Pasts Imperfect (4.4.24)

Enslaved Scribes & the Bible, Open Images, Recreating Feudal Japan, and More

This week, Tim Whitmarsh, the Regius Professor of Greek at University of Cambridge, discusses a new book about enslaved writers and the authorship of the New Testament. Then, the Getty releases 88,000 images under an open license, historians aid in making Shōgun, a Pompeii construction site frozen in time reveals ancient building techniques, walking as a form of dissent for female saints in South Asia, archaeologists speaking up for Gaza, new ancient world journals, a panel on the archaeology of identity at the "peripheries,” and much more.

Dancing with the Devil: on Candida Moss’s God’s Ghostwriters by Tim Whitmarsh

David Bowie’s Let’s Dance is one of the iconic songs of the 1980s: its post-disco beat, spare production and fraught vocals are instantly recognisable. I remember very well the thrill of slipping the vinyl from the single’s cover — which featured Bowie holding the pose, rather implausibly, of a bare-fist boxer — straight onto the turntable. Those crashing drums boomed out, and the paper label spun around merrily, with its simple attribution: ‘Let’s Dance (David Bowie)’.

In the 1980s, the authorship of songs was treated as a relatively simple thing: if you came up with the words and the tune, then the song was yours — as were the royalties (which were, in this case, copious). This was a system that tended to privilege and reward the ‘star’, while downplaying or even erasing the roles of those who helped shape and hone the song. It was not till many years later that the producer of Let’s Dance, Nile Rodgers, revealed how much input he had had into the making of the smash record: he had taken what he described as a ‘folk song’ and transformed it utterly, restructuring it and giving it a wholly new rhythm and feel.

Rodgers has had an extraordinarily successful career as a musician and producer. But the story illustrates just how easy it is for the seemingly straightforward concept of ‘authorship’ to misdirect our attention away from the collaborative labour that inevitably underpins almost all forms of cultural production. And lying in the background of most individual cases like this are larger-scale social processes, which feed off and feed systemic inequalities. The racial dimension in the case of Bowie and Rodgers is a clear illustration of this. Bowie was hardly the first, or indeed last, white man to swell his fortune by appropriating the musical innovations of a person of colour.

Authorship in the Greco-Roman world was in some respects a very different phenomenon. There was no copyright law, and hence no easy way of monetising literary production. When texts were copied and sold on, no royalties flowed back to the author. Copying itself was not a swift, mechanical process, like the hammering out of vinyl singles in the 1980s. It involved sourcing expensive materials, and commissioning the specialist labour of a scribe (often enslaved), who would strain to produce a new text, all the while undergoing incalculable damage to eyes, muscles and bones.

In other ways, however, there are recognisable similarities. In antiquity, authorship was pretty much always imagined as solitary: there are no significant examples from over 1000 years of classical Greco-Roman society of texts being attributed to more than one writer. Classical antiquity could not conceive of authorship in the plural, even in situations where there quite clearly must have been multiple collaborators involved in the creation of the text. Think, for example, of drama: are we really to believe that ancient playwrights took no inspiration from the actors, producers and musicians with whom they worked? The Nile Rodgerses were always written out of the authorship story. And while it is true that accredited authors earned no royalties in antiquity, this does not mean that they did not gain from their fame. Literary prestige always mattered. Individuals, their families, and their wider communities traded on the success of successful texts.

Candida Moss’ God’s Ghostwriters is a brilliant and subtle detective story, which will have repercussions across the entire field of ancient Mediterranean studies. It asks, in calmly rational but resolute tones, who we really think authored the earliest Christian texts. Can we believe that the elite males to whom (practically) the entirety of early Christian textual production is attributed were the only agents involved in the creation of this literature? Who were the Nile Rodgerses of antiquity, whose contributions ended up being left off the vinyl label? Moss does a superb job of reconstructing the multiple voices who contributed to the creation of early Christian discourse.

Inevitably it turns out that those who have been written out of the authorship narrative are those with the least social standing — principally the enslaved. The ‘ghostwriters’ of her title are first and foremost the copyists who helped adapt and refine the Christian message. The low-status artisans whose job it was to turn musings into what we would now call ‘saleable copy’. Moss also demonstrates — with a rare humanity — just how much it cost nonelites to contribute to the formation of modern Christian discourse. This is, among other things, a book about the effects of real labour on the body; about the hunched backs, brittle bones, strained eyes and lashed bodies that were the by-products of early Christian textuality.

For me, as a classicist, what this book dramatises most vividly is the materiality of early Christian literature, its physical embeddedness in ancient society. Ancient books were not simply repositories for grand ideas; they were also artifacts that were created and circulated by real people. Moss brings to the surface the ethical challenges that that conclusion presents: we simply cannot and must not think about early Christian texts without also acknowledging the human (and indeed ecological) damage that enabled their creation and circulation. Nor can we divorce the materiality of Christianity from its message. Christianity did not sit above Greco-Roman antiquity in a free space of pure ideality: it was always joined in a diabolical dance with the realities and inequalities of a society built on coerced labour, and which concentrated most of its wealth, power and prestige in the hands of a tiny elite. Thanks to Moss’s book, we now have a much sharper sense of who the unacknowledged collaborators were who helped shape early Christian literature.

Public Writing about a Global Antiquity

The Getty has made over 88,000 images downloadable in their Open Content database under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0). Why is this good news? This means “you can copy, modify, distribute and perform the work, even for commercial purposes, all without asking permission.” Stop paying so much for image licensing and start illustrating more books and articles with amazing, open access material culture and art. The Public Domain is the best domain.

The FX limited series Shōgun is a global hit, but how historically accurate is it? The show focuses on Lord Yoshii Toranaga (played by Hiroyuki Sanada and based on Tokugawa Ieyasu, 1543–1616) and feudal Japan. Over at El País, they speak to Frederik Cryns, a professor of History at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto, about the three years he spent advising the team. And in another interview at the Hollywood Reporter, show creators (and married couple) Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks remark more on their “painstaking reconstruction” of the time period. One debate they had to decide on? Seating styles.

[The historical advisor] had all this evidence that women in the period we were depicting sat in the tatehiza style [a traditional, formal way of sitting, which involves having one knee raised]. Somewhat later, in the Edo period, people started sitting in the seiza style [the now internationally familiar, Japanese style of kneeling on the floor with one’s butt on one’s heels]. But then our Japanese producers, Hiroyuki and Eriko, told us that Japanese audiences would really expect the characters to be sitting seiza style, because that’s the convention of samurai films and jidaigeki.

At Pompeii, archaeologists have uncovered a building site with tools and roof tiles that provides a window into Roman construction methods and the fact that ancient building was pretty tuff (this is a good pun and I stand by it—SEB).

Writing for Al Jazeera, anthropologist and heritage writer Hilary Morgan Leathem discusses the war in Gaza and argues persuasively that “archaeologists must speak up.”

We must remember that archaeology is inseparable from politics, playing a major role in the making of history, nations, and national identity. We must also remember how the total erasure of heritage often prefigures the destruction of people, which is why cultural genocide is also classified as a war crime under international law.

In regard to the medieval world, medievalist Guy Geltner discusses “When we talk about the Middle Ages: Revisiting the power of periodisation.” Rachel Schine has a forthcoming book on Black Knights: Arabic Epic and the Making of Medieval Race and in the new issue of Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, Cord Whitaker, Nahir I. Otaño Gracia, and François-Xavier Fauvelle have co-edited a special issue entitled “Race, Race-Thinking, and Identity in the Global Middle Ages.”

In Roman slavery studies news, Freed Persons in the Roman World: Status, Diversity, and Representation, co-edited by Sinclair Bell, Dorian Borbonus, and Rose MacLean, will be published in May. In addition, a truly stunning sourcebook spanning Egypt’s Old Kingdom to the early Islamic period is out in April: Slavery and Dependence in Ancient Egypt: Sources in Translation. It is edited by Jane Rowlandson, Roger S. Bagnall, and Dorothy J. Thompson, with contributions from Christopher J. Eyre, Brian P. Muhs, Christopher J. Tuplin, Sarah J. Pearce, W. Graham Claytor, Jennifer Cromwell, and Jelle Bruning. Rowlandson had been working on the sourcebook when she passed in 2018. It is truly a labor of love and respect that these scholars came together to help complete this helpful tome.

On the Byzantium & Friends pod, lover of New Rome Anthony Kaldellis speaks to historian of the Middle East Christian Sahner about “the notion of Islamic history as a field of study. What does it prioritize, who does it tend to see most, and what about everyone else?” I also enjoyed the latest episode, which is a fascinating conversation with Maria Parani of the University of Cyprus, looking at “the emperor's clothing and the staging of his public appearances.” Purple silk is always a statement.

Walking is having a (deserved) moment. Whether reading Ann de Forest’s Ways of Walking, perusing Tim O’Sullivan’s excellent Walking in Roman Culture, or marveling at Angela Impey’s Song Walking: Women, Music, and Environmental Justice in an African Borderland: the long history of walkers goes well beyond just flâneurs. This week, Arpita Das looks at saints in medieval India and their use of ascetic walking as a form of resistance. Poet-saints such as Akka Mahadevi, Lal Ded, and Meera, “chose to walk away from the lives they were familiar with and become wandering ascetics. All three were credited with composing exquisite verses between the 9th and 17th centuries.”

If you are like us, you have been listening to a lot of Beyoncé this week. In the digital pages of Rolling Stone, they have a great essay on a pivotal track: “This Moment to Arise: The Revisionary Genius of Beyoncé’s ‘Blackbird’” The song was originally written in 1968 by Paul McCartney, inspired by the Little Rock Nine.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Historia Vol. 73, No. 2 (2024)

Forum Classicum No. 4 (2023) #openaccess

European Journal of Archaeology Vol. 27, No.1 (2024) NB Scott Ortman, et al. “Transport Costs and Economic Change in Roman Britain”

Erudition and the Republic of Letters Vol. 9, No. 1 (2024)

Journal of Indian Philosophy Vol. 52, No. 1-2 (2024)

L'Année épigraphique Année 2020 (2023)

Journal of Early Christian Studies Vol. 32 No. 1 (2024)

Speculum Vol. 99, No. 2 (2024) Race, Race-Thinking, and Identity in the Global Middle Ages

Humanistica Lovaniensia Vol. 32 (2023) #openaccess Quicquid laborum suscipiebat, amore studiorum suscipiebat: A Collection of Neo-Latin Essays Dedicated to the Memory of Dr Jeanine De Landtsheer (1954-2021)

Rudiae Vol. 8 n.s. (2022 #openaccess

Recherches de Théologie et Philosophie Médiévales Vol. 90, No. 2 (2023)

IPM Monthly: Medieval Philosophy Today Vol. 3, No. 3(2024):

Parekbolai Vol. 14 (2024) #openaccess

Manuscript and Text Cultures Vol. 2 No. 2 (2023) #openaccess Writing orality

Classical Receptions Journal Vol. 16, No. 2 (2024) NB Javier Martínez Jiménez “Lycanthropus adulescens: the classical element in MTV’s Teen Wolf (2011–17)”

CALÍOPE: Presença Clássica Vol. 45 (2023) #openaccess

Public Events Lectures, Calls, and Exhibitions

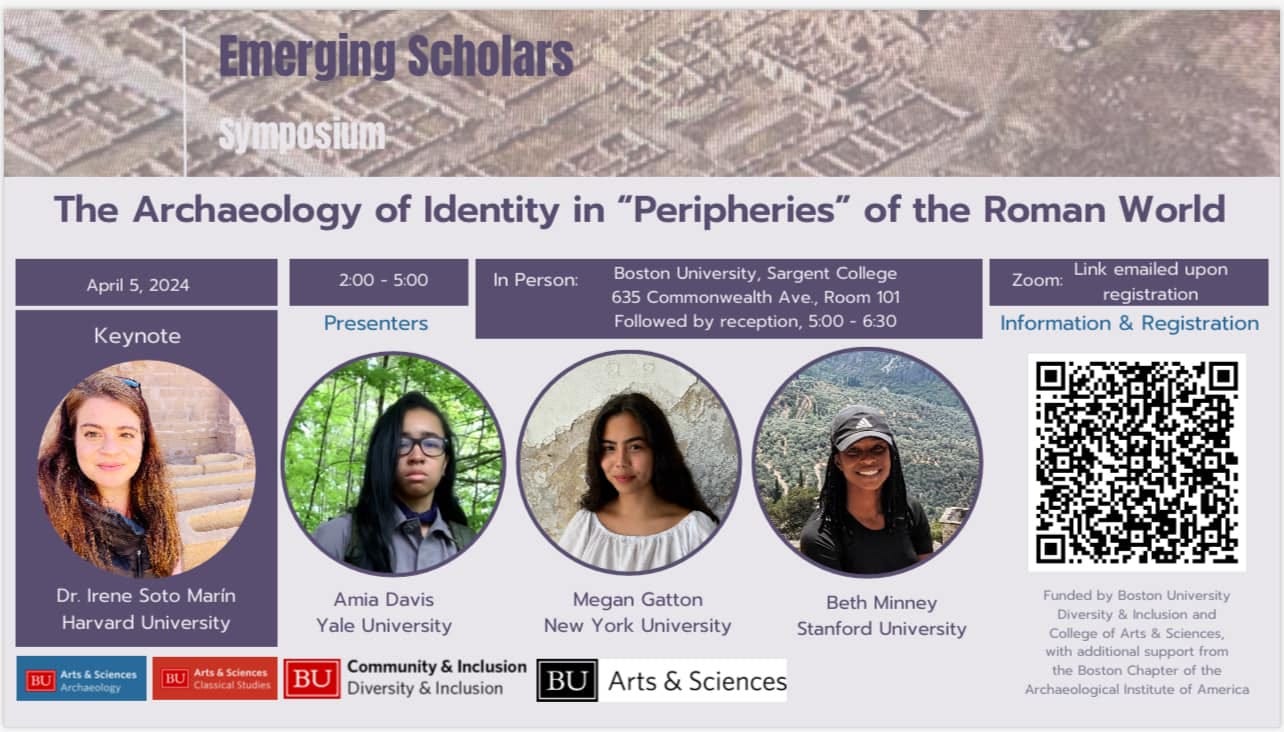

The Archaeology Program and Department of Classical Studies at Boston University invites all to a panel discussion on the topic of “The Archaeology of Identity in “Peripheries” of the Roman World: An Emerging Scholar Symposium.” The symposium is Friday, April 5, 2024, 2pm to 5pm in the Boston University Sargent College, 635 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 101, Boston, MA. Or you can email them for a zoom link upon request. The keynote will be given by Irene Soto Marín.

Over at the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), they are hosting Lyn Green on April 6, 2024 at 1:00 pm ET to speak on: “Feast and Festivity in the Heb Sed Celebrations.” As the abstract notes, “[The Heb Sed] “jubilee” has often been viewed by modern scholars strictly through the lens of its religious practices, obscure symbolic activities, and its meaning in the pharaonic concept of kingship. But it is clear from the reliefs that accompany some depictions of the Heb Sed that music, dancing, and feasting were an integral part of the festivities.” Register for the zoom here.

At the Getty Villa, Archaeologist Carlos Rengifo discusses “The Moche Culture of Ancient Peru: Los Mochicas del norte del Perú” on Thursday, April 11, 2024 | 3:00 p.m. PT. To watch online via Zoom, register here.

The HathiTrust Research Center will host virtual workshops beginning Tuesday, April 16, 2024. Learn more about the three upcoming workshops and how to register on HTRC's page.

The hybrid conference “Indian Philosophy and the Historiography of Philosophy” will take place at the University of Southampton on April 16th and 17th, 2024. “This workshop will investigate relationships between modern Western philosophy and Classical Indian philosophy.”

Have an idea for a PI post? Pitch us via DM.