This week, we look at a new book by Princeton professor Caroline Cheung, Dolia: The Containers That Made Rome an Empire of Wine, and re-view the Roman economy through the lens of massive ceramic vessels called dolia. Then, an update on campus protests on the West Coast from Rita Lucarelli, including important statements from the Classics Department at UCLA and the ACLS. In global antiquity news, a traveling exhibition in Japan looks at the joy of bathing in Ancient Rome and Japan, celebrating AAPI month and the accomplishments of AAACC members, new books on medieval Nubia and Ethiopia, exploring ancient protest in the Odyssey, papyri in the news, new ancient world journals, we announce our big Pasts Imperfect event in the fall, and much more.

In Vino (and its Containers), Veritas by Sarah E. Bond

Early in the 320s CE, a rather posh scholasticus (lawyer) and civil servant from Hermopolis Magna in Roman Egypt named Theophanes, traveled on business to Syrian Antioch. It was to be a two-and-a-half month stay alongside his entourage, but the receipts scribbled on papyrus reveal that the trip would be five months altogether. This cache of papyri recording the group’s extensive travel, food, transport, medicine, tchotchkes, and various other payments, are now collectively known as the Archive of Theophanes (PRyl. 616–651; Talbert 2016). Although seemingly mundane, this document cache provides insight into the life of an elite bureaucrat in the years prior to Constantine becoming emperor in the eastern Mediterranean (see Matthews 2006). In addition to travel insights, Theophanes’ numerous purchases of wine—from a novelty jar shaped like Silenus purchased in Tyre to the numerous wine-soaked lunches bought at various roadside bars—reveal that Roman daily life most often included copious amounts of wine [1]. But how, exactly, was this wine stored, and how did these containers change over time?

Romans blended business with pleasure as easily as they mixed their wine with water (although I am not sure if it was at the same 1:1 ratio). Theophanes’ drinking habits seem to be the norm, rather than the exception. By one estimate, the average Roman drank as much as 250 liters of wine a year—a figure which averages out to almost a bottle a day. While the farming, production, and imbibing of Roman vintages have garnered much attention among scholars, the gigantic ceramic containers often used to store them, called dolia, have received far less recognition than their smaller ceramic sister, the amphora. But as Princeton professor Caroline Cheung points to in her new book, Dolia: The Containers That Made Rome an Empire of Wine, this overlooked vessel—a behemoth which could hold over 1,000 liters at its maximum—was the “backbone of the Roman wine trade” (xiv) for centuries.

Throughout Dolia, Cheung underscores the fact that these massive super-containers were impressive, but also expensive and artistically complex to make. As such, they were expected to last decades, making regular repairs essential to protecting them as the “costly investments” they were. And yet, as Rome continued onward into the empire, vintners and merchants began to abandon the use of the massive dolia. This occurred as early as the mid-to-late first century CE, but a more rapid abandonment took hold by the third century, as apparent in new types of ships and storage facilities favored by merchants.

An easily-transportable and cheaper container technology from the north, the barrel, was gaining steam and becoming much more widely used (Cheung 2024: 187). The so-called “barrel revolution” had begun, and with it, Cheung points to the great economic transformation brought about for the timber and wine industries, for craftspeople and their relationships with purveyors and shippers; for consumers; and even in terms of workflows at ports. A few elite villas and dolium makers continued to use the mega-container into the late Roman period, but the third century appears to be the “last gasp” of the container that had once “supersized the Roman wine industry” (196).

In his classic work, L'invention du quotidien (1974), Michel de Certeau parsed the ordinary, spatial rhythms and routines that make up daily life, from walking to drinking to cooking. In a similar fashion, Dolia considers the movement and lifecycle of a container as a trace element for understanding the socio-economic connectivity of the Roman economy. But in a chat about the book with ancient historian Carlos F. Noreña, he remarked on the fact that Cheung’s book goes well beyond simply following a shipping container from its rise to its fall.

This book makes an important contribution to our understanding of the political economy of Roman Italy. By focusing on storage specifically, Cheung is able to unite, as never before, the study of agricultural production and agricultural distribution, topics that are normally examined separately. This gives us a much more granular picture of the daily operations of the complex framework within which commercial products moved during their various “life histories.”

Noreña points out that a firmer grasp on this larger, ancient economic framework can impart a “deeper understanding of the impact of an imperial capital (i.e., Rome) on its own regional hinterland, and a more empirically robust basis for continuing debates about the organization of the Roman economy during a time of imperial expansion and imperial consolidation.” Dolia presents an essential study of a true “feat of clay,” while also recognizing the myriad ancient hands that formed, carried, lugged, and repaired these ceramic beasts in antiquity.

[1] Matthews 2006, 125 calls the Silenus wine jug the “typically tacky” purchase of a tourist, but who amongst us has not bought a lemon-shaped limoncello container in Capri? Although, I would like to note that since I work at a public university, I cannot submit alcohol receipts for reimbursement, which does make me salty that Theophanes could.

[2] Estimates range from 100 liters (Kehoe 2007) to Purcell’s 250 liters (1985: 13-15), based on the amount that Cato (Agr. 57) provided enslaved agricultural workers.

News from Campuses

The University of California Los Angeles Department of Classics released a statement on the university’s failure to protect student protestors. Read it in its entirety here.

“We believe that the real chaos of the past few days at UCLA has not come from the Palestinian Solidarity Encampment but rather from the university administration’s mishandling of a peaceful protest that they initially seemed to have supported.”

The UC Berkeley Palestine Encampment by Rita Lucarelli

Among the pro-Palestinian encampments that keep growing in number throughout the American universities and abroad, the one in Berkeley has not been featured much in the news, and the reason why is easy to guess: this is a pacific, quiet encampment, where violent clashes with counter protesters or with the police, which is what mainstream media are currently focusing on, are not happening.

The students camping around Sproul Hall, the same place where in the 1960s the Free Speech Movement gained momentum, have transformed our campus in a renewed community space where students, faculty, staff and alumni of UC Berkeley as well as local activists, anti-war groups and unions leadership and members offer daily programs of lectures, teach-ins, poetry, and art.

The encampment is a welcoming space for all; in a few major events, a colorful and diverse crowd has been attending and it has been pacifically protesting the genocide of the Palestinian people and requesting the university to divest from Israel; the Faculty and Staff Rally on May Day and an emergency rally for protesting the bombing and ground invasion of Rafah on May 7 are among them.

In the afternoon of May 14, after negotiations that went on during these last couple of days, the students have peacefully decamped. In a letter to the Free Palestine Encampment, Chancellor Christ declared to expedite UC Berkeley Foundation process to divest from weapons manufacturing, mass incarceration, and/or surveillance industries. She also expressed her personal support for an "immediate and permanent ceasefire" in Gaza, rejected criticism of Israel as antisemitic and recognized the "extraordinary death and destruction in Gaza.”

The words that Mario di Savio pronounced in his speech “An End to History” in December 1964, seem to resonate loud and clear across Sproul Hall these days:

“The university is the place where people begin seriously to question the conditions of their existence and raise the issue of whether they can be committed to the society they have been born into…This is part of a growing understanding among many people in America that history has not ended, that a better society is possible…”

The ACLS released an important statement about the 2024 campus protests and the rights of students, faculty, and university staff to exercise their freedom of speech. You can read and endorse the statement here.

Public Humanities and Global Antiquity

It is Asian & Pacific American Heritage Month in the United States, and we are celebrating AAPI scholars. So, let’s pass out some κῦδος: the current co-chairs of the WCC are Asian Americans. And the WCC has been led by Asian American co-chairs for the past 3.5 years! First Caroline Cheung and Suzanne Lye (whose new book Life / Afterlife: Revolution and Reflection in the Ancient Greek Underworld from Homer to Lucian will soon be out with Oxford Press), and now Eunice Kim and Prof. Lye. Second, Melissa Mueller and Tori Lee recently led a two part reading group focusing on the book Ornamentalism by Anne Anlin Cheng. The groups discussed this book and the intersection of classics and Asian American literature.

Over at at Johns Hopkins University, Nandini Pandey hosted a “Futures of Ancient Race” colloquium from March 7-9, bringing together scholars, K12 teachers, grad students, undergraduates, and the general public for conversations about race in the ancient world and how we teach about it as a field. A number of specialists in race and ethnicity in the ancient Mediterranean gathered together with the goal of creating an open educational resource on race and Classics. Based on an idea that Arum Park originally dreamed up in response to her own need for guidance on how to teach such a crucial but complex and sensitive topic, the OER will be designed to equip instructors with the tools to get them started and is set to launch later in 2024.

Finally, Dominic Machado gave a great keynote, “Tam magnus ex Asia veni: Towards an Asian-American Hermeneutics in Classics” at #ResDiff5 and art historian Patricia Eunji Kim curated the show Slow Motion through The Monument Lab. Want to support AAPI scholars? The Asian and Asian American Classical Caucus is a great place to donate if you want to support “undergraduate paper prizes, web hosting fees, speaker honorariums, and special events” put on by the society.

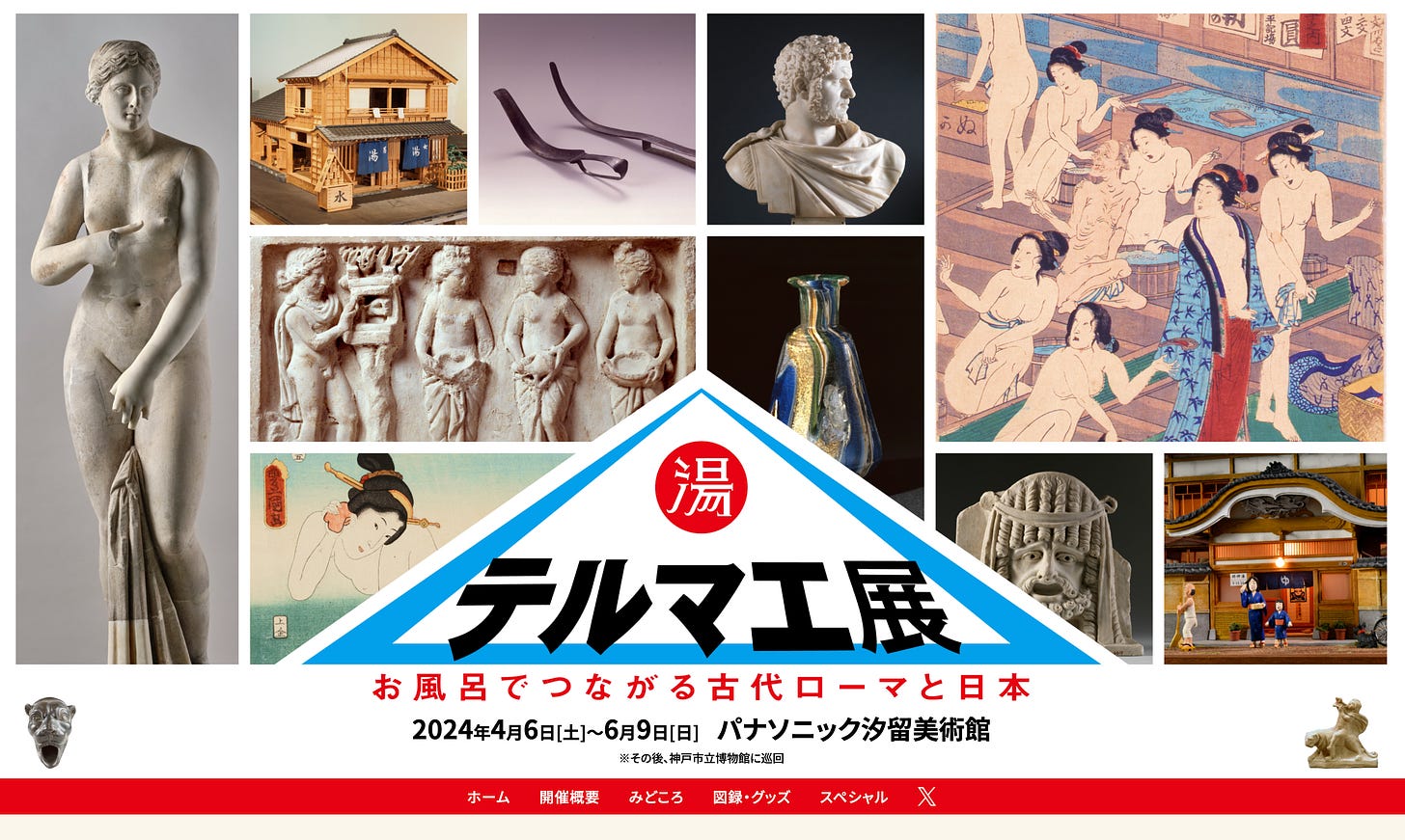

Let me be honest: I have never truly trusted someone who hates baths. Ancient Rome and Japan similarly shared a love for bathing culture and serious tub time. There is a new traveling exhibition on now until June 9th, 2024 at the Panasonic Shiodome Art Museum, Thermae Ancient Rome, Japan, and the Joy of Bathing, curated by Masaki Aoyagi and art historian of Greco-Roman antiquity Kyoko Haga. Bath culture is explored and celebrated within these two cultures through over 100 objects. The exhibit worked in cooperation with manga author Mari Yamazaki, known for her wildly popular series Thermae Romae. The exhibition catalogue is available and perfect for, say, teaching a comparative course on global bathing.

Over at the Byzantium & Friends pod, Anthony Kaldellis speaks to Andrea Achi about “the enduring connections between Byzantium and a number of African cultures, beginning in late antiquity (e.g., Aksum) and continuing into medieval and modern times (e.g., Nubia and Ethiopia).”

A new book by historian of the Middle East and Regius Professor of Hebrew Geoffrey Khan, Arabic Documents from Medieval Nubia, is now open access online. The book looks at Nubia during the High Middle Ages, and “presents an edition of a corpus of Arabic documents datable to the 11th and 12th centuries AD that were discovered by the Egypt Exploration Society at the site of the Nubian fortress Qaṣr Ibrīm (situated in the south of modern Egypt).” The documents have English translations and historical context added, which makes it great for teaching primary sources and incorporating these documents into syllabi. Also make sure to check out Yonatan Binyam’s and Verena Krebs’ new ‘Ethiopia’ and the World, 330–1500 CE, which is free to read online until May 28, 2024.

On the Journal of the History of Ideas blog, Nilab Saeedi explores the roles of the political virtues of “Naṣīḥat” and “Siyāsat,” guidance and government, in the the work of the thirteenth-century Sufi mystic and poet Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī.

Over at Ancient Jew Review, religious studies professor Jae H. Han ruminates on his new book, Prophets and Prophecy in the Late Antique Near East. He discusses how he came to study the Sasanian Empire, Manichaeism, prophethood, and revelation. And in Neos Kosmos, PI co-founder and Homerist Joel Christensen has an essay on “Dissent and violence, an epic Hellenic tradition.” In it, Christensen “looks at the power dynamics in Homeric epics in his attempt to make meaning out of the current campus protests over the Hamas – Israel War.”

In papyri news, papyrologist Roberta Mazza looks at the murky world of selling papyri in “The doing and undoing of papyrus collections: The sale of P.Oxy. XIV 1767”; the Italian National Research Council (CNR) revisits the Herculaneum scrolls and alleges they now know where Plato was buried; and of course, everyone is still waiting on “The Upcoming Sale of the Crosby-Schøyen Codex.” On a totally unrelated (but kind of related) note? Dirk Obbink’s former Waco Castle was recently redone by Chip and Joanna Gaines for an Apple+ show.

The teaser trailer for Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis is out. The director says it is “a Roman Epic fable set in an imagined Modern America,” so get ready for even more innovative (read: stale, misguided) op-eds about how America is Rome. Between this and the release of Gladiator 2 in November, there is proof that for good or ill, the Roman Empire is still living rent free in a lot of people’s minds.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association Vol. 19, No. 2 (2023)

Forum Classicum Nr. 1 (2024)

Dao Vol. 23, No. 2 (2024)

Journal of Late Antiquity Vol. 17, No. 1 (2024) NB Harry Mawdsley “Defeat on Display: The Public Abuse of Usurpers and Rebels in Late Antiquity”

Phoenix Vol. 77, Nos. 1-2 (2023)

TECA Vol. 13 No. 8ns (2023) #openaccess

The International Journal of the Platonic Tradition Vol. 18, No. 1 (2024) “New Light” Special Issue in Honour of the Twentieth Anniversary of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina

Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology Vol. 36 No. 2 (2023)

Studies in Late Antiquity Vol. 8, No. 2 (2024)

Apeiron Vol. 57 , No. 2 (2024)

Interférences Vol. 14 (2023) #openaccess Claudianea et Christiana

The Classical Quarterly Vol. 73, No. 2 (2024) NB Evan Rodriguez “A Homeric Lesson in Plato’s Sophist”

Aethiopica Vol. 26 (2023) #openaccess

Gnosis Vol. 9, No. 1 (2024)

Digital Philology Vol. 13, No. 1 (2024) Fragmentology, Vol. 1

Polis Vol. 41, No. 2 (2024)

Archäologischer Anzeiger 2. Halbband 2023 #openaccess

Florilegium Vol. 37 (2020) NB Jacqueline Murray “Inside and Out: What Did Religious Men Wear Under Their Habits?”

Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 85, No. 2 (2024)

Arion Vol. 31, No. 3 (2024)

Patristica et Mediævalia Vol. 44, No. 2 (2023) #openaccess Recepción y presencia del neoplatonismo cristiano en la fenomenología contemporánea

Pallas No. 121 (2023) #openaccessÉtudier les terres cuites antiques aujourd’hui; Nommer le peuple romain en latin et en grec

Mouseion Vol. 20, No. 1 (2023

Workshops, Exhibitions, and Lectures

Thanks to a grant from the University of Iowa’s OVPR, Pasts Imperfect will be hosting a day of events focused on public writing in the fall. Join us for an in-persons panel at the Stanley Museum of Art (Iowa City, IA) and online via Zoom, discussing how and why we write for the public as art critics, historians, journalists, editors, and non-fiction writers. The panel will include Hrag Vartanian, EIC and co-founder of Hyperallergic; Stephanie Wong, editor and co-founder of Pasts Imperfect; and Jennifer Banks, Senior Executive Editor at Yale University Press. The panel is moderated by writer and editor DK Nnuro.

Sign up here (Zoom registration will be sent out in September).

The “Paratexts in Premodern Writing Cultures” conference will take place in Ghent from June 24-26, 2024 and is available online. The conference is organized in the mode of the Database of Byzantine Book Epigrams (DBBE) project, which “aims to explore the nature of paratextuality in premodern manuscripts across language borders and will include papers dealing with the broader cultural and historical ramifications of paratexts.” A workshop on “Data-driven Approaches to Ancient Languages” will be held on June 27, 2024.