This week, ACLS President Joy Connolly discusses the value of the humanities and a better strategy for fighting for them. Then, using wasabi to preserve pigment on papyri, inscriptions on an eleventh century astrolabe, trans readings of the Odyssey, gender through the lens of Ancient Chinese medicine, what reading James Baldwin can teach Christians (and humanity) today, a workshop on ancient ‘Aithiopian’ figures from Greek myth, and much more.

Fighting for the Humanities by Joy Connolly

We are in a battle over the value of higher education in the United States. A major part of that battle is over its perceived purpose. If our goal as educators is more than offering credentials, we must do more than prepare students for jobs – and yet career readiness is how colleges and universities are pitching themselves to a skeptical public. As West Virginia University president E. Gordon Gee declared in his State of the University speech last March, hinting at the deep cuts to academic programs that were publicly announced six months later: putting students’ careers first “shines a light” on areas of study “that may no longer be relevant.”

That college-as-workforce-preparation narrative is winning over trustees, legislators, and public opinion. While the sciences aren’t immune to this repackaging, it’s doing the most damage to the humanities. So far none of the claims on offer about the value of the humanities (whether or not they fall in with the workforce prep mission) seems to be convincing the skeptics or even the neutrals. Some humanists reject case-making outright on the grounds that terms like “value” and “accountability” are incommensurable with humanistic study. This stance may be a gratifying way to let ourselves off the hook, but it doesn’t help the cause. And we need to fight harder and more effectively. Winter is already here.

Actually, it is heat we should be thinking about. In the 1990s, few of us could foresee the impact of climate change as well as digital communication – world-connecting, everyday-experience-altering phenomena that forever changed the meaning and the future of globalization. Yes, globalization reinforces structural inequality and limits freedom, and we’re right to resist these and other harms. But it has too much potential to be the professoriate’s punching bag. To preserve the planet for future generations, we need to cultivate fresh thinking across borders and differences on a global scale.

Instead of yielding higher education up to corporate capitalism, we must make the whole world our scholarly priority – and explain what we study and teach in those terms. We need to understand human beliefs, motivations, and the different ways we find and make meaning; we need to understand the full range of the world’s languages and identity-shaping experiences and memories; we need to cultivate care for the world, past, present, and future.

This is the value of humanistic inquiry, and it is both intrinsic and instrumental. We cannot take action on climate change or inequality or autocracy or any other of the world’s ills without talking to one another: we need to study languages and how to use them effectively. We can’t communicate without understanding one another’s histories, perspectives, values, and habits of thought in context: we need to study culture, history, politics, art, and philosophy.

We cannot save ourselves without these skills, capacities, and knowledge, as much as each one of us can absorb and put to use. If our objects of study – a Dogon sculpture, a passage from the Dao De Jing, a Roman aqueduct, a trace of Navajo oral history – seem small and their scope narrow, this scale is no different from the sciences, where grand insights and inventions are impossible without the work of tiny observations and small-bore analyses. If we’re willing to pay scientists to probe genes and atoms to cure diseases and design better fuels, we should be willing to pay for humanists to read texts and interpret material evidence. It’s all the work of survival.

To fulfill this mission, we need a new design for our studies. Scholars of the ancient past have a chance to lead the way.

In the United States and much of Europe, the study of the world’s ancient pasts is currently sharply divided by region and heavily slanted toward the study of ancient Greece and Rome and its neighbors. Major premodern cultures like India and China are given short shrift and entire continents shut out. The better path is to establish a new discipline that embraces the study of ancient cultures all over the world -- to institutionalize the vision of Pasts Imperfect, in fact. As the brilliant curator and art critic Okwui Enwesor did for the art world with his documenta11 and 2015 Venice Biennale All the World’s Futures, which strove to connect a highly disorganized, diverse world through art, we can draw a new map of the world’s pasts.

This new map will allow Western classical studies to shed the burden of its disciplinary history, so tightly bound up with European imperialism and racism. In conversation and collaboration with scholars of antiquity around the world, scholars will gain perspective, fresh questions, and a clearer-eyed purchase on Greece and Rome. Scholars working on regions outside the Mediterranean will secure an institutional home, freeing them from the isolated fight for funding in programs favoring modern or contemporary issues.

Recently we’ve seen efforts in departments of classical studies to include Egypt and the Near East. The quasi-mythic pull of Greece and Rome, though, means that this admirable move doesn’t go far enough. Studying ancient cultures in a global aggregate is our best bet to rewrite the antiquated master narrative of human history that is still told around the world, the one in which civilization began in Mesopotamia, traveled west to Egypt, and blossomed in Greece and Rome, which became the ancestor of democracy, freedom, selfhood, and law, not to mention philosophy, science, history, art, and literary studies. That narrative never encompassed the true story of human development and creative invention on our planet. It wasn’t designed to tell the truth.

By boldly embracing the whole world as the frame of ancient studies, we can finally set aside assertions of value that rest on shaky claims about the transmission of cultural heritage (“the West”). We can stop erasing entire cultures by calling the ancient Mediterranean “antiquity” or “the ancient world.” Specialization will be better balanced by breadth and scholars will direct more energy to dialogue outside their fields, transregional and transcultural studies, comparison, and collaboration.

Further Bibliography

Steven Mintz, “Why We Need the Humanities in Today’s Career-Focused World,” Inside Higher Ed (August 30, 2021). For all of his IHE columns, look here.

Martha C. Nussbaum, Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities - Updated Edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

Helen Small, The Value of the Humanities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

The National Humanities Alliance’ advocacy toolkit

Public Scholarship and a Global Antiquity

A newly published study looks at how wasabi can help preserve pigments on papyrus. As the authors note, “Wasabi has [already] displayed substantial fungicidal behavior for the disinfection of bio-deteriorated non-painted archaeological papyri.” The authors then conclude that it can also be used to help painted papyri and thus present “a green and cost-effective conservation approach for long-term preservation of painted archaeological papyri.”

In an open access article in the journal Nuncius, curator and historian of medieval Islam Federica Gigante has a new analysis of an eleventh century astrolabe originally from Al-Andalus with Arabic, Latin, and Hebrew inscriptions. The astrolabe is now in the collection of the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo in Verona, Italy. Gigante believes the rare device could have been made in Toledo, in a period when “it was a thriving centre of coexistence and cultural exchange between Muslim[s], Jews and Christians.”

In Hyperallergic, Nandini Pandey and Lauren Cook have a fantastic review of the new exhibition at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore: Ethiopia at the Crossroads, curated by Christine Sciacca. As they note, it brought together “220 artifacts spanning almost two millennia.” Through these objects, Ethiopia at the Crossroads “unfurls continuities between past and present across East Africa’s rich artistic traditions.”

“The show’s richest sections explore Ethiopia’s historical pluralism and engagements with other cultures within and beyond Africa. Coins of the Aksumite empire (3rd to 7th centuries CE), showcased against a photo-backdrop of Axum’s monumental stelae, proclaim ecumenical ambitions to rival the Roman empire.”

What does it mean to be proposed to with the same Homeric quotation? In MythTakes Donna Zuckerberg and Jackie Murray discuss their exes, the need for context when using a quotation to profess one’s love (specifically one pulled from Odyssey, book 6), trans readings of ancient texts, Artemis, and many other subjects.

The British Museum’s social media person likely had an intense meeting on Monday morning while discussing their Insta re-post over the weekend, which suggested ladies should go hang out at the new Legion: Life in the Roman Army exhibition in order to find men. Quite the dated suggestion.

Earlier this week, Byzantinist Foteini Kondyli gave a splendid lecture on “Inhabiting Byzantine Athens, Insights from the Athenian Agora Excavations Archives,” which you can watch below. Also check out the Inhabiting Byzantine Athens digital humanities project, which attempts to reconstruct the city between 300-1500 CE.

In a new article published in The Bulletin of the Jao Tsung-I Academy of Sinology, historian of the Han Dynasty Yunxin Li challenges constructions of gender by looking at medicine in Ancient China, starting from the 馬王堆帛書 (Mawangdui medical texts). Li concludes that “Feminists and postmodernists have challenged the constructions of gender on the basis of biological differences. Ancient Chinese medicine echoes this view of gender as non-binary.” Li is now working on a book manuscript tentatively titled “Eternal Scandal: The Inner Court and Politics in the Han Empire,” based on her dissertation.

A new grant from the Mellon Foundation will support the expansion of “Racing the Classics,” a program co-founded and led by Sasha-Mae Eccleston and Dan-el Padilla Peralta. Also note that on March 7, 2024, Johns Hopkins University is hosting the “Future of Ancient Race” conference as participants seek to “collaboratively build an open-access online resource (OER) in part thanks to current participants in [Nandini] Pandey’s Classics Research Lab, the Race in Antiquity Project (RAP).”

This Sunday, March 10th, a new series of the History of Philosophy without any Gaps podcast debuts: the History of Philosophy in China.

In February, PI contributor and historian of Late Antiquity Father Jarel Robinson-Brown spoke at St. Paul’s Cathedral about the life and writings of James Baldwin—and how Christians can use his writings to shape and envision a better future.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Syria Vol. 100 (2023) #openaccess

Les nouvelles de l'archéologie, no. 170 (2023) #openaccess Archéologie et photographie

Méthexis Vol. 36, No. 1 (2024) Part and Whole in Antiquity

ISAW Papers Vol. 22 (2022) #openaccess Re-Rolling the Past: Representations and Reinterpretations of Antiquity in Analog and Digital Games

Clotho Vol. 5 No. 2 (2023) #openaccess

Dead Sea Discoveries Vol. 31, No. 1 (2024)

Acta Archaeologica Lodziensia Vol. 69 (2023) #openaccess

Madrider Mitteilungen Vol. 64 (2023) #openaccess

Études et Travaux Institut des Cultures Méditerranéennes et Orientales de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences, Vol. 36 (2023) #openaccess

Dike - Rivista di Storia del Diritto Greco ed Ellenistico Vol. 26 (2023) #openaccess

History of Philosophy & Logical Analysis Vol. 26, No. 2 (2023) Now, Exaiphnēs, and the Present Moment in Ancient Philosophy

International Journal of the Classical Tradition Vol. 31, No.1 (2024)

History of Philosophy Quarterly Vol. 40, No. 4 (2023)

Mnemosyne Vol. 77 No. 2 (2024)

Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Bulletin Vol. 9 Nos. 1 & 2 (2023) #openaccess

Trends in Classics Vol. 15, No. 2 (2023) Greek Literary Papyri in Context

IPM Monthly: Medieval Philosophy Today Vol. 3, No. 2 (2024)

Phronesis Vol. 69, No. 1 (2024)

Bamboo and Silk Vol. 7, No. 1 (2024)

The Medieval Globe Vol. 9, No. 2 (2023) How to Ask in the Medieval World

Ploutarchos Vol. 20 (2023) #openaccess

Events, Exhibitions, and Online Workshops

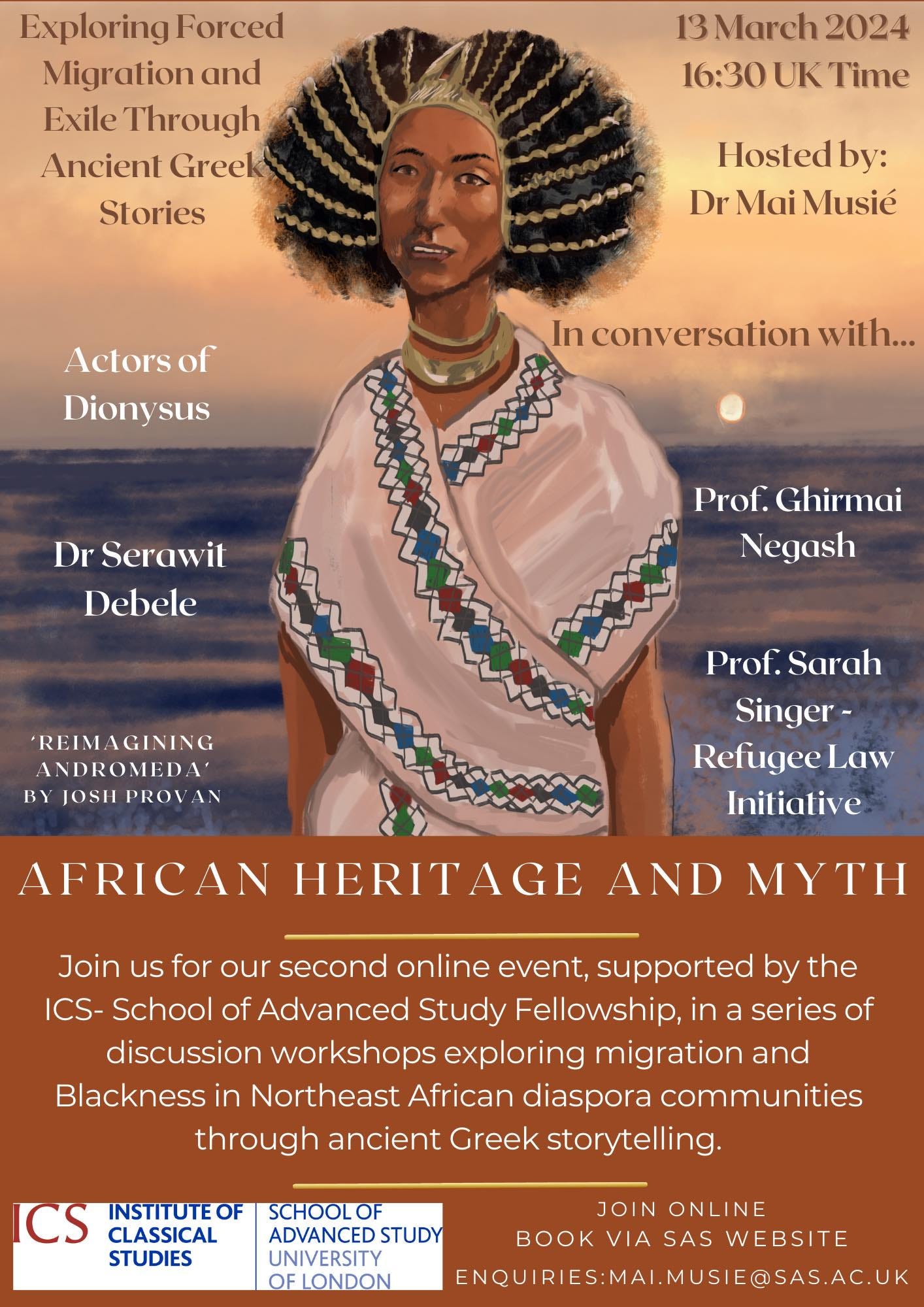

On March 13, 2024, 4:30PM - 6:00PM (UK Time) will be the second workshop supported by the ICS-School of Advanced Study Fellowship, in a series of discussion workshops exploring migration and Blackness in Northeast African diaspora communities through ancient Greek storytelling. This edition will explore: Modern dramatic performances of ancient ‘Aithiopian’ figures from Greek myth, the power of storytelling: oral and literary traditional, gender and marginality, perilous journeys: modern Ethiopian-Eritrean experiences of migration. Register here.

On March 27, 2024, Join the AIA for a lecture from Kisha Supernant on '“Finding the Children: Using Archaeology to Search for Unmarked Graves at Indian Residential School Sites in Canada” at 8pm ET online: “In May 2021, the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation in British Columbia, Canada, announced that 215 potential unmarked graves were located near the Kamloops Indian Residential School using ground-penetrating radar conducted by archaeologists…In this talk, Supernant provides an overview of how archaeologists have been working with Indigenous communities in Canada to locate potential grave sites and discuss the opportunities and challenges in this highly sensitive, deeply emotional work.” Register here.