This week, historian of ancient science Philip Thibodeau discusses eclipse prediction, Thales of Miletus, and what writers got wrong when covering the recent solar eclipse. Then, a new exhibition on Maya peoples, late antiquity specialist Peter Brown reviews a new book on Christianity, mapping mound building in Wisconsin, a new book on the history of the polis, DNA analysis of baobab trees, new ancient world journals from Colin McCaffrey, current museum exhibitions, a workshop on AI, and much more.

When the Sun Disappears: Notes on the Beginnings of A Science by Philip Thibodeau

In this year the Sun was eclipsed totally and the Earth was in darkness so that it was like a dark night and the stars appeared. That was the forenoon of Friday the 29th of Ramadan at Jazirat Ibn 'Umar, when I was young and in the company of my arithmetic teacher. When I saw it I was very much afraid; I held on to him and my heart was strengthened. My teacher was learned about the stars and told me, 'Now you will see that all of this will go away'; and it went quickly. — Ibn al-Athir, al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh [1] on the eclipse of April 11, 1176 (571 AH).

On April 8, 2024, millions of people across North America watched the sun vanish from the sky. The uncanny darkness was accompanied by other unnatural phenomena, such as birds roosting, a sudden chill in the air, and stars shining by day. Experiencing an eclipse is an encounter with the sublime so powerful that even the most jaded observers are apt to cry or shout out. In fact, for most of our species’ history, feelings of the sublime have taken a back seat to panic triggered by the sudden disappearance of one of the most reliable parts of the natural world. Without the awareness of how one cosmic body can block the light of another, an understandable reaction was to see this event as a disturbance in the spirit world or a warning from the gods. That we react to eclipses today with wonder rather than terror is due to our knowing when, where, and why they happen.

The branch of astral science that deals with these things has been nearly three millennia in the making. The oldest clear traces of eclipse study can be found in the Mesopotamian kingdom of Babylon, where, starting in the 8th century BCE, scholar-priests began compiling daily observations of the stars, weather, and other phenomena in what are known as the Astronomical Diaries. They soon noticed that lunar eclipses always take place at least five or six months apart. This observation allowed them to forecast eclipse possibilities – that is, to identify full moons when an eclipse was likely to occur (and did occur, about 40 percent of the time). They also noticed that the five- and six-month intervals formed a repeating pattern that looks like this:

6 6 6 6 6 6 6 5

6 6 6 6 6 6 5

6 6 6 6 6 6 6 5

6 6 6 6 6 6 5

6 6 6 6 6 6 6 5

This pattern – known today as the ‘Saros Cycle’ – was reliable enough that it could be used for predictions. A remarkable cuneiform tablet from the city of Larsa (modern Tell as-Senkereh, about 12 miles east of Uruk) dating to 531 BCE describes how officials there hired a crew of holy drummers ahead of time to drive the coming darkness away from the moon. The drummers left upset:not by the eclipse itself, but by their mistreatment at the hands of the officials. Predictability can drain some of the ominous quality from eclipses by making them appear more routine.

Herodotus in his Histories (1.74) has the Greek sage Thales of Miletus forecast a total solar eclipse, which then occurred on May 28, 585 BCE: “Thales of Miletus proclaimed in advance to the Ionians that this change of day would happen, putting forward a limit during this year in which the transformation actually took place”(1.74.3). In a piece for the New York Times, science reporter William Broad recently claimed that Thales “shook the world” by predicting this event. But did he? This is, after all, the same Herodotus who wrote about fox-sized ants in India that dig up gold. In fact, there is no way that Thales could have predicted this particular “change of day.” Babylonian astral methods were state secrets that did not travel to Israel or Egypt, much less Miletus; even if they did, Thales would have had almost no luck using them. For while solar eclipses also occur after similar five- and six-month intervals, this method generates far fewer ‘hits’ – partial eclipses happen only 25 percent of the time, total or near total events only about 1 percent. It is more plausible that Thales commented after the event on the occasions when solar eclipses occur – around the new moon, say, or near the solstice. It would take only a small leap for Herodotus to present this statement as a genuine prediction.

The key Greek contribution to eclipse theory had instead to do with causation. The double recognition that the moon is an opaque, spherical body that causes the sun to disappear by passing in front of it, and is itself obscured when it passes through the shadow of the earth, was first made by the philosopher Anaxagoras of Clazomenae – a friend of the Athenian statesman Pericles who, like Socrates, was charged with impiety for his speculations. Thinking of the sun and moon as solid spheres would allow later Greek astronomers to estimate the size and distance of the sun and moon. But for an understanding of their relative speeds and motions – information without which there can be no accurate solar eclipse prediction –Greek astronomers were indebted to the Babylonians, whose century-long observation program had no parallel in the ancient Greek world.

Babylonian and Greek contributions are just a part of a broader, global science. In her lucid study Chasing Shadows, Clemency Montelle traces this history even further, explaining how Mesopotamian and Greek astral lore was transmitted to sages in India, who then devised ingenious methods for calculating stellar positions to high levels of precision; and thence to philosophers in the Arab world who made heroic efforts to iron out the inconsistencies in various competing systems. When Isaac Newton published his laws of gravitation, eclipse theory took another great leap, as his equations made it possible for astronomers to calculate exactly where on earth the moon’s shadow will fall. But even today, there remains room for improvement: last-minute calculations led to a slight revision in the path of totality of April’s event.

Even after three millennia, eclipse prediction remains an imperfect science.

[1] IX, p. 138. (quoted by Stephenson 1997, 439)

Abbreviated Bibliography on the History of Eclipse Prediction

Beaulieu, Paul-Alain, and John P. Britton. 1994. “Rituals for an Eclipse Possibility in the 8th Year of Cyrus.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 46: 73–86.

Bowen, Alan. 2002. “The Art of the Commander and Predictive Astronomy.” In, Science and Mathematics in Ancient Greek Culture. C. J. Tuplin and T. E. Rihll, editors. Oxford University Press. 76–111.

Graham, Daniel W. 2013. Science before Socrates. Parmenides, Anaxagoras, and the New Astronomy. Oxford University Press.

Jones, Alexander. 2017. A Portable Cosmos: Revealing the Antikythera Mechanism, Scientific Wonder of the Ancient World. Oxford University Press.

Montel, Clemency. 2011. Chasing Shadows: Mathematics, Astronomy, and the Early History of Eclipse Reckoning. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Popova, Maria. 2017. “The World’s First Celestial Spectator Sport: Astronomer Maria Mitchell’s Stunning Account of the 1869 Total Solar Eclipse.” The Marginalian.

Stephenson, Frederick R. 1997. Historical Eclipses and Earth’s Rotation. Cambridge University Press.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

Public Books has an open call for submissions for their series “Voices of the Campus Protest Movement.” (Stephanie is a contributing editor for PB and can advocate for your story if you want a bigger platform to amplify your voice.) Reach out to us here by June 1, 2024:

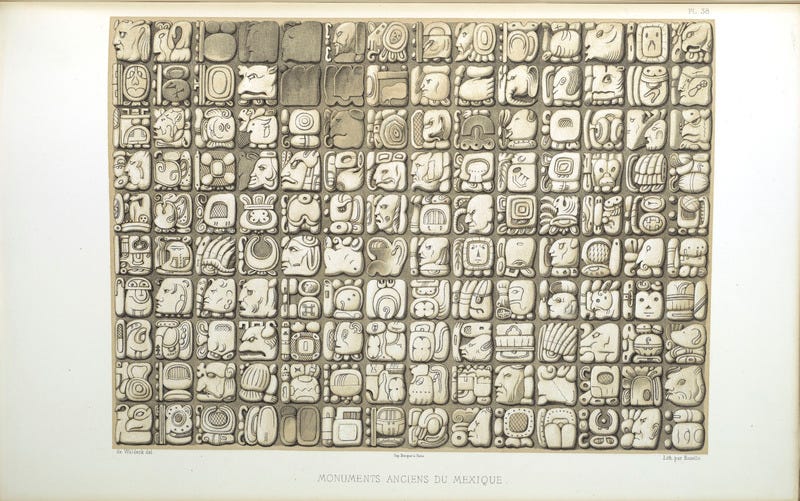

Spanish conquerors and missionaries razed numerous books focused on Mayan hieroglyphics when they invaded Mesoamerica. But a new exhibit about 19th and 20th-century Maya peoples is up at the Wilson Library of University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill that recounts how it was deciphered and ultimately preserved by the Maya. It follows the stories of resistance, struggle, and legacy from Mexico and Central America through the Library’s Stuart Collection and Rare Book Collection.

Over at the NYRB, Peter Brown has a new essay, “The Workings of the Spirit,” which reviews Peter Heather’s new book, Christendom. Brian Sowers’ book translating the poetry of Aelia Eudocia (c. 400-460 CE), In Her Own Words: The Life and Poetry of Aelia Eudocia, is now open access from the CHS. And at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library channel, they have re-upped a great interview with Getatchew Haile, PhD, former Cataloger and Curator Emeritus of HMML’s Ethiopian Manuscripts, who sadly passed in 2021.

The first issue of QTR: A Journal of Trans and Queer Studies in Religion is out now. The open-access journal focuses on the “rich and complex connections between religion, gender, and sexuality.” Talmud expert Max Strassfeld’s fascinating article on the work of John Boswell examines use of the analogy between gays and Jews. Strassfeld critiques Boswell’s work, but underscores his impact:

“[Boswell’s argument that the] origins of homophobia in the West should not be simplistically attributed to early Christianity was groundbreaking. In Boswell’s analysis, early Christianity emerges within the relatively permissive Greco-Roman milieu, and only later (in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) is there a historical shift toward intolerance of homosexuality.”

At the splendid fashion history pod, Articles of Interest, Avery Trufelman explores the history of clerical and religious clothing worn within “Islam, Mormonism, and Judaism, and all of their varying and overlapping commands.”

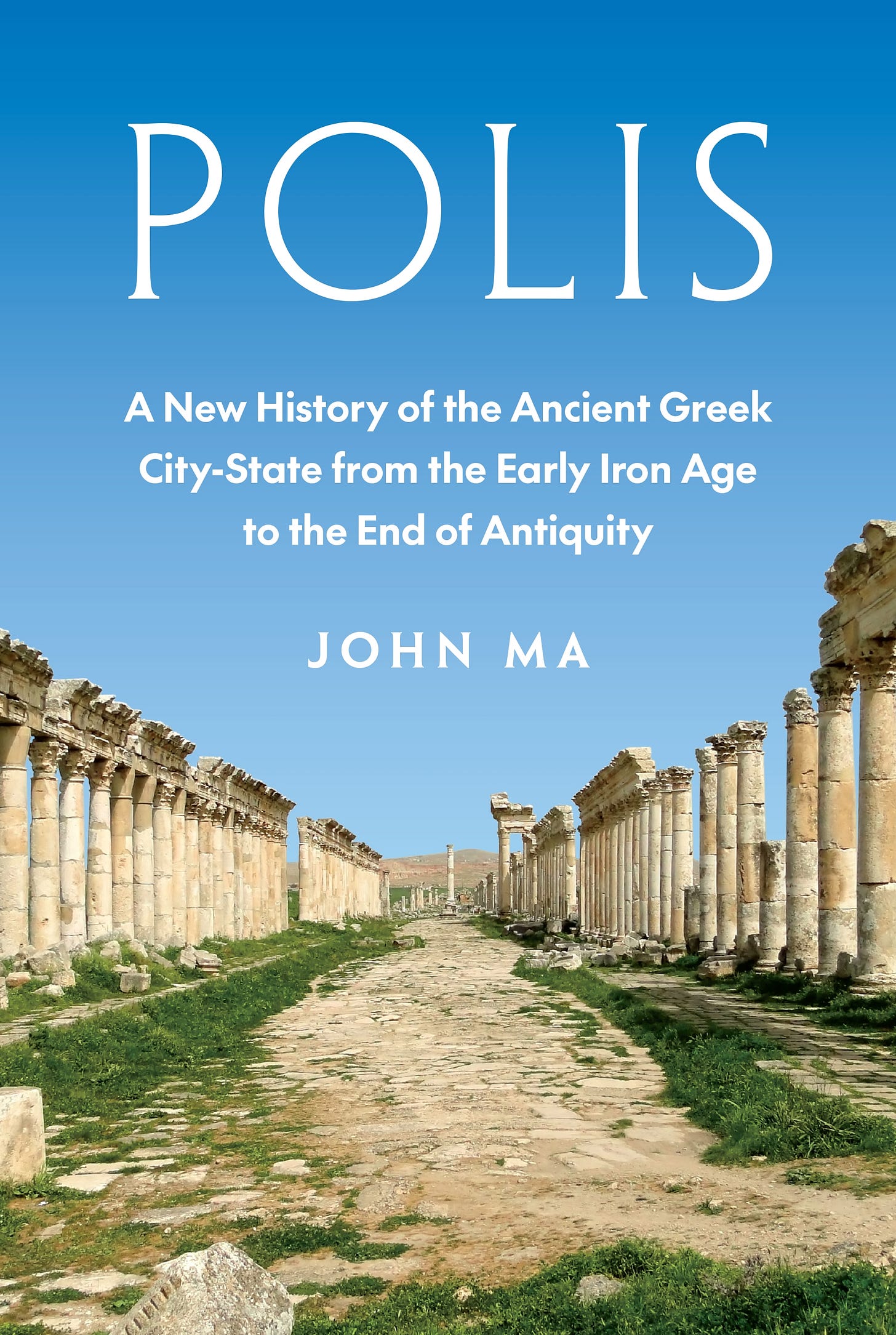

Historian of ancient Greece John Ma has an innovative new book: Polis: A New History of the Ancient Greek City-State from the Early Iron Age to the End of Antiquity. In comments to Pasts Imperfect, Ma noted that Polis was a long book centered around a simple story:

Not that of the city, but of the polis as political form— an Aristotelian story where stateness, law, access to decision-making and institutions are central, and where elections matter. The long arc of polis history ultimately leads to an ‘end of history’, the great convergence around certain norms: constitutional democracy (with concomitant economic redistribution) and autonomy. The processes start in the late fourth century BCE, continuing into the second century BCE. The outcomes prove surprisingly durable, notably because the Roman empire coopts them; hence it's not excessive to call Greek cities under the Roman empire "democratic" (in some way).

Ma traces this achievement, but also pulls no punches in confronting the entanglement of the “good polis” (civic, democratic, egalitarian, autonomous) and “bad polis” (enslaving, misogynistic, patriarchal, domination-obsessed, selfishly self-satisfied). It is out June 4, 2024.

Science reporter Carolyn Y. Johnson at the Washington Post shares exciting news about Parsons Island in the Chesapeake Bay: people were in the Americas much earlier than previously believed. Coastal geologist Darrin Lowery posits that stone tools dating from 22,000 years ago may have belonged to the ancestors of local Indigenous peoples.

If Lowery is right, Parsons Island could rewrite American prehistory, opening up a host of new puzzles: How did those people get here? How many waves of early migration were there? And are these mysterious people the ancestors of Native Americans?

Wisconsin! Mounds! What’s not to like? Frank Vaisvilas at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reports on a recent self-published book for a lay audience about the 20,000 mounds found in Wisconsin. Written by archaeologist Kurt Sampson and ecologist William Volkert, this book discusses the region’s long history and incorporates voices from the Ho-Chunk Nation.

Oh yeah, snail juice. Lest we forget about the ancient Mediterranean murex, which made the Tyrian purple that had rich folks paying out the nose for a crimson toga, a big lump of dyestuff has been excavated from a bathhouse in Roman Carlisle in the UK. One imagines it must have been a bright (and costly) pop of color for ancient Northern Europeans, who were probably suffering from seasonal affective disorder real bad. In addition, Hyperallergic reports on the return of a Ptolemaic statue by the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) back to Libya and IMEMC notes that Munir Anastas, the Ambassador of Palestine to UNESCO, “strongly denounced Israel’s ongoing actions of stealing valuable artifacts and demolishing cultural heritage sites during its violent conflict in the Gaza Strip.”

Also, from the British Isles is a very old Irish stone dug up by a geography teacher in his Coventry garden. Graham Senior, age 55, was weeding a flowerbed when he came across a rock with some funny markings on it—turns out it’s a 1,600-year-old inscription in ogham, an early medieval Irish alphabet. You should open the article link just to see the photograph of Mr. Senior with the artifact on display at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum.

This is a bit more ancient than we usually go, but screw that, because baobab trees are awesome. Helen Briggs at the BBC reports that baobabs appeared in Madagascar 21 million years ago. Dr. Ilia Leitch of the Royal Botanic Gardens told the BBC that the new data found via DNA analysis will allow scientists to increase their efforts towards conservation. I mean, these trees can live for thousands of years. We are not worthy, we are not worthy.

And: well done, Miami Herald editor. I just love this headline: 2,000-year-old toilet bowl found in Roman ruins — revealing ancient health issue. The chamber pot was found in Viminacium, Serbia and dates to the 3rdC CE. Reader, I clicked.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Near Eastern Archaeology Vol. 87, No. 2 (2024) NB Diane Harris Cline, et al. “Dawn and Descent: Social Network Analysis and the ASOR Family Trees”

International Journal of the Classical Tradition Vol. 31, No. 2 (2024)

Early Science and Medicine Vol. 29, No.2 (2024)

Mnemosyne Vol. 77, No. 3 (2024) NB Chrysanthos S. Chrysanthou, “Group Minds in Ancient Narrative: Herodian’s History of the Roman Empire as a Case Study”

Erudition and the Republic of Letters Vol. 9, No. 2 (2024) NB Derrick Mosley, “The Origins and Sources of Newton’s Classical Scholia”

Vigiliae Christianae Vol. 78, No. 3 (2024)

Ramus Vol. 52, No. 2 (2023) The journal’s final issue. NB Mathias Hanses, "Vitruvian Man and Virtuous Woman: A Retrospective on the Homo bene figuratus through Leonardo da Vinci and Harmonia Rosales."

Ordia Prima Vol. 2 (2024) #openaccess Gramáticos latinos fragmentarios

Digital Classics Online Vol. 10, No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut Jahresbericht 2023 #openaccess

Vivarium Vol. 62, No. 2 (2024)

Classical World Vol. 117, No. 3(2024)

Frankokratia Vol. 5, No.1 (2024)

Journal of Greek Linguistics Vol. 24, No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

Early China Vol. 46 (2023)

Classica et Mediaevalia No. 1 (2024) #openaccess Unity and diversity in ancient Greece: thoughts on the occasion of the 2500th anniversary of the Battle of Plataiai

Studies in Ancient Art and Civilisation Vol. 27 (2023)

postmedieval Vol. 15, No. 1 (2024)

Cuadernos de Arqueología de la Universidad de Navarra Vol. 32 (2024) #openaccess

Historikà Vol. 13 (2023) #openaccess

Gephyra Vol. 27 (2024) #openaccess In Memoriam Stephen Mitchel

Peritia Vol. 34 (2023)

Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies Vol. 12, No. 2 (2024)

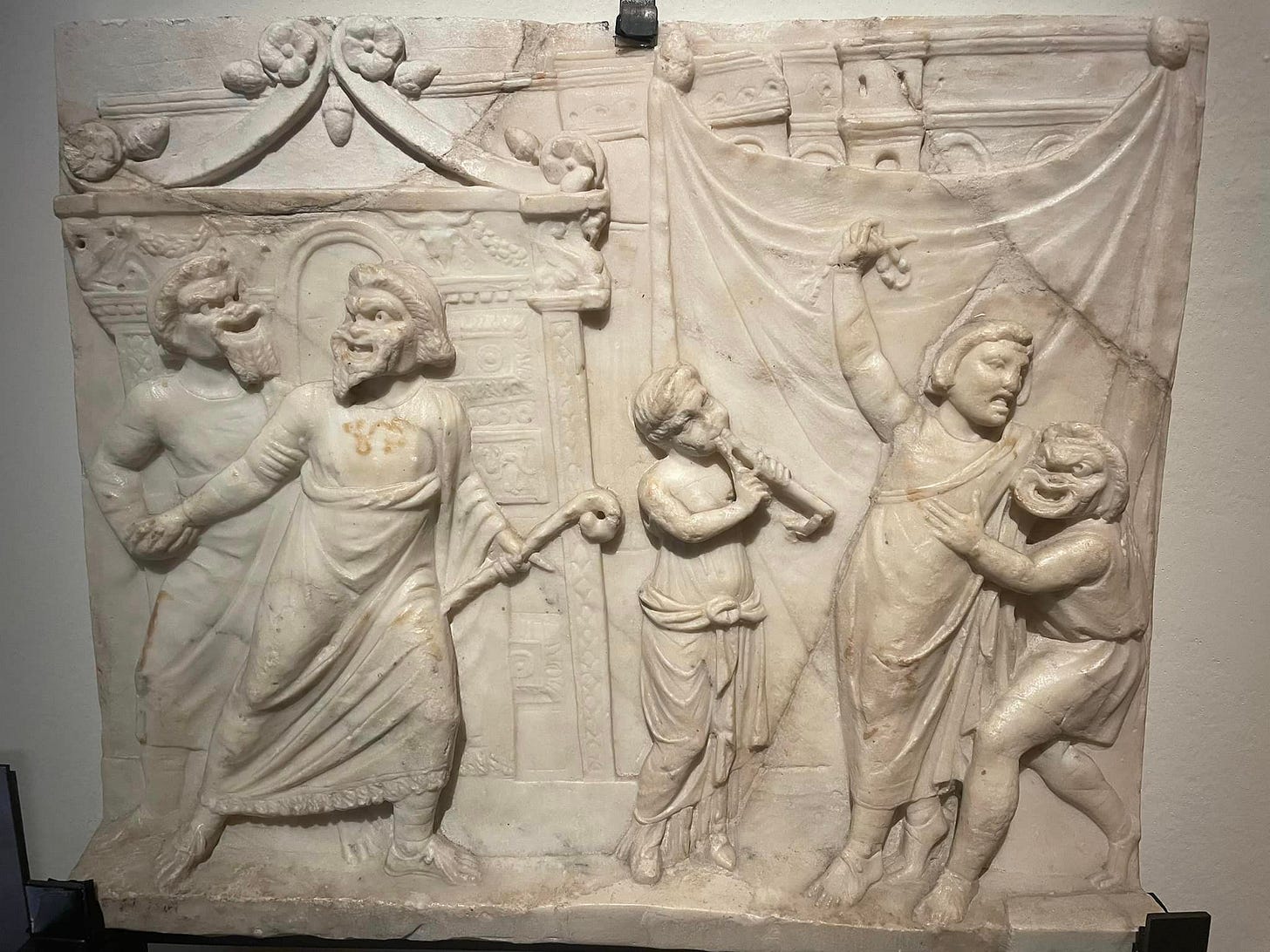

Exhibitions, Events, and Workshops

The Museo dell'Ara Pacis is hosting a new exhibition on ancient theater, Teatro. Autori, attori e pubblico nell'Antica Roma, from May 21 until November 3, 2024. At the Cleveland Museum of Art, on now until September 1, 2024, is “Carpets and Canopies in Mughal India” and at the Palace Museum in Beijing, China is the “The Glory of Ancient Persia.” Nota Bene that the AJA has an updated list of museum exhibits.

On Monday, June 3 and Tuesday, June 4, 2024, the University of Bristol Faculty of Arts, Institute of Greece, Rome, and the Classical Tradition, Bristol Digital Game Lab, and Centre for Creative Technologies will host “24 presentations from academics and industry professionals working at the intersection of Classics, Gaming, and Extended Reality, as well as numerous demos and collaborative play sessions.” The conference will be held in the Humanities Research Space, and also on Zoom. Signup at the Bristol Digital Game Lab's TicketTailor page.

The Women’s Classical Caucus is hosting an online workshop, “Publishing a Journal Article: A WCC Publishing Series Event on June 6, 2024 11:00 AM - 12:30 PM (ET).

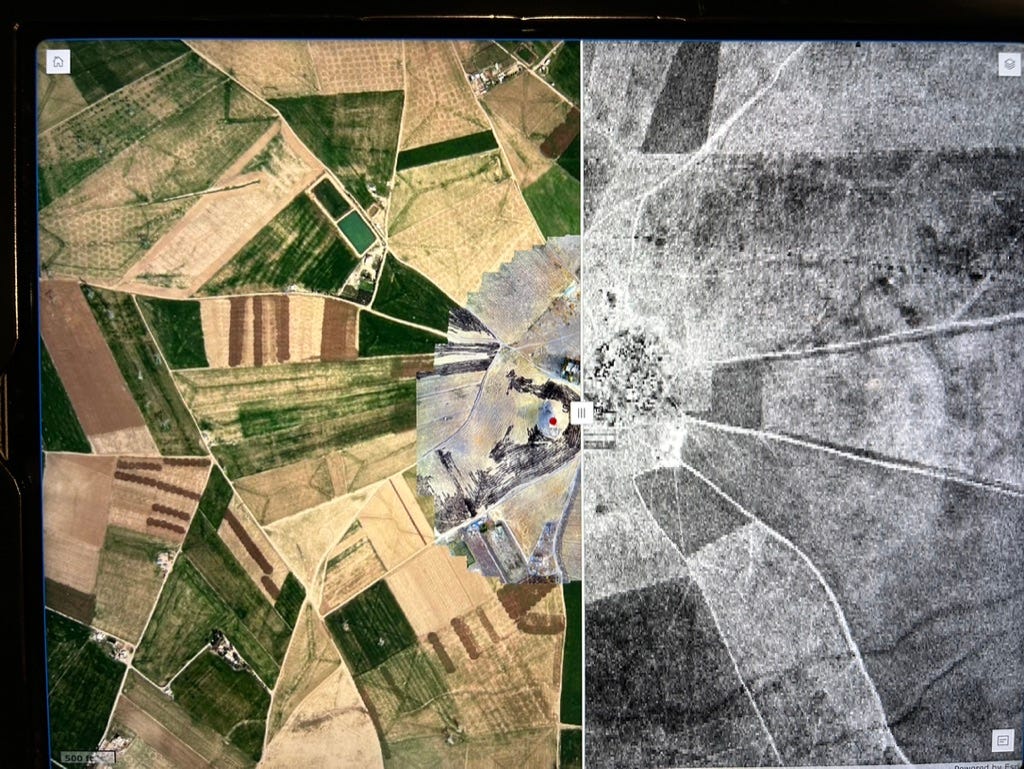

In Chicago, the ISAC Museum Satellite Exhibit: “Fifty-Cent Men”: How The Gold Reserve Act Altered The Business Of Archaeology” is on from May 6, 2024-May 2025. Additionally, “Pioneers Of The Sky: Aerial Archaeology And The Black Desert” is on now August 18, 2024. It tells a fascinating story of aerial photography, balloons, cold war maps, and the history of archaeology in Jordan.

On Monday, June 3, 2024, 4.30-6pm UK time on Zoom, the editors of the recently published volume, Greek Tragedy and the Middle East: Chasing the myth (2024), Pauline Donizeau, Yassaman Khajehi, and Daniela Potenza, will deliver a seminar in the ‘Out of the Shadows of Empire’ series. “Their presentation will be based on their new book, which explores the interculturality of adaptations of Greek tragedy in the Middle East from the turn of the 20th century to the present, spanning Arabic, Iranian, and Turkish contexts. Offering the first wide-ranging approach to Middle Eastern receptions of Greek tragedy, they present a timely analysis of its entanglement and disentanglement with colonialism and cultural imperialism.” Attendance is free and open to all. Register here.

The Alan Turing Institute special interest group in Humanities Data Science is hosting an event in Oxford, “The Impact of Generative AI on the Digital Humanities: Disruption in Research and Education” will be held on June 21, 2024. The event will be held in the Weston Library lecture theatre, with lunch in Blackwell Hall. It will also be streamed online. “Attendees can expect a deep dive into applications of generative AI, its challenges and implications for academia and beyond, highlighting the need for responsible and creative integration of these technologies.” Note: Online registration and in-person registration.