. 32, No. 3 (2024) NB Sabrina Inowlocki “From Text to Relics: The Emergence of the Scribe-Martyr in Late Antique Christianity (Fourth Century–Seventh Century)”

Numen Vol. 71, No. 5-6 (2024)

Exhibitions, Events, and Workshops

At the Getty Center in Los Angeles now until December 8, 2024 is Lumen: The Art and Science of Light: “Merging past and present, Lumen highlights the ways in which Christian, Jewish and Muslim philosophers, theologians and artists studied light in Medieval times. The exhibition also includes two related installations from contemporary artists.” Also note they will host Rising Signs: The Medieval Science of Astrology (Oct. 1, 2024 - Jan. 5, 2025): “Dig into Medieval astrology with Rising Signs, on view from October 1 through January 5. You’ll see how the beliefs of Europeans in the Middle Ages impacted the varied aspects of their lives, from medicine to farming.”

Please join Yale University’s Council on Latin American & Iberian Studies on Friday, September 27, 2024 from 12 to 1pm ET for Shanti Morell-Hart's lecture "Intelligible Cuisines in the Ancient Maya Lowlands: Plant Residues and Culinary Qualia." Those who can't attend in person are invited to join us via Zoom.

On Monday, October 7th at 5:30pm ET, Deborah Deliyannis will join the Elizabeth Clark Center for Late Ancient Studies and present “The Twelve Apostles in Early Christianity: Orthodoxy and Ambiguity.” This event will take place in Westbrook 0015 and will be available on Zoom for those unable to join us in person. Register for the lecture here.

We’re always looking for our next guest writer! Pitch your best ideas here.

Well, the Rapa Nui collapse is not only about the population decrease but also about the destruction of the island's flora, specifically trees that could be used to build ocean-going vessels. So even if the population did not collapse, it's still not exactly a success story and doesn't really destroy the collapse narrative as the authors are implying.