Pasts Imperfect (3.6.25)

The Global Middle Ages, Translating Linear Elamite, Ancient Chinese Imitation Jade, Reconstructing the Lighthouse at Patara & More

This week, assistant professor of Arabic and History Rachel Schine discusses the risks, rewards, and intricacies of pursuing a Global Middle Ages (GMA). Then, glass imitation jade in ancient China, Dionysian frescoes emerge at Pompeii, the life of a Roman worker, translating Linear Elamite, the perils of DEI work in Classics, engaging with queer archives, an important documentary takes home an Academy Award, new ancient world journals, a talk on communal governance in the Mayan Kingdom of the K'iche' State, and much more.

Whose Global Middle Ages? by Rachel Schine

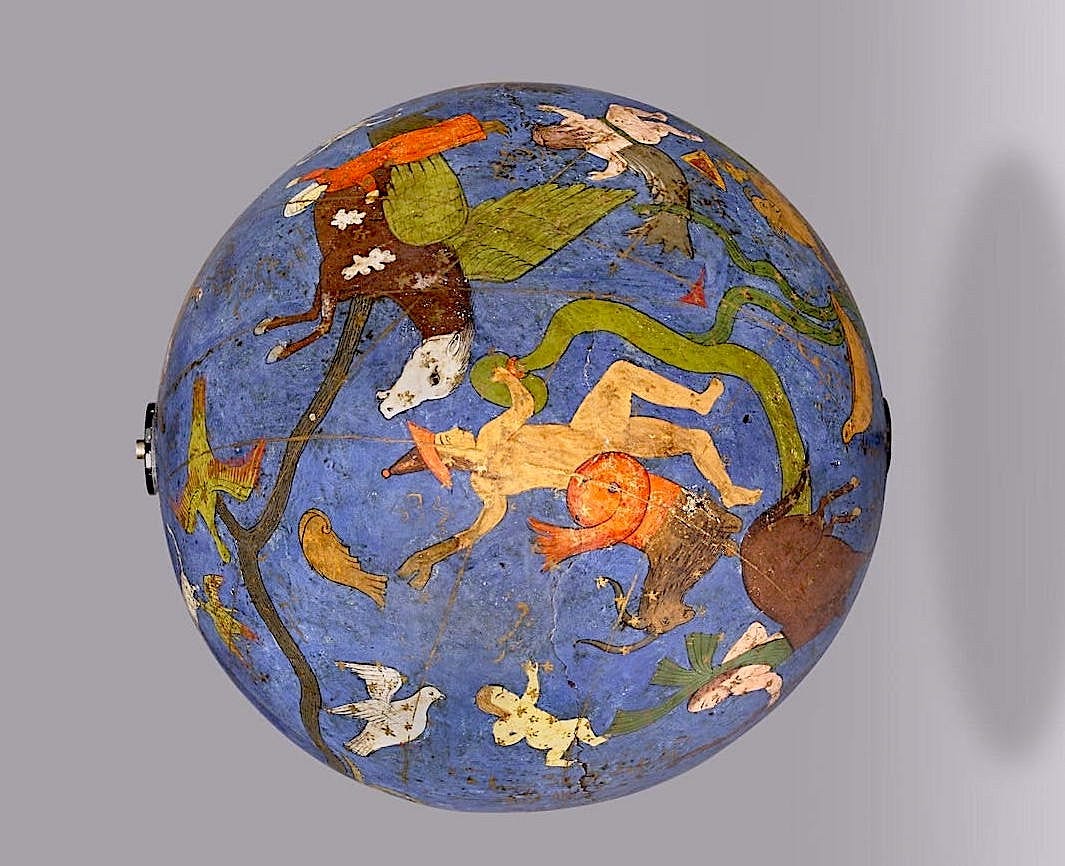

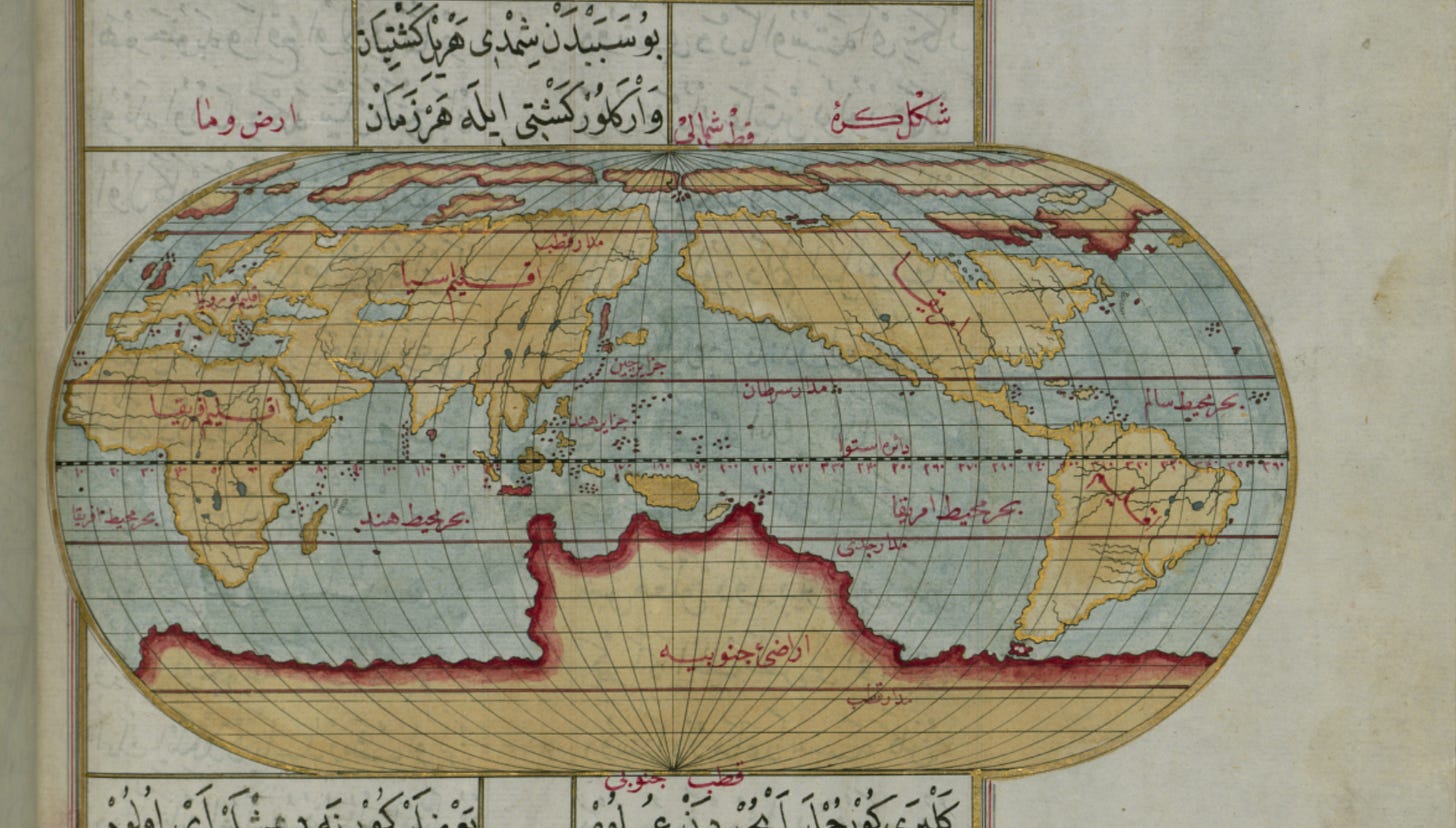

The Global Middle Ages has evolved over the past twenty years, particularly within the English-speaking academy. The term was coined by literature scholar Geraldine Heng in 2004 as a way of uncentering Europe from the Middle Ages (c. 500-1500 CE) and underscoring the interconnected nature of that world. What began as a pedagogically innovative movement to decolonize and diversify a single field has become a catchall for manifold efforts at academic reform. It is certainly commendable and useful to complicate the meaning and prominence of Europe in our narratives of the Middle Ages. But the “global” has now become a way to navigate budgetary austerity, a way to advocate for interdisciplinarity, a way to teach people who tend to assume “medieval literature” is mostly Beowulf a thing or two about Tang Chinese poetry, and a way to combat the nativist white nationalist uptake of a narrowly-construed medieval past in the public sphere, all at the same time. In other words, the Global Middle Ages is doing a lot.

In a recently published contribution to a roundtable on the paradigm’s utility for Islamic historians, I propose that the Global Middle Ages (GMA) may have jumped the shark. But can it get back on track?

I break my critique down into a few main concerns: the moral, the historiographical, and the institutional. These elements are mobilized in ways that blur the lines between them: historiographical projects are moralized in order to make them institutionally legible, and institutions frequently justify resourcing certain historical pursuits by using moral cover.

To pick apart the moral and historiographical claims of GMA projects, I looked to edited volumes, surveys, or special issues of journals that consciously brought together scholarship under the GMA framework and its synonyms (e.g. histories of “connectivity” and proto-“globalization”).

Much work of this kind is principally synthetic and secondarily analytical. It is driven by an interest in calling Europeanists’ attention to transregional dynamics that either suggest a more diversified premodern “West” or a more consequential (read: civilized, developed, or in one case “industrialized”) “rest” than the narratives of Western modernity would have us believe. To present this globality, GMA scholarship often extracts philological data translated by scholars working in non-Latinate languages but does not necessarily engage with the interpretative structures through which that data is made meaningful in its primary scholarly domain. This can reproduce the very Eurocentric approaches that the GMA aims to undermine by rendering work that extends beyond Western Europe a raw material for knowledge-production rather than a part of a dense apparatus of knowledge unto itself.

In many cases, the word “global” has become the newest byword for stating that non-(western)-(Christian)-(imperial)-(elite)-Europeans matter to European history, or that they should. And while this is an important statement to make, its invocation would seem to align medieval studies with the postcolonial critique of 40 years ago. When espoused as a polemical stance by scholars decrying their field’s festering dogmas, the global is therefore less a call to collaborate than to clean house. When espoused in conciliation to this critique, though, it cannot but be a paternalist gesture: how good of us Europeanists it is to allow the other peoples of the world to matter. And, our subjects mattering being a point of trite fact for people outside of Europeanist disciplinary arenas, scholars of Islamic or Asian or African or pre-Columbian American history meanwhile need not motivate their studies by declaring their globality. However, this lack of stake can be taken for under-theorization and used to rationalize the uneven terms on which GMA scholarship is taking shape.

The GMA’s assurgency of course has its own context and original motivations. Here I’ll stray a bit from the strict summary of my article for the sake of a broader point about how global pedagogical approaches evolved in other disciplines. In her book, The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism, intellectual historian Tomoko Masuzawa argues that world religions projects were spurred by an urgent investment in interfaith understanding to the end of never again becoming embroiled in a “world war.” And in regard to early “world civilizations” instruction, Kevin van Bladel contends in his article, “A Brief History of Islamic Civilization: From Its Genesis in the Late Nineteenth Century to Its Institutional Entrenchment,” that these courses grew out of scholars of the non-West seizing the opportunity conferred by Cold War cultural panic. And although Geraldine Heng coined the term “Global Middle Ages” in 2004, its continued rise since 2016 emblematizes an earnest and timely academic reaction to the near-simultaneous rise of Trumpism, a truly global pandemic, and a new international movement for Black lives anchored in the United States.

These are perhaps the most significant issues for our students and for us as teachers, but how is this response being captured by the institutions in which we are situated–institutions where the elite capture of identity politics has been identified in plenty of other domains? To that end, I considered job ads that expressed an interest in the candidate’s expertise in the GMA.

In part as an inevitability of their genre, job ads reduce the capacious ambitions of interdisciplinary exchange espoused in GMA publications down to the labor burden of the individual. And while cluster hires are a proven method for increasing a program’s diversity and scope, I have never seen a GMA cluster hire (but would love to be disproven). Almost all the ads seeking “global medievalists” were hosted by English departments, with a smattering in History and Art History. There are a few obvious reasons for this as well: English is where medieval literary studies have largely been historically situated. English departments are faring better than other premodern fields under increasingly austere academic conditions.

Other premodern fields have largely not taken up this discourse of the “global” for the above-mentioned reasons. But taken together, these incidental aspects of how singular academic hires are solicited paint a bleak picture of the global as a device for legitimating medieval studies’ traditional homes. GMA promises to cover an unprecedented range of regional, linguistic, and cultural areas within increasingly hostile conditions. We other premodernists must therefore be at pains to say—it simply can’t.

What might it look like to hone in on the “global” more effectively? Co-authorship rather than vague gestures to collaboration; theoretical engagement with the arguments of other fields rather than data-mining their translations; and encouraging graduate students working on Western European domains to pursue language and skills training appropriate to their aims to conduct transregional research are a start. This is a more “global” approach than simply rebranding or renaming medieval studies programs in anticipation of pitching to the “market.” Any of these approaches would go a long way towards making the global medieval salient for its profundity, and not just for its omnivorous breadth.

Global Antiquity and Public Humanities

In the journal Scientific Reports, Sai Huang, Ziyi Wang, and Junyi Zhu address “Research on glass imitation jade culture in the ancient Chinese Silk Road.” They look at “glass manufacturing technology from West Asia to China, especially after the Han Dynasty [206 BCE–220 CE].” What they found was that “glass imitation jade on the ancient Silk Road in China” grew and integrated techniques from foreign glassmakers along with indigenous glassmaking in China. And if you haven’t read it yet, make sure to check out the open access Ancient Glass Research along the Silk Road volume.

Pompeii continues to give us cinnabar fever dreams. Over at Hyperallergic, Rhea Nayyar covers the new Dionysian frescoes from a banquet hall in the House of Thiasus. Other recent archaeological finds include a “sunken villa” in Lake Fusaro near Baiae, the recent use of AI to reconstruct the over 2500 blocks that made up the Neronian-era Roman lighthouse at Patara (modern-day Turkey), the discovery of an ancient gold mining community at Aten (near Luxor, Egypt), and the unearthing of the earliest known section of the Great Wall of China in Guangli Village (Shandong Province). This section dates to the early Spring and Autumn Period (770 BCE–476 BCE) of the Western Zhou Dynasty, moving back the earliest date for the structure 300 years.

At the Society for Classical Studies blog, classicist Arum Park discusses “The Benefits and Costs of DEI Research in Classics.” She underscores that the “unique satisfaction of DEI work is also accompanied by unique distress.” A key example of this? When collecting data (published here) for TAPA’s special issue on “Race and Racism: Beyond the Spectacular',” her methods, approach, and even justification for the project were subject to intense scrutiny from those taking the survey. There are many risks for minoritized scholars doing this important work; risks that white scholars can take on and help alleviate.

Melissanthi Mahut joined Lexie Henning on the “Ancient Office Hours” podcast to discuss her work as the voice of Kassandra on Assassin’s Creed Odyssey. Also, the great Neville Morley has a fantastic, open access article on “Remaking Thucydides.” In it, he looks at “The ways in which Thucydides has been received, interpreted, and redeployed as a figure of authority and enduring relevance in the modern era.”

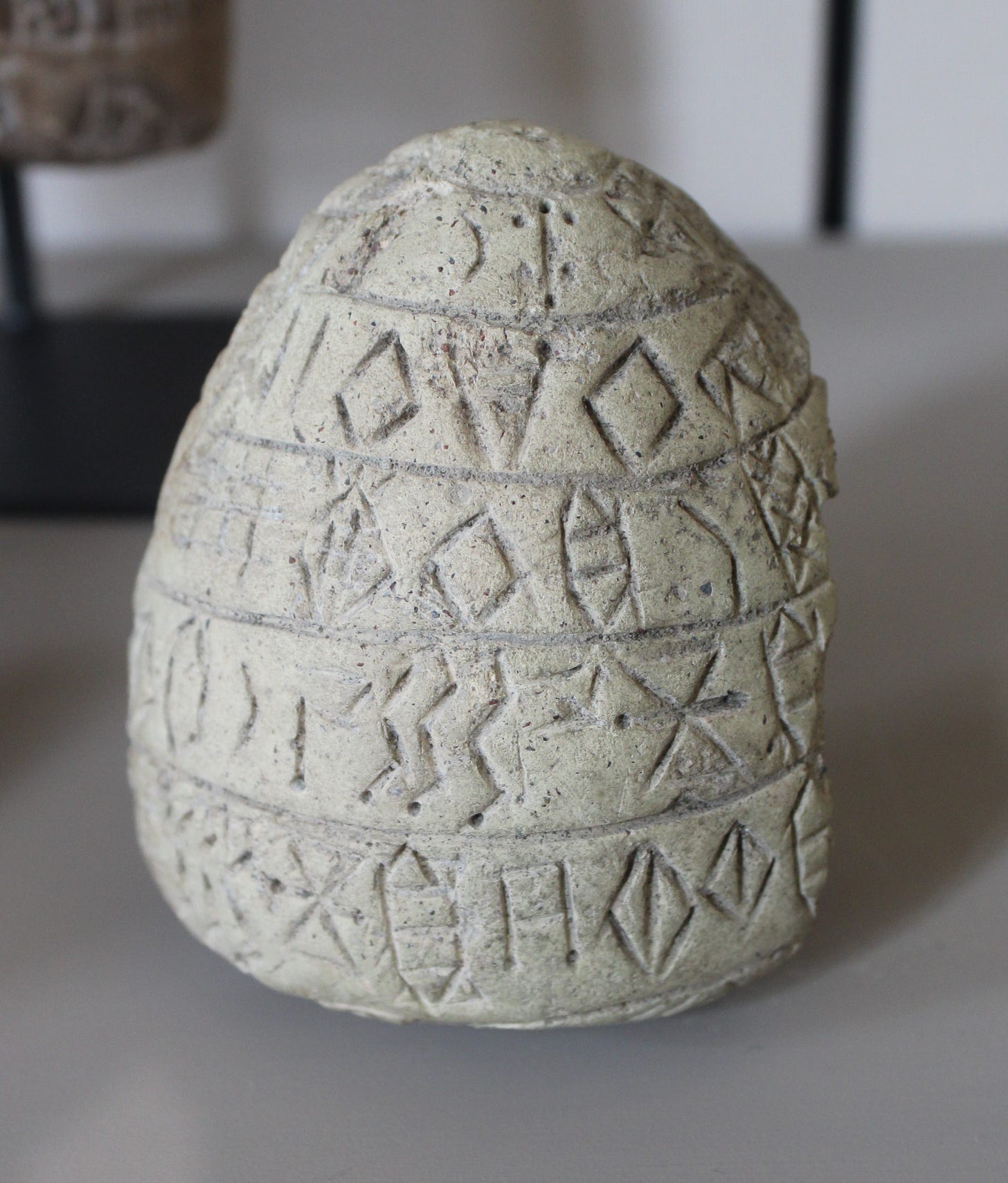

In the latest issue of the London Review of Books, contributing editor Tom Stevenson discusses “Beyond Mesopotamia,” on the deciphering of Linear Elamite. But the piece that moved me most was the new essay by poet and classicist Anne Carson. Starting with Catullus’ fragment 46 and touching on everything from painter Cy Twombly’s brushstrokes to taking up boxing to help her body fight Parkinson’s, Carson continues to amaze.

Archival work can be restorative work. Friend of PI and Africanist T.J. Tallie (he/they) is an Associate Professor of African History at USD. He is now the Lambda Archive’s Community Historian in residence, working on a project called: “‘Whose World, Whose Home?’: Black Queer Life in San Diego, 1988-2002.” As the story below recounts, Tallie has been uncovering and amplifying the lives of many activists from the San Diego area, particularly a Black lesbian hero named Marti Mackey.

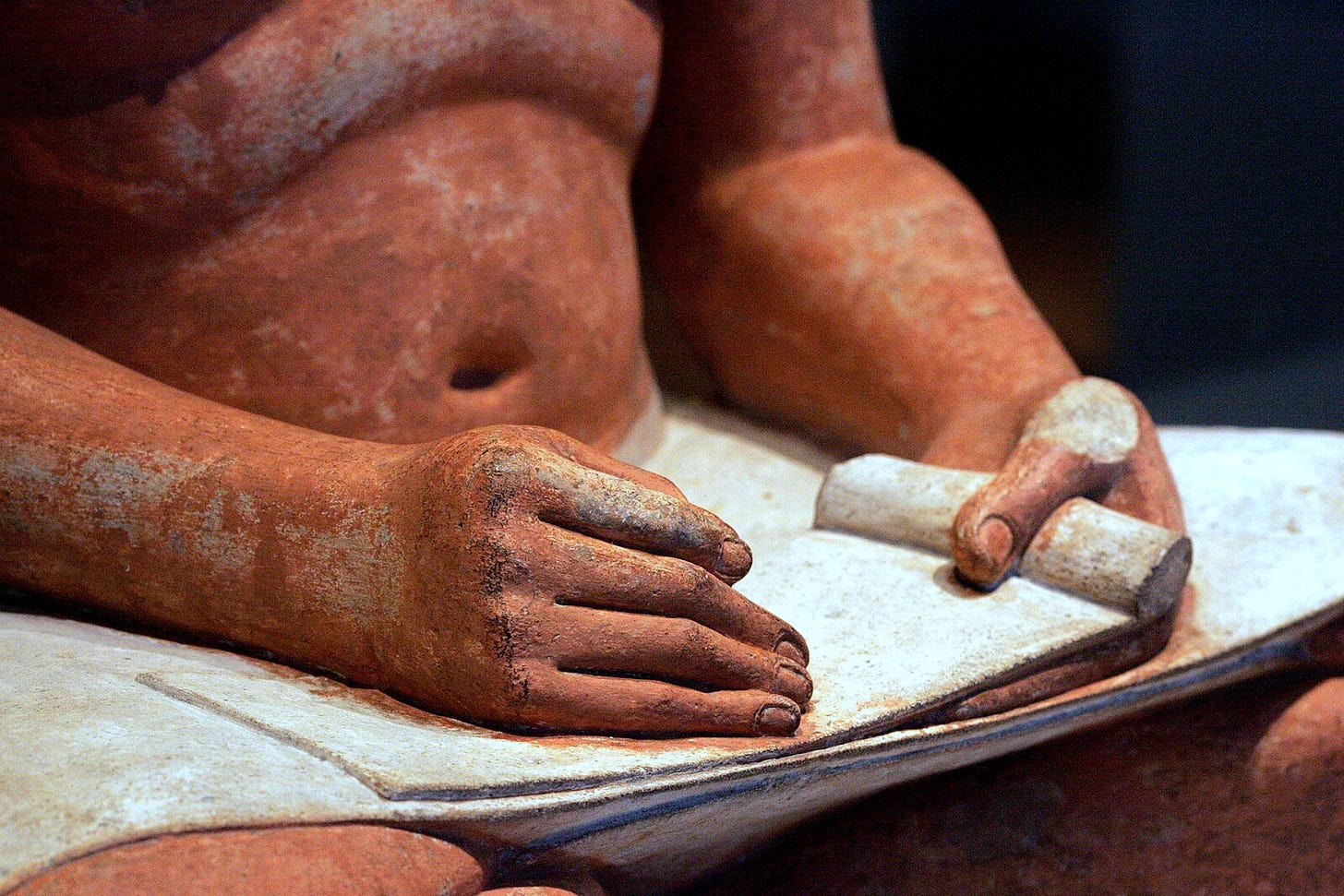

Over at Austrian newspaper Der Standard, they look at the “globalized medicinal market” that saw tradespeople and merchants bringing pharmacological products and ingredients into the Roman Empire. By looking at the use of malabathrum leaf and other ingredients for ancient eye ointments, the long distance trade routes that stretched far outside of Rome can be further uncovered. And at PRX’s The World, they speak to Del Maticic about “A day in the life of an ancient Roman worker.” It is a great listen and pairs well with the edited volume Working Lives in Ancient Rome.

Let us now turn to religion and the broader media. In the New York Times, arts and culture reporter Annie Aguiar discusses the rush to turn scripture into movie scripts following the success of the Jesus biopic series “The Chosen.” As she notes, many studios are hurrying to turn the Bible into streaming content: “Last year, Netflix signed a deal for faith-based entertainment that will begin with a modern-day retelling of the story of Ruth and Boaz. It also released “Mary,” a biopic about the mother of Jesus that included the Oscar winner Anthony Hopkins as King Herod.” One hopes they are calling some reputable religious studies scholars first? And in other news, the documentary “No Other Land,” a film about Palestinians fighting to save their West Bank community, Masafer Yatta, from being demolished, won the Oscar on Sunday. The acceptance speech is worth a listen and you can stream the doc in its entirety here.

And last but never least? This is an update to a neoclassical statue that we can really get behind. Who needs a suit when you’re standing up for liberty?

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Hermes Vol. 153, No. 1 (2025)

Aither No. 32 (2024) #openaccess

Axon Vol. 8 (2024) #openaccess

Arethusa Vol. 58, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage Vol. 18, No. 1 (2025)

Ariadne Suppl. No. 5 (2024) #openaccess KO-RO-NO-WE-SA. Proceedings of the 15th international colloquium on Mycenaean studies

Classical World Vol. 118, No. 2 (2025)

Journal of Archaeological Science Vol. 176 (2025)

Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie Vol. 107, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess NB Sylvain Delcomminette “Idealism and Greek Philosophy: What Natorp Saw and Burnyeat Missed”

Clotho Vol. 6 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess Anna Baranek & Elżbieta Olechowska “KAOS, Not ‘a Soap with Unusual Names’?”

International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing Vol. 19, No. 1 (2025)

Vivarium Vol. 63, No. 1 (2025)

Erudition and the Republic of Letters Vol. 10, No. 1 (2025)

Bulletin for Biblical Research Vol. 34, No. 3 (2024)

Anuario de Estudios Medievales Vol. 54 No. 1 (2024) #openaccess Orígenes del humanismo castellano en la corte de Juan II: historia, poesía y narraciones cortesanas

Journal for the Study of the New Testament Vol. 47, No. 3 (2025) Creation

Religion in the Roman Empire Vol. 10, No. 3 (2024) Imperial Religion versus Local Beliefs. Case Studies from the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa

Studies in Late Antiquity Vol. 9, No. 1 (2025)

Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Vol. 64, No. 2 (2024)

Vigiliae Christianae Vol. 79, No. 2 (2025)

Dao Vol. 24, No. 1 (2025) NB Daniel Canaris “State of the Field Report XV: Contemporary Chinese Studies of the Scholastic-Aristotelian Soul in Late-Ming and Early-Qing China”

Old World Vol. 5, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess De-Constructing Nubia

Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology Vol. 11, No 4 (2024) #openaccess NBAntonio Ruiz Sanchez, Sebastián Uribe Rodriguez "The Giant's Trail: Mobility and Exchange of Whales and Their By-Products in Antiquity (1st Century BC-5th Century AD)"

Classical Journal Vol. 120, No. 3 (2025)

Britannia Vol. 55 (2024)

Le Muséon Vol. 137, Nos. 3-4 (2024)

Gnosis Vol. 10, No. 1 (2025)

Arabic Sciences and Philosophy Vol. 35, No. 1 (2025)

Indo-Iranian Journal Vol. 68, No. 1 (2025)

Giornale Italiano di Filologia Vol. 76 (2024)

Events, Workshops, and Exhibitions

Thursday, March 6th, from 5:00-6:30 pm UK time (12 pm ET), classicist Cora Beth Fraser will be in person at University of Leeds and online via Teams for a seminar on “Minotaurs, monstering, and the representation of autism in popular culture.” You can find Microsoft Teams joining info here.

Over at the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA), they are hosting a “Society Sunday” on March 9th at 12:00 PM. It includes “a virtual presentation and Q&A with Iyaxel Cojtí Ren presenting ‘Communal Government and Forms of Dependency in the K'iche' State.’” As they note, “in the Maya highlands during the Late Postclassic period (1250-1524 CE), the K'iche' created an expansive state able to subdue various nations and form a network of dependent polities. You can sign up here.

On March 13th at 6:30 pm CET (12:30 PM EST) Irina Dumitrescu (University of Bonn) will lecture on 'The Medieval Roots of Celebrity' at the Centre d’Études Médiévales Anglaises - Sorbonne Université and online.`