Pasts Imperfect (3.6.23)

The Food History of Purim, Caesar's Spikes, Bamiyan after Bamiyan, and More

This week, Jordan Rosenblum discusses the food traditions surrounding Purim. Next, Javal Coleman answers the question: “What is it like to be the only Black person in your department?” Then, archaeologists find evidence for the wooden spikes noted by the likes of Julius Caesar, a lecture looks at the tales of the “lost Torah,” a new edited volume questions the “discovery” of the books of Enoch, new antiquity journals, upcoming public lectures, and more.

Recovering Purim, Jewish Food History, and Ishtar by Jordan Rosenblum

The Jewish holiday of Purim begins tonight. The festival celebrates Jews being saved from extermination within the Persian Empire, as recounted in the Book of Esther. If King Ahasuerus is the Persian king Xerxes, these events might be dated to 483-473 BCE, although this is uncertain. Food is just one way Jews celebrate and commemorate the holiday. Hamantaschen, the plural of hamantasch, refers to “a filled pastry shaped in a triangle.” [1] Gil Marks, an Orthodox Rabbi, chef, and Jewish food historian, notes that this cookie has medieval Teutonic origins and that, based on similarities between the German word for the poppy seed version, mohntasche, meaning “poppy seed pocket,” German Jews came to refer to this pastry as hamantasch, meaning “Haman’s pockets.”

This etymology makes sense. Haman is the villain in Esther, the biblical book that forms the basis for Purim. And the Hebrew name Haman, pronounced in some Yiddish dialects as Hamohn, sounds a lot like mohn – German for “poppy seed.” The biblical villain Haman is never specifically referred to as having pockets. Nor is he described as wearing a hat, triangular or otherwise, which is another folk-reason given for the shape of the cookie. And, while he presumably had ears, despite the fact that the modern Hebrew name for hamantaschen is oznei Haman, meaning “Haman’s ears,” which also refers to another sweet treat associated with Purim of either Spanish or Italian origin, the book of Esther never mentions Haman’s ears.

While Marks’ origin story for hamantaschen is the standard account that appears in newspaper and magazine stories each year around Purim, it ignores a much longer history in which triangular pastries are associated with the biblical heroine Esther. To learn this scandalous story, we need to return to the Queen of Heaven.

Remember that baking cakes to the Queen of Heaven was a practice that both greatly angered God and was primarily performed by women. Ancient rituals performed by women are often interpreted as fertility rites. While there are good reasons to not reduce every practice performed by ancient women to a single, essentialist, and gendered model, in this case there is strong evidence in support of understanding baking cakes to the Queen of Heaven as a fertility ritual.

Here’s why: first, the “Queen of Heaven” is almost certainly the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar, who is referred to by the same title in Akkadian texts. Second, once we accept Ishtar as the Queen of Heaven, we must consider the fact that Ishtar is associated with a fertility cult, in which women play a central role. Third, as part of devotion to Ishtar, there was a common practice of baking cakes to her. Fourth, in a related point, the word used for “cakes” in those two passages in Jeremiah – the Hebrew kavvanim – appears nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible; it only is used to refer to baked goods for the Queen of Heaven. Kavvanim is a loan word from the Akkadian kamānu, which is a sacrificial cake sweetened with honey and figs; and we have several attestations of kamānu being offered to Ishtar.

So the Queen of Heaven is Ishtar. What does that have to do with hamantaschen? First, the name Esther likely derives from the Akkadian Ishtar. Thus, the heroine of Purim has Ishtar for a name. Second, there is a common ancient practice of baking and ingesting sweet cakes as part of fertility rituals. These cakes are usually triangular in shape, so as to represent female external genitalia. For example, the ancient Greek Thesmophoria festival involved offering such cakes to the goddesses Demeter and Persephone. The basic concept is that by creating and then ingesting sweet cakes shaped like a pubic triangle, the consumer embodies fertility and thus is able to conceive. Thus, long before medieval German Jews encountered the mohntasche, there was a history of associating Esther with the consumption of triangular pastry.

In connecting German triangular pastry with Purim, medieval Jews likely were not aware of the scandalous past embodied in their poppy seed pocket. They certainly did not imagine their tasty treat as connected to a biblical practice that God decries. While for Jeremiah, it was a controversy, for medieval German Jews, it was merely a cookie.

[1] Gil Marks, Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, 248 (and in general, see pp. 248-250).

Further Reading on the History of Purim:

Milvia Bollati, Flora Cassen, and Marc Michael Epstein, with introduction by Christopher de Hamel, The Lombard Haggadah (Les Enluminures, 2019).

Catherine Bonesho, “The Jewish Holiday of Purim in the Late Roman Empire,” The SCS Blog (February 26, 2018).

Jonathan Homrighausen, “Esther Reenacted in Ritual: Esther 5:1-8,” The Visual Commentary on Scripture.

Adam Silverstein, “What can pre-modern Muslims tell us about the Hebrew Bible?” Ancient Jew Review (March 21, 2019).

Ilana Tahan, “The Book of Esther and the Jewish Festival Purim,” The British Library Blog (March 9, 2017).

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

On the SCS blog, Javal Coleman discusses his experiences as the only Black graduate student in his graduate program. As he concludes: it is time for change within the field of Classics.

The important and controversial African American Classicist Frank Snowden, Jr., concluded in his book Blacks in Antiquity, “The Greeks and Romans counted black peoples in.” And while that statement has stirred much debate over the last several decades, it is clear that, when it comes to the field of Classics itself, Black people are still not counted in. This must change. After all this is our field, too…right?

At Live Science, Kristina Killgrove digs into the new discovery at Bad Ems, within Germany’s Rhineland, of wooden defensive spikes. This ancient “barbed wire” is also mentioned by Julius Caesar. This is the first intact excavation of the technology:

This year, the student team led by Frederic Auth unearthed the preserved wooden spikes in the damp soil of Blöskopf Hill, which held a second recently discovered Roman camp 1.3 miles (2 kilometers) away from the first fort. The team also found a coin from A.D. 43, proving that the two forts significantly pre-dated a larger system of fortifications known as the "limes" that was constructed in A.D. 110.

In other archaeological news, a 2400-year-old ancient Chinese flush toilet was discovered in the ruins of Yueyang City. In Sudan, sandstone blocks with hieroglyphs have been unearthed at Old Dongola dating to the 25th dynasty of Egypt (747-656 BCE), which was a Nubian line of Pharaohs that ruled Egypt.

Until April 1, 2023, the University of New Hampshire’s Museum of Art (MOA) has a new exhibition call “Myths Retold: Paintings by Rosemarie Beck.” As the museum notes, “The paintings and embroideries in this exhibition draw from sources such as, Sophocles’ “Antigone” (441 BCE), Euripides’ “Hippolytus” (428 BCE), and Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” (1611 CE). Another major source was Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 CE), which was also a primary source for myths during the Renaissance.” And the labels themselves are written by students in Paul Robertson’s Advanced Mythology class (CLAS 601).

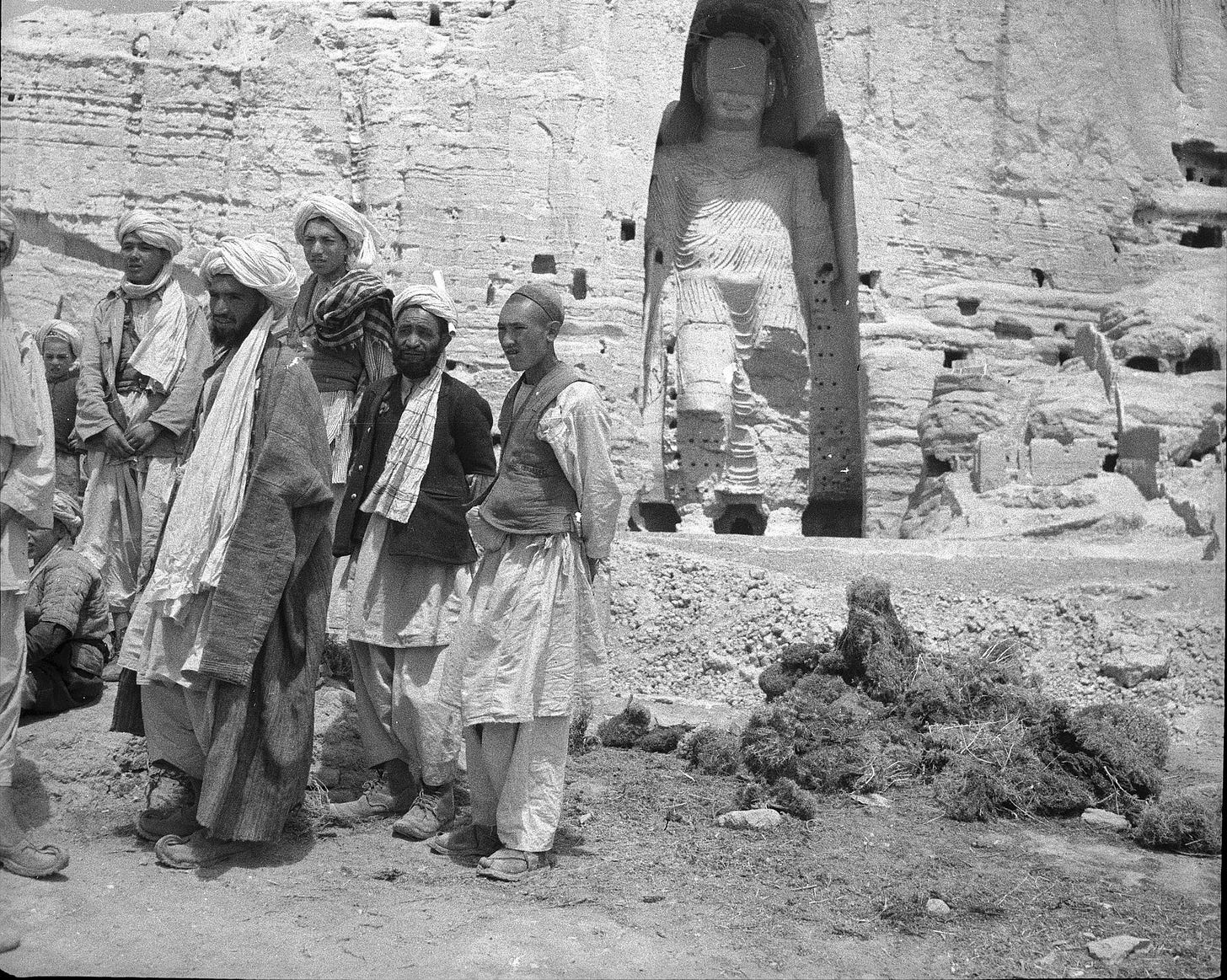

Over at Kabul Now, Llewelyn Morgan discusses the manipulation of ancient cultural heritage sites by modern politicians. He questions our reverence for antiquities and archaeological sites (and tales of their destruction) over human lives. Often, he notes, we give more attention to the decimation of a site than to those living and dying in war zones. He compares the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001 with the fanfare around Russia’s Mariinsky Theatre playing a surprise concert in ancient Palmyra in May of 2016, not long after Russian airstrikes helped extricate Islamic State militants from the site. In doing so, Putin helped to launder Bashar al-Assad’s own actions by using a classical currency:

The destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas dominated international news in a way that, for instance, the Taliban’s brutal treatment of the local population had not. Bamiyan, not unlike Putin’s extravaganza in Palmyra, was a media-conscious performance…The concert at Palmyra was an exercise in laundering Assad’s brutality (and Putin’s support for it) in a currency all-too acceptable to the wider world, classical music in a classical theatre.

In late January, Eva Mroczek, the incoming Simon and Riva Spatz Chair in Jewish Studies at Dalhousie University, delivered the inaugural lecture on “The Myth of the Lost Torah.” Mroczek asks what the stories of lost Jewish texts such as those desecrated by the Nazis might able to tell us about Jewish loss and living in the midst of catastrophe. She also inquires as to whether these stories can perhaps tell us something more: about preservation, repair, and what can be saved.

In the “Historical Essays” newsletter (and also see Reed’s essay at AJR), Ariel Hessayon, Annette Yoshiko Reed, and Gabriele Boccaccini discuss their new edited volume, Rediscovering Enoch? The Antediluvian Past from the Fifteenth to Nineteenth Centuries. In it, the editors and authors question the myths and marvelous tales of discovery that often surround manuscripts, particularly the books of Enoch.

The books of Enoch were among the long-lost heritage of ancient Judaism recovered in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. What they told of fallen angels, demons, the origins of evil, and the end of the world was popular among ancient Jews, including the first followers of Jesus, and Enochic books were even quoted by Jude and defended by early Christians like Tertullian. Yet the very apocalypticism that made them appealing in the Second Temple period (538 BCE-70 CE) caused their rejection by Rabbis in the second century and by Church Fathers like Athanasius and Augustine in the fourth and fifth. As a result, these writings virtually disappeared from historical view until James Bruce’s 1773 discovery of manuscripts of 1 Enoch in Ethiopia. Bruce’s discovery ushered in a new era of scholarship, marked by the recovery of forgotten forms of apocalyptic thought from Second Temple Judaism and the recognition of their influence on the origins of Christianity.

Or, at least, this is the tale that is conventionally told. But is it accurate? What was known before Bruce, and where?

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib)

Aethiopica Vol. 25 (2022) #openaccess

Journal of Semitic Studies Vol. 68, No.1 (2023)

Journal of Latin Linguistics Vol. 21, No. 2 (2022)

Akroterion Vol. 67 (2022) #openaccess

Near Eastern Archaeology Vol. 86, No. 1 (2023)

Études et Travaux Vol. 25 (2022) #openaccess NB Wojciech Ejsmond & Marzena Ożarek-Szilke “The Collection of Egyptian Mummies of the University of Warsaw and their Role in the ‘Prehistory’ of Polish Egyptology”

Essays in Medieval Studies Vol. 36 (2022) The Medieval Present

Classical Journal Vol. 118, No. 3 (2023)

Clotho Vol. 4 No. 2 (2022) #openaccess A Proletarian Classics: The Relationship between Ancient Greek and Roman Culture and World Communism from 1917

Ancient Philosophy Vol. 43, No. 1 (2023) NB Freya Möbus “Can Flogging Make Us Less Ignorant?: Socrates on Bodily Punishment”

Codex Revista de Estudos Clássicos Vol. 10, No. 2 (2022) #openaccess

Upcoming Public Lectures

On March 8, 2023, ancient historians Carlos Noreña and Nicholas Purcell discuss “Encounters in the Classical Mediterranean World.” Noreña will be speaking on "Romanization 3.0: Power, Infrastructure, Scale" and Purcell will address “Romans in Residence - and the Mediterranean which resulted” in this panel for ISAW-NYU. This event will take place online. Registration is required and can be made here.

On Thursday, March 9, 2023 at 2:00 pm GMT at the University of Oxford, Monica Hanna will be speaking on “Restitution of Knowledge: The Rosetta Stone and Egypt’s Estranged Heritage.” The lecture “will deconstruct the different notions and claims of the British Museum and indigenous Egyptians today in relation to the colonialist imperialist past and post-colonialist present.” Hear more about Hanna’s work here:

Ancient historian Evan Jewell will speak on “Transphobia and the trans* man in the tribas” on Thursday, March 9, 2023 at 5:00-6:30pm GMT. “The seminar will take place both in person in PG21, Pemberton Building, Palace Green, Durham (no registration required), and online.” To receive the Zoom link, please register here.

The Silk Roads Programme at King’s College, Cambridge has a number of upcoming events. On Friday, March 10, 2023 at 2:00 pm GMT, Catherine Alexander will speak on “Ownership and Identity in Central Asia: The Case of Aisha Bibi Mausoleum in Kazakhstan” and on March 17, 2023 at 2:00 pm GMT, Edward Lemon will discuss “China and Russia’s Relations with Central Asia: A Critical Approach.” Register here.

On March 27, 2023, at 5:00pm CDT | 6:00pm EDT, join the CHS, the Kosmos Society, and Out of Chaos Theatre for a performance of Sophocles' Electra! The event will take place in the University of Illinois-Chicago’s East Campus in Lecture Center A1. Contact Krishni Burns (ksburns@uic.edu) for more information. It will also be live streamed to the CHS YouTube Channel.