Pasts Imperfect (4.18.24)

Paying Taxes in Roman Egypt, Pompeian Frescoes, Ancient Foraging & More

This week, ancient historian and taxation expert Irene Soto Marín discusses the risky business of taxes in antiquity. Then, new frescoes at Pompeii, the Africa & Byzantium exhibition goes on the road to Cleveland, a 3,000-year history of pigs, new geographic aids for the ancient Arabian peninsula and Ethiopia, foraging across the globe, a workshop on Gazan archaeology, new ancient world journals, and much more.

The Risky Business of Taxes by Irene Soto Marín

If you are an adult living in the United States, you know that April 15 is right around the time taxes must be filed to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). But taxes—and the illuminating paper trails they create—are not only of interest to the modern world. Those who study the ancient economy are similarly intrigued by the various forms and permutations taxation took in antiquity. Receipts appearing in the papyrological record, literary references, and even glimpses of taxation in kind appearing in historical texts often reminds us of the one certainty that comes with belonging to a larger political unit. After all, the only way a large ancient polity or state was able to ensure its survival and maintain its power was with a functioning fiscal regime. Taxes were not only pivotal, they were definitional. Without taxation, is a state a state?

Taxes are more than tedious documents. Emotions and even danger surround taxation in ways that allow us to access the ancient world in important ways. Those familiar with the Gospel according to Mark may recall a point of conflict between Jesus and the Pharisees and Herodians. Jesus is asked “Is it lawful to give tribute to Caesar or not?” and he offers a surprisingly numismatic response: “Bring me a coin and let me look at it…. This engraving—who does it look like? And whose name is on it? ...Give Caesar what is his, and give God what is his.”(12:13-17) In the Markan tradition, Jesus’s enemies try to put him in a tight political spot, and the Gospels according to Matthew and Luke retell the story. In so doing, each bear witness to broader social division around the question of taxation in the Roman provinces. If you pay taxes to a colonial power, whose side are you really on?

Such division requires colonizers to ask another question: how do you compel conquered populations to contribute to their own domination? How does a state convince its subjects that they are not only necessary, but good. And how do you convince them that if they avoid paying taxes, there will be dangerous penalties? The Edict of Aristius Optatus,[1] — a summary of an imperial edict through which Diocletian instituted a new tax regime in 297 CE — is remarkably sophisticated in its mixture of hopeful and threatening language. Diocletian used a carrot and a stick. The rhetoric is not unfamiliar to those living and paying taxes today. And since it is now April — in this current season of tax, let us gather in solidarity, admit that none of us want to pay taxes, and then spend an empathetic moment parsing the direct, coercive, and threatening language of an ancient taxation edict.

We may find a sliver of inspiration here, too

While the edict opens up with a hopeful note, allegedly aiming to bring an end to the injustice brought about by uneven and corrupt taxation, the imperial narrative quickly moves to describe the urgency and even “enthusiasm” with which taxes should be paid. The edict condemns corrupt taxation as a “most evil and ruinous practice” but then transitions quickly from hope to haste, and ends in a serious warning: “if anyone is caught doing otherwise…they will be in danger.”

The urgency of the language is perhaps a telling window into imperial anxiety: a new taxation system is being instituted in a province that is known to revolt. In fact, it is unclear whether this taxation reform itself was the catalyst, or at least part of the reason, for the big revolt in Roman Egypt of Domitius Domitianus, which did not end until 297/298 CE.

Even before the edict, the population in Egypt was unhappy. Only a couple of years earlier, Diocletian had reformed the entire imperial monetary system, and with it, Egypt’s closed currency system, which had been in place for almost 600 years, was abruptly ended. Not only was this the end of the Greek-style tetradrachms commonly known in the province, but it was also a direct blow to the civic identity of Alexandria, whose coinage, with intricate designs featuring Graeco-Egyptian deities and symbols in the reverse, was a source of pride for the city. And although the numismatic reform did not take place until after Domitianus’ revolt was brought to an end, one can imagine that the announcement of the monetary changes, when coupled with the fiscal reforms, was enough to anger the crowds in Alexandria.

The situation in Egypt, along with the general political anxiety rampant in the latter half of the third century CE seems to have made the Roman authorities nervous, to the point where they felt the need to reiterate that justice would be brought upon anyone who transgressed—even tax collectors. While the edict implies the right of the tax collectors to force the payment, the surviving text ends with a resolute threat to them: behave or die.

There is perhaps some consolation (or at least commiseration) in the fact that taxation has always been a source of anxiety. And yet, this apprehension occurs on both sides of the ledger: both the renderer to Caesar and Caesar himself appear nervous about what might happen if regular people could not or did not pay. Seeing the history of taxes in antiquity less as a tedious and arcane exploration and more as as a way of understanding societal tensions between state and subject highlights the centrality, and most importantly the fragility, of fiscal systems.

Abbreviated Bibliography on Ancient Taxes

Monson, Andrew, and Walter Scheidel (eds.) 2015. Fiscal Regimes and the Political Economy of Premodern States. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Cascio, Elio Lo. 2012. “Finance, Roman.” The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Valk, Jonathan, and Irene Soto Marín (eds.) 2021. Ancient Taxation : the Mechanics of Extraction in Comparative Perspective. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University Press.

Monson, Andrew. 2023. “Taxing Wealth in the Just City: Cicero and the Roman Census.” The Journal of Roman Studies 113: 1–27.

Yiftach, Uri. 2015. “From Arsinoe to Alexandria and Beyond: Taxation and Information in Early Roman Egypt,” The Journal of Juristic Papyrology 45: 291.

Langellotti, Micaela. 2015. “Taxation, Greco‐Roman Egypt.” The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Hollander, David B. 2012. “Taxation, Roman.” The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

[1] P. Cair. Isid. 1. For an online translation see Roger Rees,"22. Edict of Aristius Optatus," Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004, pp. 158-158.

Public Humanities and Global Antiquity

There is no denying that Pompeii has had a moment the past few weeks. The newly discovered frescos depict a number of figures largely connected to the Trojan War: Helen of Troy with Paris (in a dipinto, he is called "Alexandros" in Greek), and a third figure. There is also a fresco of Apollo trying to coerce Cassandra. The stunning artworks were unearthed in a Pompeiian banquet hall. The best photos were taken by archaeologist at the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, Sophie Hay. And as Donna Zuckerberg has noted, the cutest part is probably the good boi below. In addition to the frescos, the new series Pompeii: The New Dig worked with a number of legit Pompeii scholars for its new episodes, which began airing on the BBC this week in the UK, but will begin to air on PBS on May 15, 2024 for Americans.

Congratulations are in order to Chris Waldo, who was awarded a Loeb Classical Library Foundation Fellowship for 2024-25 for his book project: Classical Reception in Asian American Literature. As the UW Department of Classics notes:

Waldo’s book will be the first scholarly monograph on the topic of classical reception in Asian American literature, laying the groundwork for a burgeoning new subfield of Classics. In it, Waldo explores the works of Quan Barry, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Johanna Hedva, David Lau, Chang-rae Lee, Vi Khi Nao, Hoa Nguyen, and Ocean Vuong, examining their engagements with the classical tradition. In addition to broadening our understanding of classical reception, Waldo hopes that the book will demonstrate that the field of Classics has been expanding to be more inclusive of diverse perspectives.

If you missed Waldo’s splendid article, “Immigrant Muse: Sapphic Fragmentation in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha's Dictée, Hoa Nguyen's "After Sappho," and Vi Khi Nao's "Sapphở"“ in TAPA, go check it out.

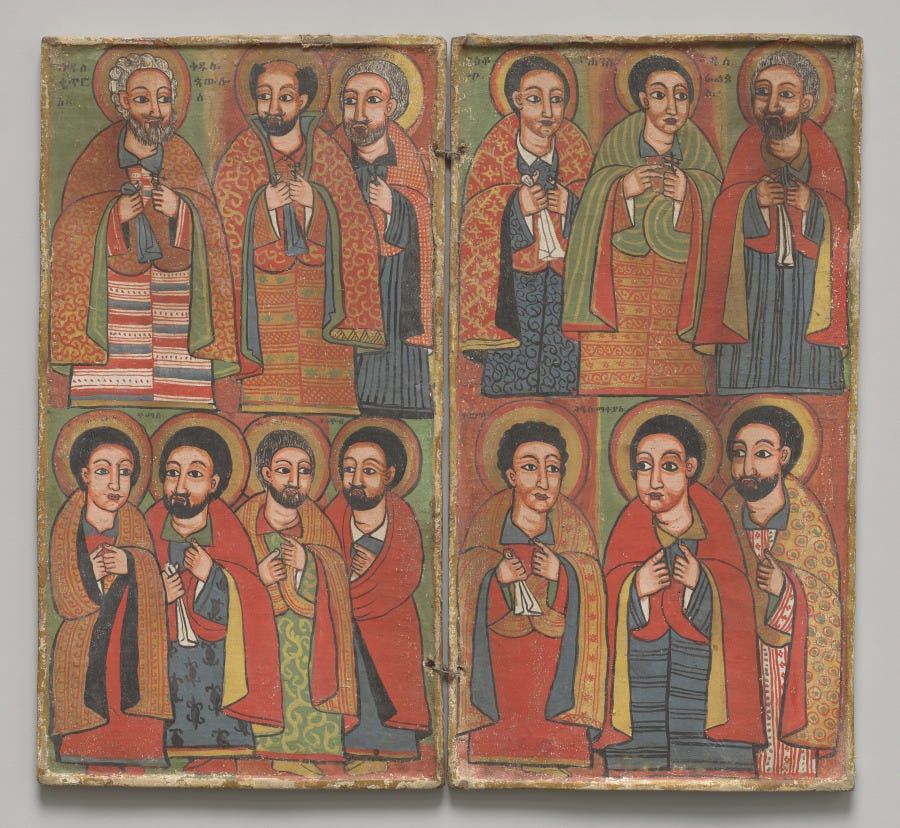

If you missed the epic Africa & Byzantium exhibition at the Met, you can now see it from April 13 until July 21, 2024 at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Living in the Midwest, I ponder pigs a fair amount. And as it turns out, my Wisconsin neighbor, Jewish law expert and electric guitar enthusiast Jordan Rosenblum, does too. In 2010, Rosenblum published a pivotal article on Jewish dietary restrictions: “Why Do You Refuse to Eat Pork?’’ Jews, Food, and Identity in Roman Palestine.” Now, his new book, Forbidden: A 3,000-Year History of Jews and the Pig, is available for preorder and out in October.

Though the Torah prohibits eating pig meat, it is not singled out more than other food prohibitions. Horses, rabbits, squirrels, and even vultures, while also not kosher, do not inspire the same level of revulsion for Jews as the pig. The pig has become an iconic symbol for people to signal their Jewishness, non-Jewishness, or rebellion from Judaism.

In the book, Rosenblum roots out all the pork-o-phobia over these thousands of years, all in an accessible and engaging read.

The book news is juicy this month. In June, papyrologist Brendan Haug has Garden of Egypt: Irrigation, Society, and the State in the Premodern Fayyum, coming out open access with Michigan Press. Also, we are thoroughly enjoying the new, open access Atlas of Contemporary Egypt, which has an intriguing chapter by Hala Bayoumi and Karine Bennafla on “Luxor: ancient heritage as an economic resource.” Egyptologist Monica Hanna will have a new book available for preorder in the summer called The Future of Egyptology.

If you too enjoy the lure of the arena, there is a new book edited by Sinclair W. Bell, Anne Berlan-Gallant, and Sylvain Forichon on spectacles in the ancient world, which questions the level and type of public access to the ancient games: Un public ou des publics ? La réception des spectacles dans le monde romain entre pluralité et unanimité. I am particularly stoked to read Barbara Dimde’s chapter on “Milites in caueā: On the Audiences of Military Amphitheaters.”

There is a great review of Josephine Crawley Quinn’s new How the World Made the West: a 4,000-year history in the Economist (open access version here). Quinn is currently at Oxford, but will join the faculty at University of Cambridge on January 1, 2025. She will be the first woman to hold the Professorship of Ancient History in the University.

At the linked open data Pleiades Project (a gazetteer of the Mediterranean world and beyond that geolocates and provides bibliography for over 43,999 ancient locations), there are a number of newly updated resources and citations, particularly within the Arabian peninsula and Ethiopia (e.g., Baitios and A(u)xoume). These maps also pair well with reading Helina Solomon Woldekiros’s new book, The Boundaries of Ancient Trade: kings, commoners, and the Aksumite salt trade of Ethiopia.

From Singapore to Ancient Egypt to Native America, foraging for food has a global and important history that is having a renaissance. This is particularly true for mushrooms, since we are now entering into an early season for the tasty fungi called morels. Before going out and doing your own ancient foraging assignment in class, the morel of the story may be to first check in with professional foragers and modern frumentatores like Alexis Nikole Nelson, or perhaps use a plant app to help you avoid ending up like poor Claudius. 🍄

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Greek and Roman Musical Studies Vol. 12 No. 1 (2024)

Asian Philosophy Vol. 34, No. 2 (2024)

The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Vol. 86, No. 2 (2024)

Avar Vol. 3 No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

DABIR (Digital Archive of Brief Notes & Iran Review) Vol. 9, No. 2 (2022) New Series

Synthesis Vol. 30 No. 2 (2023) #openaccess

Bibliotheca Orientalis Vol. 80, Nos. 3-4 (2023) NB Nathan Wasserman & Nimrod Madrer “Of Monkeys and Squirrels”

Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 143, No. 1 (2024)

Revue de Pédagogie des Langues Ancienne, Vol. 2 (2023-2024) #openaccess Langues anciennes et langues vivantes en contact

Latomus Vol. 82, No.4 2023

Classical Journal Vol. 119, No. 4 (2024) Plautus in the Heartland and Beyond: Washington University in St. Louis’ 1884 Rudens and its Context

Anatolica Vol. 49 (2023)

Early Medieval Europe Vol. 32, No. 2 (2024)

Classical Antiquity Vol. 43, No. 1 (2024)

Antiquity Vol. 98, No. 398 (2024)

Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus Vol. 22, No. 1 (2024) Jesus: A Life in Class Conflict

Recherches de Science Religieuse Vol. 112, No.2 (2024) Humanités numériques et théologie

Digital Scholarship in the Humanities Vol. 39, No. 1 (2024) NB Joey McCollum & Robert Turnbull “Using Bayesian phylogenetics to infer manuscript transmission history”

Public Lectures, Exhibitions, and Workshops

The American Council of Learned Societies last week announced they would pursue an expansion of their eligibility requirements for the ACLS Fellowship Program: “Starting this coming academic year, in the 2024-25 competition, the program will accept applications from eligible scholars across all career stages, from recent PhDs through senior scholars, working in every sector of the academy and beyond.”

On April 22, 2024, join Georgia Andreou for a webinar: “In the Name of ‘Heritage’ Gazan Archaeology Before and After October 2023.” It runs 12:00pm - 1:30pm EDT (11:00am - 12:30pm CDT) and is sponsored by the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World. Sign up here.

The SCORE research group at Hamburg announced that their online lecture series “Rethinking Social Contention” resumes next week on April 23, 2024. Ilkka Lindstedt will discuss his work on “Raiding and Warfare in Early Islamic Inscriptions.” The event will take place at 4:00 pm CEST on Zoom. In order to register for the talks, please send an email to score.aai@uni-hamburg.de.

On April 26, 2024 from 3:00-4:30pm ET, there is the Society of Ancient Medicine and Pharmacology’s Book Webinar with Rafael Rachel Neis and C. Michael Chin (moderated by Aileen R. Das). This webinar celebrates and discusses the publication of Rafael Rachel Neis' When a Human Gives Birth to a Raven: Rabbis and the Reproduction of Species (UC Press, 2023) and Catherine Mike Chin's Life: The Natural History of an Early Christian Universe (UC Press, 2024). The event, requires registration. Please register here.

A packed update full of fascinating avenues to explore. Thank you!