Pasts Imperfect (5.29.25)

Gamifying the Past, Louse-y Wool, Neanderthal Fingerprints, the Women of Pompeii, Classicism and Other Phobias & Much More

This week, archaeogaming expert and ancient history podcaster Lexie Henning discusses gamifying history and the future of humanities teaching. Then, a note from XBox President Sarah Bond, ancient Bhutanese woodcarvings and AI, Hannibal’s elephants and his legacy, louse-borne relapsing fever and the ancient wool trade, new books on the women of Pompeii and the lacking concept of “classicism,” a Neanderthal fingerprint from Spain, ancient world journals, and much more.

Gamifying History is the Future of Humanities and STEM by Lexie Henning

Wait, there’s real history in video games? Yes! Canadian gaming company Ubisoft, in particular, is known for trying to cram real ancient history and archaeology into their games. Their recent games: Assassin’s Creed Origins (2017), Odyssey (2018), & Valhalla (2020) are set in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Viking Age England respectively. These games allow us (as players) to walk through a pyramid, sail across the Aegean, or storm a castle fighting Alfred the Great. But the main purpose of a game is entertainment, which means we need to fill in the blanks in the classroom!

With declines in education funding and ballooning costs of operations, universities everywhere are forced to decide where to allocate their precious resources. The current line of thinking is that humanities programs aren’t as valuable or profitable for long term growth and innovation. It’s no secret that US students regularly perform poorly on math and science exams, lagging far behind the majority of developed nations. But in our haste to address this deficit and become more competitive, our humanities programs are suffering in order to maintain STEM programs.

Studying the ancient world also faces a major relevancy problem. How do we make the study of peoples and cultures thousands of years old relevant in modern classrooms? That’s the $1.5 trillion dollar question. And while trying to answer that question, Classics departments all over are meanwhile being dissolved, merged, or are desperately clinging to life while being slowly squeezed to death by the unending hydra of budget cuts.

Despite post-pandemic fluctuations, tech jobs are still projected to grow. According to the Computing Technology Industry Association’s State of the Tech Workforce report, tech job growth was projected to go from 6 million in 2024 to 7.1 million in 2034. Additionally, according to research from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, computer/ IT jobs are expected to grow with a projected 356,700 jobs annually. This compared to the (melting) glacial academic job market, which has about 52 to 66 assistant level tenure track Classics job listings per year. However, the notion that STEM alone is the key to future success is wrong. While STEM fields may produce individuals with specialized skill sets, critical thinking, discourse, and communication skills are much more important.

On the more profitable side of practical humanities applications, the ever expanding, multi-billion dollar video games industry employs humanities majors, including classicists. Assassin’s Creed, an extremely popular and successful series relies on animators and programmers, but having a strong historical and narrative team is essential. Creating a simulated ancient world with nothing to do would be boring. A classicist can learn to code, but their most valuable contributions are research, knowledge of foreign and ancient languages, and expertise in using accurate information to build historically based fictional universes. Other popular historical games include Sid Meier’s Civilization, Ghost of Tsushima and God of War, which are successful thanks to the contributions of scholars like Andrew Johnson.

Ubisoft’s 2017 title, Assassin’s Creed Origins, is set in Ptolemaic Egypt. By employing a team of dedicated historians (like Perrine Poiron & Maxime Durand), Ubisoft created a game that would more authentically reflect the Hellenistic elements of the time period. They took it one step further, and developed their Discovery Tour mode. This mode is separate from the main game and can be used to walk around a reconstructed ancient world and learn about Egypt. In 2018, Christian Casey presented a paper on how the game can be used for serious scholarship. In fact, it’s now become so popular that educators have now started using it to teach about the ancient world.

However, many scholars still argue that games shouldn’t be used to teach, as they often portray history inaccurately. In her recent edited volume Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games, Jane Draycott poses fundamental questions about who gets to decide what is considered historically accurate or authentic and whether game developers should strive to make accurate games. She posits that large AAA studios like Ubisoft invest so much money on their games that they can’t afford to alienate large sections of their customer base by discarding historical accuracy in favour of a more fantastical approach. Meanwhile, smaller independent studios have much lower costs, which allows them to take a more flexible approach to history. This consideration surely affects which games make it into classrooms, but studying Classics in non-Classical material has recently emerged as a topic at the forefront of gaming research in Classics, as identified at a conference hosted in June 2024 at the University of Bristol.

This fast-growing subfield of archaeology we call “archaeogaming” integrates the methods of archaeological discovery into the synthetic environment of video games. Accuracy & authenticity aside, this offers a solution to presenting ancient content to modern audiences, allowing people to learn and teach about the ancient world by playing a historical video game. We need to integrate technology and ancient materials to bridge the engagement gap. But implementing technology in the classroom simply because it looks fun and engaging would be a mistake.

The key to good pedagogy is in the intentional effort of using the tech as a tool to achieve a specific objective. So, rather than only using Assassin’s Creed Origins to teach students about the pyramids, an educator should first teach their students about the pyramids using traditional methods and then use the game as supplemental material to help reinforce their knowledge and encourage mastery of the subject. Done correctly, archaeogaming bridges the gap between past and present through popular digital engagement and can create sustained interest in the ancient world, on its own merits—all while opening the door for collaboration, rather than competition with technology.

Humanities using technology is part of STEM education. In 2019, researchers at Dallas’ Southern Methodist University received a National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant to study how Minecraft can inspire game-based learning. While that particular study focused on ways to teach students computational learning, there are arguments to be made for computational skills being necessary for archaeogaming as well. The humanities rarely attempt to compete for science funding even when using technological methods for education. That needs to change if we are to survive in this hypercompetitive, technological world.

A Note From XBox President Sarah Bond to the readers of Pasts Imperfect

“To play is fundamentally human—it's integral to how we learn, come together, and share our stories. Games like hide and seek or tag have been with humanity since the dawn of time. They create camaraderie, develop skills, spark imagination, and inspire problem solving. Video games build on this deep-rooted tradition but add something unprecedented: the ability to transport us into other worlds with an intensity and fidelity that no other medium can match. With interactive storytelling, compelling imagery, and real-time social connectivity, video games don't just entertain—they educate, empathize, and preserve. They allow us to walk through ancient cities, confront historical injustices, relive forgotten moments, and see through the eyes of people we might never otherwise understand. They offer us a uniquely powerful way to engage with history—not as passive observers, but as active participants. That’s more than play. That’s cultural memory, empathy, and learning—brought to life.”

As y’all can see, having a much cooler name doppelgänger is daunting. We are thankful she took the time to speak to PI. Do take a moment to listen to the fabulous talk she gave at SXSW on the power of games—and consider gamifying your syllabi a bit in the fall.

Global Antiquity and Public Humanities

On May 10, 2025, the Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia opened. For their display, Bhutan has chosen Ancient Future: Bridging Bhutan’s Tradition and Innovation. Their exhibit pairs traditional Bhutanese woodcarvings—done by artisans Sangay Thsering and Yeshi Gyeltshen, per BIG—on one side with a simultaneous AI interpretation of their ancient designs on the other. The exhibition is arguing for the use of AI as a future form of cultural preservation. While we remain skeptical, it is at least worth a look at the mini-documentary they have made to accompany the show.

Look, we want you to be historically entertained. And at the Hollywood Reporter, they note that Dev Patel has signed on to direct and star in The Peasant, “An adrenalized revenge thriller, the project is being described as having shades of Braveheart and John Wick as well as notes of King Arthur as it mashes up medieval knights with feudal India.” It is set in the 1300s CE and focuses on “a shepherd who embarks on a rage-fueled campaign against a group of mercenary knights who ransacked his community, revealing himself to be more than he seems.” You had me at rage-fueled peasant revolt.

In the London Review of Books, Michael Kulikowski reviews Simon Hornblower’s new book on Hannibal and Scipio: Parallel Lives. Kulikowski concludes with a line I now wish emblazoned on a shirt for the day I teach the end of the Second Punic war:

Hannibal had no offspring, as far as we know, and no political legacy to speak of, but he is the one who lives on in popular memory. Blame the elephants. 🐘

And in the New York Review of Books, Ingrid D. Rowland looks at Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture by reviewing Indra Kagis McEwen’s All the King’s Horses: Vitruvius in an Age of Princes. McEwen casts Vitruvius as a Renaissance era manual on building structures as well as empires.

Over at the New Books Network, Monika Amsler discusses her new book, The Babylonian Talmud and Late Antique Book Culture. The book is available open access (free books are my love language) from Cambridge University Press.

You know that at PI that we’re all about textiles, so reading this headline in Nature made me jump: “This ancient pathogen became deadlier when humans started wearing wool.” What the heck! Around 3000 BCE, when wearing cozy wool sweaters was the new fad in clothing technology across Eurasia and Europe, a bacterium called Borrelia recurrentis spread through body lice. The louse eggs also found wool very cozy and began disseminating louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF). These were the sacrifices our ancestors made so we could wear clothes. The authors “sequenced four ancient B. recurrentis genomes from remains in the UK, the oldest of which dates to 2300 to 2100 years ago.” You can read the whole article here.

And Ari Daniel at NPR reports on an ancient fish that gave us humans our sensitive teeth. Check out the illustration: she’s a baddie.

Readers in Portland, OR: I know you’ve always wanted to know what ancient Roman food tastes like. Chef Alexander Caraway has all the culinary answers in their new pop-up, Salona.

Caraway will be serving dishes like pork belly with a red wine reduction over spelt porridge and chicken wings that are crusted with barley, fried, and served with a grape must. There’s also a salad with oenogarum (fish sauce, red wine, and olive oil), which Caraway describes as, “The original salad dressing. Like the first one.

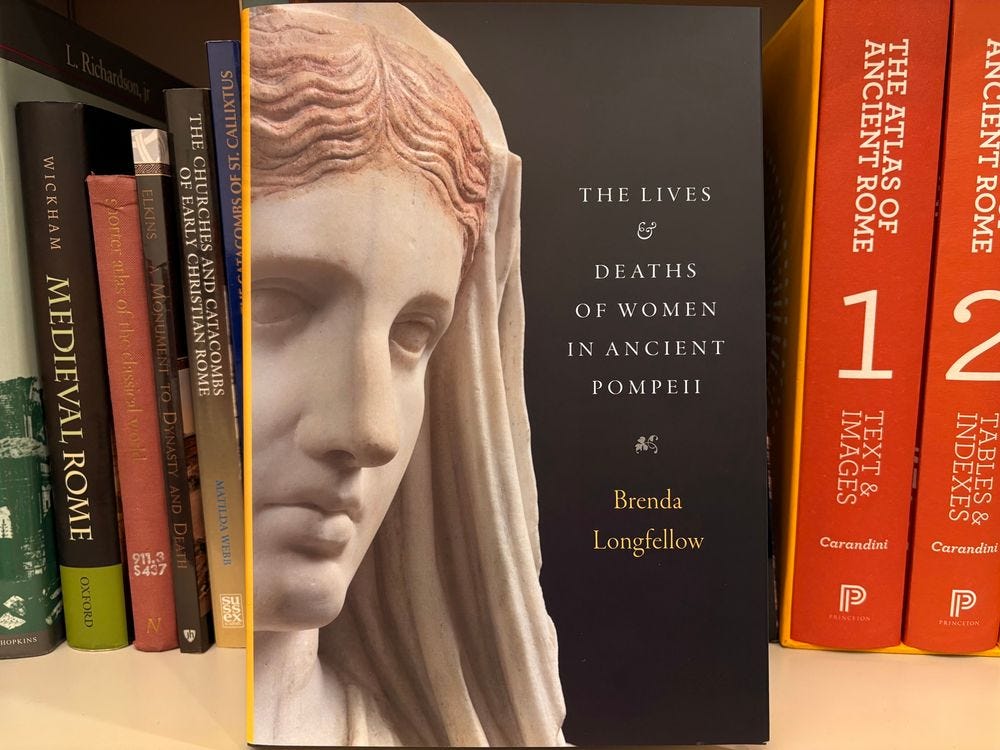

On July 8, 2025, Pompeii art historian Brenda Longfellow has a new book out on The Lives & Deaths of Women in Ancient Pompeii. The book dovetails nicely with the current exhibition at Pompeii: “Essere donna nell’antica Pompei / Being a Woman in Ancient Pompeii,” on display until January 26, 2026. In addition, Dan-el Padilla Peralta’s new book, Classicism and Other Phobias, will be out on July 15, 2025.

A late antique chained ascetic found near Jerusalem was found to be a woman; three ancient Egyptian tombs dating to the New Kingdom (1550–1070 BCE.) were found on the West Bank of Luxor; and the Wisconsin Dugout Canoe Survey Project has now catalogued “two of the ten oldest dugouts [i.e., canoes] found in eastern North America, ranging between 4,000 and 5,000 years old.” These impressive dugouts are then roughly contemporaneous with the Step Pyramid of Djoser, considered the oldest major ancient Egyptian pyramid.

Ancient military historian Bret Devereaux has published a thoroughly enjoyable analysis of the “The Logistics of Road War in the Wasteland,” analyzing the warfare in the Mad Max universe. And Gregory Aldrete has a new Roman daily life video out at After Skool that pairs well with his Daily Life in the Roman City: Rome, Pompeii, and Ostia. I use this as my textbook (Sarah here!) to teach my Roman civ courses and it works really well to teach topically rather than chronologically.

Roses are red

Ancient pigments could be too

They found the world’s oldest fingerprint dipped in some

Yielding a Neanderthal breakthrough

Antiquity Journal Issues (by yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Antiquité Tardive Vol. 32 (2024) Langues, langages et communication dans le monde tardo-antique

Classical Receptions Journal Vol. 17, No. 2 (2025)

The Classical Review Vol. 75, No. 1 (2025) NB Gregory Crane, Alison Babeu & Farnoosh Shamsian “Greek, Latin, and Augmented Intelligence: The Other AI”

Classical World Vol. 118, No. 3 (2025)

eisodos No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies Vol. 65 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Heródoto Vol. 9, No. 2 (2024) À margem da história dos Estudos Clássicos

Historiae Vol. 22 (2025) #openaccess

International Journal of the Classical Tradition Vol. 32, No. 2 (2025) NB Anastasia Pantazopoulou, “What Does Katniss Have to Do with Helen? Tracing the Euripidean Model in Gary Ross’s The Hunger Games (2012)”

Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology Vol. 12 No.1 (2025) #openaccess

Journal of Greek Linguistics Vol. 25, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess Information structure in Greek: interface and comparative studies,

PHASIS Greek and Roman Studies Vol. 27 (2024) #openaccess

Apeiron Vol. 58, No. 2 (2025)

Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy Vol. 64 (2025)

Oriens Vol. 52, Nos. 3-4 (2024) NB Mikolaj Domaradzki, “Ventriloquizing Islamic Neoplatonism through Presocratic Thinkers”

Polis Vol. 42, No. 2 (2025) NB Adam Waggoner, “Aristotle and the Binds of Natural Slavery”

Sophia Vol. 64, No. 2 (2025)

Aethiopica Vol. 27 (2024) #openaccess

Altorientalische Forschungen Vol. 52, No. 1 (2025)

Bulletin of the American Society of Overseas Research (BASOR) Vol. 393 (2025)

Iranica Antiqua Vol. 59 (2024)

Iran and the Caucasus Vol. 29, No. 2 (2025)

Iranian Studies Vol. 58 , No. 1 (2025)

Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde Vol. 152, No. 1 (2025)

Cambridge Archaeological Journal Vol. 35 , No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

History of Religions Vol. 64, No. 4 (2025)

The Journal of Religion Vol. 105, No. 2 (2025)

Liber Annuus Vol. 74 (2024)

Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum= Journal of Ancient Christianity Vol. 29, No. 1 (2025) NB Austin Steen, “Cyril of Alexandria and the Apis Bull”

Frankokratia Vol. 6, No. 1 (2025) NB Austin Steen, “Cyril of Alexandria and the Apis Bull”

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Vol. 9, No. 3 (2025) #openaccess Mappings

Quaerendo Vol. 55, No. 2 (2025) NB Rosamond McKitterick, “Text and Paratext in the Early Medieval Book”

Events, Workshops, and Exhibitions

From June 13-14, 2025, King’s College London will host in person and online: “Bridges between Parallel Paths: Arabic-Islamic and Latin Christian Medieval Philosophies,” a conference bringing together scholars of the Islamic-Arabic and Latin-Christian philosophical traditions of the Middle Ages.

From June 26-27, 2025, the American Academy in Rome and the Academia Vivarium Novum will host “New Insights on Roman Economy and Society,” a conference that looks at the Roman economy through issues like “free labor, entrepreneurship for enslaved people and women, legal fiction, and the social realities of life as experienced from the late Roman Republic to the fall of the Roman Empire.” You can go in person or sign up for zoom.

Pasts Imperfect is going on our annual summer hiatus! Don’t worry. We will check back in periodically and be back in early August. Feel free to email pitches, ideas, or complaints (although please keep in mind we do this for love rather than money), but we also hope you might be just sipping a hugo in Trastevere and escaping. Ciao!

"Hannibal had no offspring, as far as we know, and no political legacy to speak of, but he is the one who lives on in popular memory. Blame the elephants. 🐘"

Yes, but they teach you this, usually, in a vaguely roman shaped, or inspired, building, in an institution based on supposedly Greek originals, and (when in the USA) situated in a country whose institutions were/are intentionally based on what they understood of the Roman Republic.

With all the talk of history and gaming, I feel like I should bring up Paradox Development Studio's titles (Victoria, Crusader Kings, Europa Universalis)...

there's nothing quite like it, just such a detailed geopolitical simulation, and more than once it's inspired me to read up on a country I'd never heard of before seeing it on the world map.