Pasts Imperfect (5.15.25)

The Future of Ancient History, Ptolemaic Mummy Wrappings, Ancient Maya Blue, Authoritarianism in the Late Roman Republic and Today, & Much More

This week, ancient historian Neville Morley reviews a new book on the past and future of a discipline: What is Ancient History? Then, the Ptolemaic mummy wrappings of Petosiris, recreating Maya Blue, reconstructing the ancient lighting in the Parthenon, a revealing Ge’ez colophon from the 16th century, public scholars contextualize the history of the conclave and the chosen name of the new pope, a new open access book on authoritarianism in the ancient Roman republic, new ancient world journals, and much more.

Walter Scheidel, What is Ancient History? (Princeton University Press, 2025): a review by Neville Morley

If Walter Scheidel can outline the whole of what he calls ‘foundational history’, the story of human development since the end of the last Ice Age, in a single chapter, then I’m sure I can sum up his rich and complex polemic in fewer than a thousand words. In his new book, posing the question of what ‘ancient history’ means, in the eyes of its academic practitioners in western universities, is for S. a means to highlight its chronological and geographical limitations and its problematic fixation on the supposed specialness of one ancient culture. It could and should be so much more.

The second chapter charts how this conception of ancient history came into being since the eighteenth century, through the twin-track process of the professionalisation and institutionalisation of Altertumswissenschaften on the one hand and emerging nationalism and cultural chauvinism on the other, both of which privileged ‘GreeceandRome’ to the exclusion of other cultures. They also embedded a lot of problematic assumptions and practices that still bedevil the field today. S. emphasises that ‘ancient history’ has always changed and so can change again; the comparative world history practiced by C18 Göttingen historians, trampled underfoot by narrow-minded philologists, can be reborn in a new form.

What form does this new ancient history need to take? ‘Foundational history’ was global in both scope and impact; as S. argues in Ch. 3, it needs to be studied and taught accordingly. This does not mean that everyone must write planetary-scale histories; that is just one form that the new ancient history takes, alongside contextual approaches (traditional studies conscious of what’s going on beyond a single cultural context), the explicit study of connectivity (without falling into old-fashioned notions of influence), and full-blown comparative projects. The future S. envisions is collaborative, to ensure the necessary expertise; he is well aware of the dangers of superficial and ill-informed generalisations on the basis of a single memeable theory, and of dependence on individual polymathic geniuses.

His vision makes relatively few demands on ancient historians, or at any rate the demands are somewhat vague (‘there is merit in this indeterminacy’: 164). Most, he implies, will carry on their research as normal with a bit more contextualisation and cultural awareness and a bit less specialised jargon (but will presumably make serious efforts to expand the scope of their teaching; more might have been said about this). More might be hoped for in future; if younger colleagues are freed from the tyranny of language exams and the normative expectations of traditional disciplinarity, so that minority approaches are protected, they might seize the opportunity to expand the scope of the discipline.

I must admit that I would like a little less indeterminacy. Being told in abstract terms what this foundational ancient history will be like, and how it presents a powerful claim for present relevance, is less effective than being shown some examples. This isn’t a zero-sum game – everyone needs to read both books – but one of the great merits of Jo Quinn’s How The World Made The West is its use of case studies and anecdotes to advance its historiographical claims, rather than just telling us what they are. Perhaps S. doesn’t want to make his plans look too radical or doctrinaire to potential allies. Instead, the book comes to life in the final chapter, giving the discipline of Classics a good kicking for its narrowness, ethnocentrism/racism, linguistic and textual fetishism, unearned and illegitimate prestige, and appropriation of an unfair proportion of resources in order to maintain language teaching.

The lesson? Abolish Classics, and a bright future opens out for foundational history!

Although my walk-on part in this book is as a stuffy establishment defender of Classics, I’m happy to concede the merits of much of this criticism. Where I hesitate – and not purely out of self-interest, as I am old, and grow my own vegetables – is whether the proposed demolition of the discipline is necessarily the step that will restore ancient history to greatness and intellectual credibility. S.’s concluding ‘Can We Do It?’ section vacillates between playing Fantasy Faculty on unlimited resources cheat mode and identifying weaker disciplines that can be thrown to the cost-cutting wolves in order to save ancient history—however much he insists that ‘change must not come from the barrel of the budgetary gun’. But organisational reconfiguration is already a reality in many universities. And these reorgs are driven not by academic concerns but by senior management or state funding decisions. They usually involve job losses rather than the development of new areas of teaching and research, certainly as far as the humanities (and social sciences outside the Law Faculty and Business School) are concerned. It isn’t only Classics in trouble.

S. briefly acknowledges that others are on the chopping block – but mostly subsumes this into dismissive remarks about ‘permacrisis’ as the humanities’ long-standing rhetorical gambit to assert their relevance, responding to modernity and the rise of science by insisting on the existence of special fields of human experience that only they could address. This seems oddly complacent. Does it not also apply to history, including foundational history? After all, history’s claims to authority and relevance are now questioned both by the expansion of science (and scientistic fields like economics and social psychology) into traditionally humanistic areas and by the equally strident anti-expert, anti-elitist claims of ‘common sense’ and ‘doing your own research’.

At least as presented here, foundational history is about content. Knowledge of the (dramatically expanded) past, rather than a set of intellectual tools for studying the past and its present manifestations. Other than the exoticism of some of its material, it’s not obvious that this has a compelling claim to attention in the face of the sweeping claims of e.g. Big Data, extrapolation of historical DNA analysis, Ancient Aliens, or ChatGPT in generating ‘historical’ content; nor that its findings, however foundational this period may be, actually speak to the present in a manner that will be seen as useful by those with power and money. ‘Why?’ may be a more pressing question than ‘what?’ when it comes to ancient history today. But anyone concerned with ancient history still needs to read this book—and engage with its questions, even if you come up with different answers.

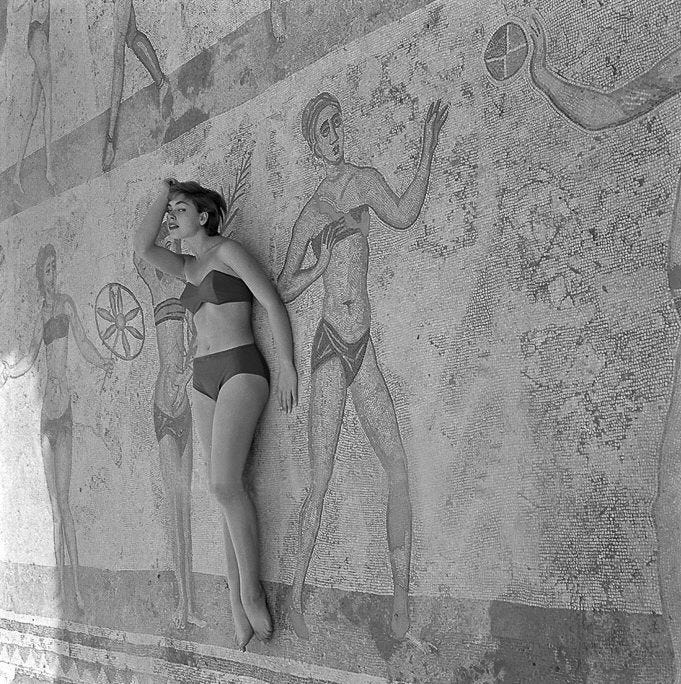

Global Antiquity and Public Humanities

Over at the Getty’s YouTube channel, they have a new educational video on their inscribed mummy wrappings of an ancient Egyptian man living during the Ptolemaic period named Petosiris, son of Tetosiris, dating to 300-100 BCE. The video is connected to The Egyptian Book of the Dead exhibition that ran at the Getty Villa from November 1, 2023–January 29, 2024.

Within UNC’s Bookmark This, classicist Suzanne Lye and her new book, Life / Afterlife: Revolution and Reflection in the Ancient Greek Underworld from Homer to Lucian, are featured. We’d also like to congratulate UNC historian Kathleen Duval for winning the Pulitzer Prize last week for her book, Native Nations: A Millennium in North America. Finally, some κῦδος are due to translator and Ovid scholar Stephanie McCarter, who won a Guggenheim. Nicely done!

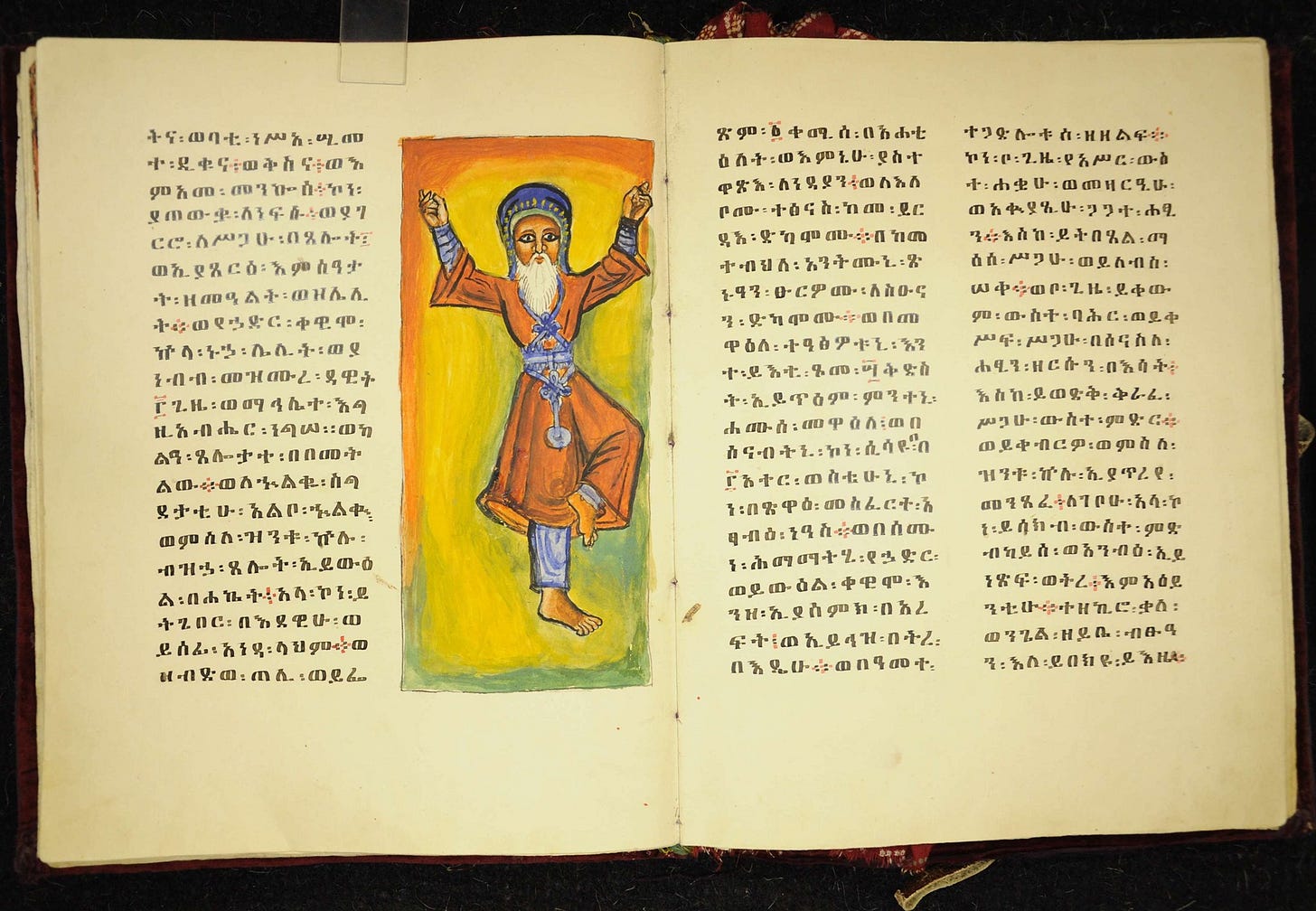

A new article in Azania by Dorota Dzierzbicka and Daria Elagina looks at the context of a 16th century Ge’ez account by an Ethiopian monk named Takla ’Alfā. As they note, “the narrative provides valuable insights into the late sixteenth-century community of Dongola, complementing recent results of excavations on the site. Takla ’Alfā’s account also sheds light on Sub-Saharan trade routes and the importance of the city during a period previously considered obscure due to limited textual sources.” We do love a medieval colophon—we just wish the Vatican had digitized this manuscript prior to this OA article coming out (it is Vat.et.44).

Habemus papam, y’all—and he is a proud White Sox fan—but did you catch all those professors on CBS News? We just wanted to say we are proud of Candida Moss for her public scholarship alongside other religion experts like Anthea Butler, who are all stepping up to tell us about the history of the papacy and the new pope’s chosen name: Leo XIV. Both scholars are featured in the news video below.

In the digital pages of LiveScience, Kristina Killgrove reports on the “Secret of ancient Maya blue-pigment revealed from cracks and clues on a dozen bowls from Chichén Itzá.” As she notes, Maya blue was only discovered by modern researchers in 1931 but was a pigment used frequently in the Late Preclassic period (300 BCE to 300 CE).

For decades, scientists tried to decode the precise method of manufacturing Maya blue, but they did not succeed until 2008. By analyzing traces of the pigment found on pottery at the bottom of a well at Chichén Itzá, a Maya site in the Yucatán Peninsula, a team of researchers led by Dean Arnold, an adjunct curator of anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago, determined that the key to Maya blue was actually a sacred incense called copal. By heating the mixture of indigo, copal and palygorskite over a fire, the Maya produced the unique pigment, he reported at the time.

But at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in Denver on April 25, Arnold presented his discovery of a second method for creating Maya blue. The new research has been published in Arnold's book "Maya Blue" (University Press of Colorado, 2024).

Homer scholar, simile expert, and award winning classicist Deborah Beck wrote a pretty badass op-ed for the Austin American-Statesman. In it, Beck notes that Senate Bill 37, under consideration within the TX Legislature, “would change our public universities so radically.” Why? Because hiring faculty positions in “liberal arts, communication, education and social work — but no other fields — become the responsibility of a state governing board whose members would not necessarily have either disciplinary expertise in the relevant academic subjects or training in college-level teaching and learning.” Read the op-ed for more, but as she notes, fostering transformative learning is a core objective of faculty-led hiring practices.

In the Annual of the British School at Athens, Juan de Lara has a great new open access article on using “3D digital technologies, along with physically based lighting simulations, to recreate the ambient and architectural conditions that existed in the original temple design” of the Parthenon at Athens. We are big fans of all the graphs and renderings of what it looks like at different times of day when the sun hits it.

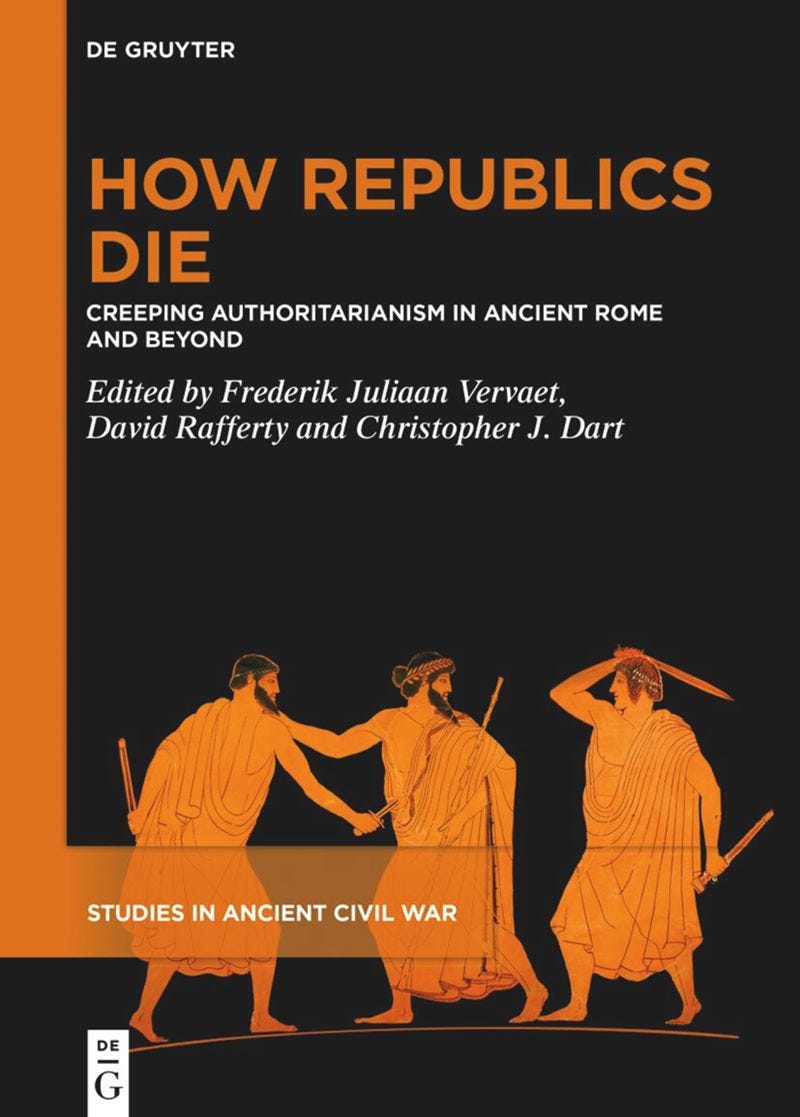

There is a new, open access book out that is perhaps a little too relevant—but is necessary reading in this fascistic moment. Edited by Frederik Juliaan Vervaet , David Rafferty, and Christopher J. Dart, How Republics Die Creeping Authoritarianism in Ancient Rome and Beyond is a free volume with some resonant chapters. From scholars like Amy Russell on Cicero, to ancient economist James Tan addressing the fall of the Roman republican economy, to Francisco Pina Polo’s cross comparison of the Roman Republic and the Civil War in Spain (1936–1939): Definitely give this a glance.

On May 1, 2025, the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), the American Historical Association (AHA), and the Modern Language Association (MLA) filed a lawsuit in federal district court, “seeking to reverse the recent actions to devastate the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), including the elimination of grant programs, staff, and entire divisions and programs.” We will keep you updated, but it is good to see academic groups band together in the wake of the damage done to the NEH, ODH, NEA, and now the Library of Congress, with the firing of Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden.

And finally? Listen to the Lesche: Ancient Greece, New Ideas podcast to hear Walter Scheidel discuss his new book with Johanna Hanink, but also make sure to tune in and hear Sasha-Mae Eccleston discuss her stellar book, Epic Events: Classics and the Politics of Time in the United States since 9/11.

Antiquity Journal Issues (by yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Archaeology of Western Anatolia Vol. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Archäologischer Anzeiger 2 Halbband 2024 #openaccess

Classical Journal Vol. 120, No. 4 (2025) NB Michael Freeman, “The Body of the Scribe”

Dionysus ex machina No. 15 (2024) #openaccess

Frankfurter elektronische Rundschau zur Altertumskunde No. 55 (2025) #openaccess

Gephyra Vol. 29 (2025) #openaccess

Hermes Vol. 153, No. 2 (2025)

Latomus Vol. 83, No. 4 (2024)

Mediterranea Vol. 10 (2025) #openaccess Ulrich Jasper Seetzen’s Travels to the Middle East: Ways of Knowing and Translation

Res Diff Vol. 2, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess NB Chance Bonar “Reconsidering the Fictionality of Enslavement to Deities in the Hellenistic and Roman Near East.”

Studies in Late Antiquity Vol. 9, No. 1 (2025)

American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly Vol. 99, No. 1 (2025)

NABU: Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 2025-1 (notes 1 à 36) #openaccess

Studia Iranica Vol. 52, No. 1 (2023)

The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Vol. 87, No. 2 (2025)

Journal of the Bible and its Reception Vol. 12, No. 1 (2025) NB Anders Martinsen, Martijn Stoutjesdijk “Obscuring New Testament Slavery: A Study of the Translation History of Δοῦλος”

Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft Vol. 116, No. 1 (2025)

Digital Philology Vol. 14, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess Big Data & Manuscript Studies: Some Reflections on a Methodology

Le Moyen Age Vol. 130, Nos. 3-4 (2024) Les âges de la vie au xive siècle

Lectures, Exhibitions, and Workshops

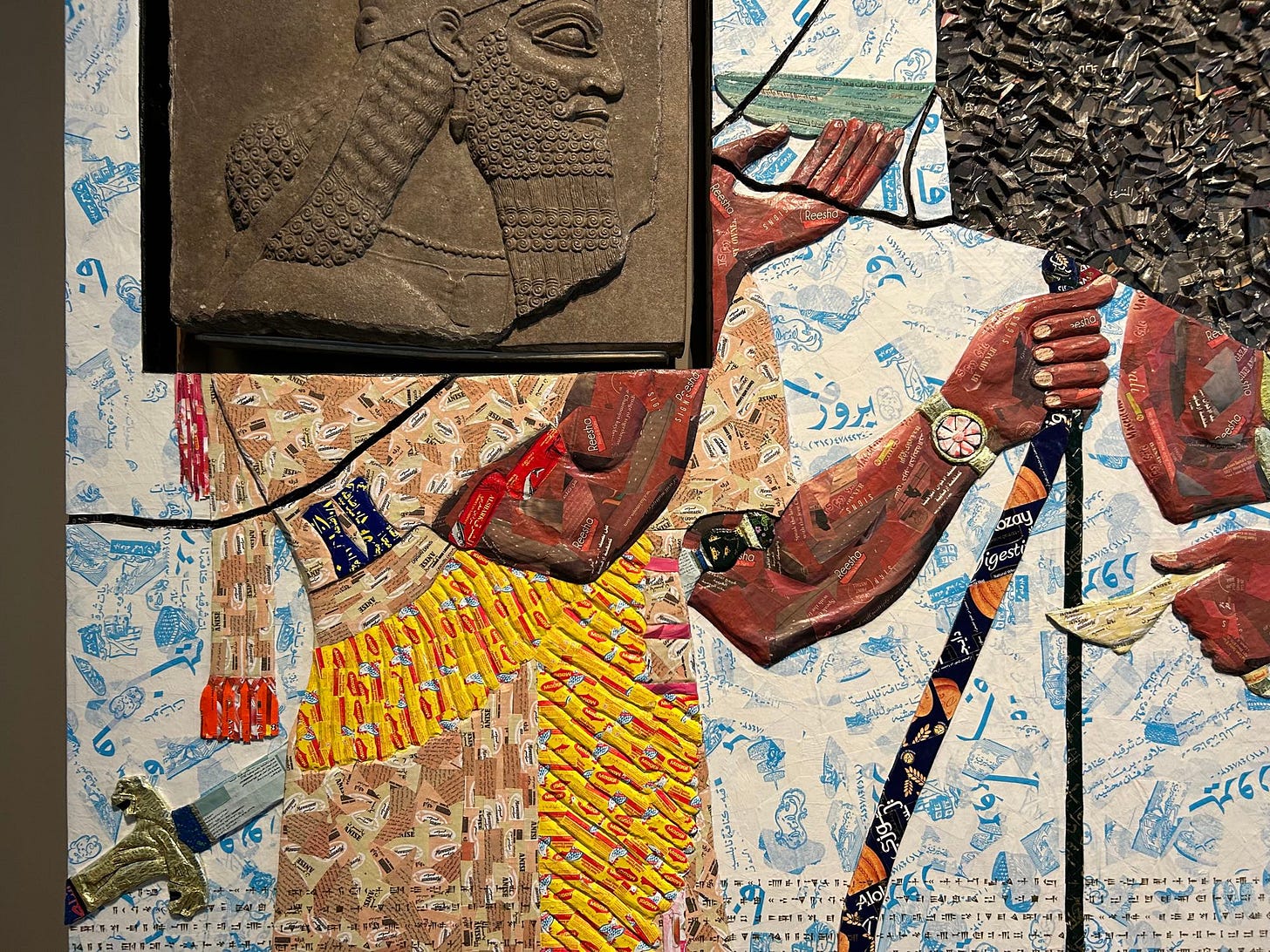

On May 13, 2025, Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz's exhibition opened at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. Allspice | Michael Rakowitz & Ancient Cultures is open until October 31, 2025 or you can see a few of his works at ISAC in Chicago.

The May 21st (3.30pm BST=10:30am EST ) online Seminar of the Cambridge, UK Sino-Hellenic Network will feature Eric Hutton presenting “To China and Back: The Roundtrip Voyage of a Platonic Notion.”

Also on May 21st (at 6:30 PM BST=1:30PM EST) and also in Cambridge and online, the VIEWS (Visual Interactions in Early Writing Systems) Project Seminar will be a double header: Kit Lee (East China Normal University) on “Haptic Knowledge and Iconicity in Knotted String Records,” and Logan Simpson on “Script Design, Community Needs, and the Path to Unicode.”

Ancient medicine expert Chiara Thumiger will present “Galen on the Question of Metabolism Body and Environment in Ancience Medicine” as part of the Centre for the Study of Medicine and the Body in the Renaissance (CSMBR) online lecture series on Tuesday, May 27th, 5pm CEST=11am EST. You can also watch past lectures at the Centre on YouTube.