Pasts Imperfect (4.6.23)

Recovering Ancient Artisans, Children in Roman Egypt, Peruvian Murals, and More

This week, Sanchita Balachandran, director of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and conservator of archaeological materials, discusses her work recovering the lives of ancient artisans. Then, exploring children’s urban environments in Roman Egypt, divine infants minted onto ancient coinage, newly discovered Peruvian murals, a new exhibition on the Bronze Age Chinese city of Anyang, why Christians need to just abandon the “Christian Seder,” new ancient world journals, upcoming zoom lectures, and much more.

Recovering the Lives of Ancient Artisans by Sanchita Balachandran

When I look at this painted image from the 6th century BCE of a young man in a ceramics shop selecting just the right pot to buy, I smell wet clay. It’s the ubiquitous scent of the potter’s workshop, a reminder of how a maker took fluid earth and turned it into a gleaming, velvety, useful thing that still winks at us in the light, 2500 years later. But where is the potter in this picture? Everywhere and nowhere. He/she/they are not painted in, and yet, the pot and its image exist because they did, their skill and creativity forever embedded in fired clay.

This pot bears an inscription that claims its maker’s identity, because it is signed “Phintias egraphsen” (“Phintias painted this”) in tiny orange-red letters that dance around the man examining merchandise. We can imagine this Phintias, possibly a migrant worker or immigrant from Elis, making pictures in Athenian clay, marking a presence we can still read today. But what else can we know of the real identity of Phintias and those few ancient makers who signed as painters or potters (scrawling “[So-and-so] epoiesen,” or “So-and-so made this”), let alone the many who did not sign their pots? Where are the potters? Nowhere and everywhere.

I’ve been searching for these ancient makers in their archives—the pots they created. I pay attention to places, gestures and habits on pots that hint at who these potters were, what their working lives were like, and how we might reconstruct the relationships they had with their pots, and each other. I attempt to re-center and recover them as real people with real bodies and real creative minds in addition to the “hands” that our art historical scholarship often prioritizes. This means tracking ceramics production from literally the ground up, following the clay as it becomes a thrown and trimmed vessel, tracing the preparatory drawings still present on pots, sourcing the brushes used to paint the images that show us their world, and standing kilnside as clay becomes resilient ceramic.

Since 2015, when I co-taught the Johns Hopkins University undergraduate course “Recreating Ancient Greek Ceramics” with contemporary potter Matthew Hyleck, I’ve been trying to complicate the story of how we think Athenian ceramics were produced. Most scholars are still trained on Joseph Veach Noble’s accessible The Techniques of Attic Pottery, but his version is limiting, formulaic. Our class’ short film “Mysteries of the Kylix” highlights how nuanced, flexible and creative ancient potters must have been, a reality we can still read in the chemical microstructures of their pots.

Doing this kind of work is necessarily collaborative, multidisciplinary and exploratory, and feels especially important considering that a significant percentage of these workers—poor Athenian citizens, migrants and immigrants, freed and enslaved people, and women and children across these statuses—are underrepresented in our traditional forms of archaeological, epigraphic or literary evidence. Therefore, we have to follow every small lead, as Tiya Miles does with an embroidered sack passed down through three generations of Black women. Because the challenge is to “unflatten” these people as Nick Sousainis might say, to be with them in ways that attempt what Saidiya Hartman calls “critical fabulation” or Rebecca Hall terms “the measured use of historical imagination.”

As researchers, we’re often looking at these makers’ objects from a remove, gauging profiles or peering at pictures that just happen to be on pots, or organizing them into categories based on shape or attribution. But when ancient potters depict themselves, they look into or over their pots, their eyes bright with focus whether painted in or scratched out in sgraffito: their presence is all controlled and yet loosely held energy, packaged kinetic force that they channel into their things.

To read and talk with contemporary potters is to be aware of how much they care about making pots that live, that breathe, that tell stories when they are held and used. Perhaps the ancient makers in the Athenian Kerameikos cared about this too. I like to imagine Phintias’ shop, the reek of damp clay heavy in the air. Perhaps a co-worker, even the Berlin Painter who is thought to have trained with Phintias, picked up this pot the way that potters do today; turning it over to examine the foot, running a thumb up the rise of the inner profile, pinching clever fingers at the rim, and judging with admiration that, yes, this pot feels alive.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

In the realm of social archaeology, April Pudsey’s and Ville Vuolanto’s important article on “Children’s Urban Environments in an Ancient City: Social and Physical Realities,” is now open access. In it, they use the city of Oxyrhynchos in Roman Egypt—a city with 15,000-30,000 people in the high empire, of which almost half were under fifteen years of age— as a case study for reconstructing the role of the city in the lives of young people. If you like this article, you may also be interested in the newly published A Social Archaeology of Roman and Late Antique Egypt: Artefacts of Everyday Life, edited by Ellen Swift, Jo Stoner, and April Pudsey in 2022. As they demonstrate, there is so much more to learn about daily life in antiquity through material culture— such as the child’s sock below.

For more on this polychromatic sock and the innovative use of multispectral imaging (MSI) techniques on it and other late antique textiles from the British Museum, see this exciting article by Joanne Dyer, Diego Tamburini, Elisabeth R. O’Connell, and Anna Harrison in PLOS ONE.

In coinage news, numismatist Austin Goodwin Andrews discusses “Wee Deities on Coins” for the American Numismatic Society (ANS) blog. In it, he looks at the projection of human infancy onto Greco-Roman deities, using Zeus, Herakles, and Eros as his main case studies. Andrews concludes by saying,

Greek and Latin sources often frame the gods with epithets such as “immortal” or “deathless” to contrast them with our mortality and its necessary conclusion. This framing, however, did not preclude their starting points, i.e., having been conceived, born, and reared. There is a vivid contrast to the considerable power, influence, and authority associated with the divine against the weakness, dependency, and stark mutability for which babies are famous—and people, too, more generally.

One question Andrews does not answer through his many examples is the focus on male babies on coinage. Why are male divine infants so much more heavily represented than female ones on these coins?

As Hyperallergic covered last week, archaeologists have unearthed a number of painted murals within Pañamarca. The ceremonial epicenter was created around 550-800 CE and was part of the Moche civilization, in the lower Nepeña Valley of northern Peru. Reporter Taylor Michael notes that one new mural figure uncovered recently “carries a weapon or a quipu, an Indigenous numerical accounting device…Historians hypothesize that the images, which date back nearly 1,400 years, could represent artists’ attempts to experiment with portraying movement or narrative.” Researchers and archaeologists Jessica Ortiz Zevallos, Michele Koons, and Lisa Trever of the PIA (Archaeological Research Project: Archaeological Landscapes of Pañamarca) revealed these findings at the annual meeting of the Institute of Andean Studies in January.

The second volume in the Handbook of Ancient Afro-Eurasian Economies has been published. It is edited by Sitta von Reden, in collaboration with Lara Fabian and Eli J. S. Weaverdyck. Volumes I and II are open access and able to be read digitally or downloaded for free. From Milinda Hoo’s chapter on “Globalization beyond the Silk Road: Writing Global History of Ancient Economies” to Lauren Morris’ exploration of “Economic Development under the Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia to the Kushan Empire: Empire, Migration, and Monasteries,” this nearly 1000-page handbook focuses in on “nodes of consumption” and is well worth a gander.

Over at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, the exhibition “Anyang: China’s Ancient City of Kings” is on view in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery now until April 28, 2024. The curators, J. Keith Wilson and Kyle Steinke, note that the exhibition: “brings together more than 200 artifacts—including jade ornaments, ceremonial weapons, ritual bronze vessels, bells and chariot fittings—to examine the Shang state and artistic achievements of those who lived in its capital some 3,000 years ago.” The Bronze Age site of Anyang has a special tie to the museum, since it was previously supervised by archaeologist Li Chi (李濟, 1896–1979), then on staff at the Freer Gallery of Art. As the museum underscores, this exhibition celebrates archaeological research as well as Sino-American relations.

The Jewish holiday of Pesach (Passover) is from April 5 to April 13, 2023 this year. In case you need a reminder, “Christian Seders” are offensive and not a good idea. The Council of Christians and Jews (CCJ UK) has a good explainer to consult on why this is. As Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg noted a few years back: “Christian seders are appropriationistic, problematic, and also not historically accurate.”

In case there were any doubts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is having quite the month. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) reports: “More than 1000 artifacts in Metropolitan Museum of Art catalog linked to alleged looting and trafficking figures.” The objects span from Egypt to India to Italy. On March 30, 2023, The New York Times noted that a famed headless statue of Septimius Severus was seized in February. In the 1960s, it was looted from Bubon in Turkey along with many other objects. Another 15 pieces were also repatriated to India recently. As art crime professor Erin Thompson has noted: there might be a few forgeries to address in addition to these repatriation efforts.

Also? The Oriental Institute changed its name to the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, West Asia & North Africa. 👏 ISAC 👏

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib)

American Journal of Philology Vol. 143, No.4 (2022) Diversifying Classical Philology, Vol. 2

Apeiron Vol. 56, No. 2 (2023)

Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica Vol. 51 (2019) #openaccess

Mediterranea Vol. 8 (2023) #openaccess

Hesperia Vol. 92, No.1 (2023)

Studies in Late Antiquity Vol. 7, No. 1 (2023) NB Maia Kotrosits, “The Ethnography of Gender: Reconsidering Gender as an Object of Study” & Timothy Pettipiece, “Eastern Sages in Roman Egypt: Manichaean Trajectories through a “Global” Late Antiquity”

Speculum Vol. 98, No. 2 (2023)

Novum Testamentum Vol. 65, No. 2 (2023)

Philological Encounters Vol. 8, No.1 (2023)

Revue Mabillon Vol. 33 (2022)

Arheologia = Археологія No. 1 (2023) #openaccess

Journal of Urban Archaeology Vol. 7 (2023) #openaccess Anomalous Giants

Classical Philology Vol. 118, No. 2 (2023)

Méthexis Vol. 35, No. 1 (2023)

Religion in the Roman Empire (RRE) Vol. 8, No. 2 (2022) #openaccess NB Jeremiah Coogan, “Misusing Books: Material Texts and Lived Religion in the Roman Mediterranean”

Ancient Philosophy Today Vol. 5, No.1 (2023) NB Orestis Karatzoglou. “Empedocles’ Epistemology and Embodied Cognition”

Acta Archaeologica Vol. 93, No. 1 (2023) Aspects of Ancient Greek Cult II. Sacred Architecture, Sacred Space, Sacred Objects: An International Colloquium in Honor of Erik Hansen

Journal of Late Antiquity Vol. 16, No. 1 (2023) NB Valentina A. Grasso, “ Historicizing Ontologies: Qur'ānic Preternatural Creatures between Ancient Topoi and Emerging Traditions”

Shedet Vol. 10 (2023) #openaccess

Journal of the History of Collections Vol. 35, No. 1 (2023) NB: Gabriella Cirucci, “Apelles’ Aphrodite Anadyomene: the itinerary of a sacred gift”

Ancient World Lectures, Conferences, and CFPs

For the “East of Byzantium” consortium on Tuesday, April 25, 2023 at 12:00 PM (EDT, UTC -4), Joel Walker will discuss “The Öngüt Connection: Christianity among the Turks of Medieval Eurasia” on Zoom. The lecture explores “the Christian tradition of the Öngüt Turks of Inner Mongolia, who played a pivotal role in the rise of the Mongol Empire (1206–1368).” To register for the webinar, go here.

The Society for Ancient Mediterranean Religions (SAMR) is hosting a zoom flash conference discussing evidence for and methodological issues in the study of materiality and late antique religion from April 25-27, 2023 at 6 pm ET:

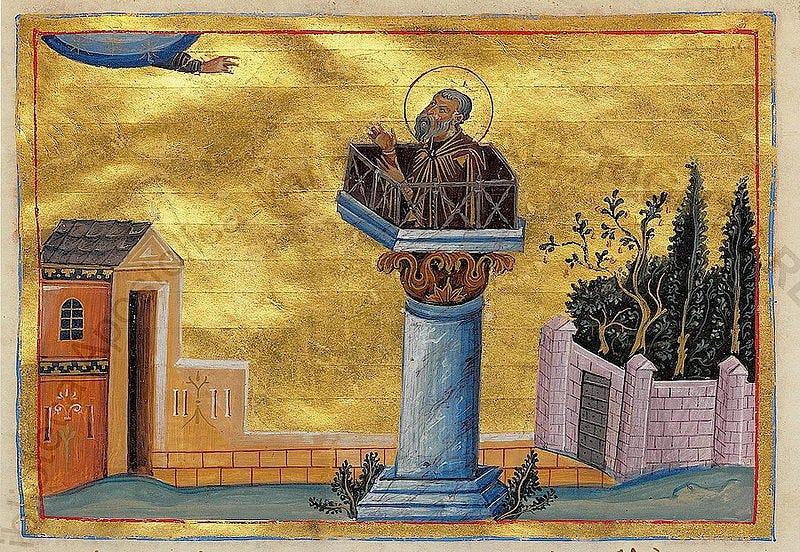

Tuesday, April 25, 6:00 pm ET: Dina Boero, “The Space of a Stylite: Columns and their Topographical Contexts.”

Wednesday, April 26, 6:00 pm ET: Sarah Porter, “Desire in the Archive: A 1934 Excavation in Antioch’s Southeastern Nekropolis.”

Thursday, April 27, 6:00 pm ET: Camille Angelo, “Animating Attachments: An Affective Archaeology of Late Antique Monastic Refectories.”

For more information and to sign up: https://www.samreligions.org/flash-conference/