Pasts Imperfect (3.21.24)

Reimagining Pastoral Poetry, Have Cacao Will Travel, & New Historical Fiction

This week, members of Tori Lee’s seminar on pastoral poetry at Boston University take over the newsletter to chat about pastoral reception. Then, archaeologists of prehispanic South America shed light on the movement and use of cacao from more than 5,000 years ago; Cleopatra with the venerable Shelley Haley; more reception and historical fiction by novelist Oyin Sangoyomi; and a new award from the Women’s Classical Caucus. Read on, and don’t forget to pitch us your freshest baked ideas about global antiquity.

Displaced Pastoral Fantasy: Reception in Tomás António Gonzaga’s Marília de Dirceu, Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, and Cottagecore by Lauren Brown, Allison Jodoin, and Matheus Ely Pessoa

Reception studies allow us to approach ancient texts through interdisciplinary lenses and explore issues across a wide variety of regions and times. As part of Dr. Tori Lee’s graduate seminar on pastoral poetry at Boston University this semester, we have been presenting on and discussing receptions of pastoral beyond antiquity. The following examines the reception of ancient pastoral poetry.

As a whole, we have seen that pastoral, even in reception, generally involves an idealization of distant regions and a blurred past. Matheus Ely Pessoa turns to Tomás António Gonzaga’s Marília de Dirceu (“Dirceu’s Marília”), a Luso-Brazilian work written at the end of the eighteenth century that plays with the boundaries between the two continents. Allison Jodoin jumps ahead about two hundred years and examines pastoral reception in Tom Stoppard’s 1993 English play, Arcadia. Finally, Lauren Brown investigates pastoral elements of the contemporary #cottagecore aesthetic. Perhaps, by looking at the distant Mediterranean past through the lenses of those closer to us in time, we might be able to have a better grasp of ancient literature altogether and its influence throughout the centuries.

Arcadism in Colonial Brazil by Matheus Ely Pessoa

Looking back at my high school years in Brazil, I must admit that literature classes on authors prior to the nineteenth century were not really my cup of tea. Now, as a Classics PhD student delving into Vergil’s Eclogues this semester, I am taking this opportunity to revisit some literary works with fresh eyes and a new perspective—with special attention to the pastoral poetry written during the eighteenth-century Neoclassicist (or Arcadist) movement.

One of these authors is Luso-Brazilian poet Tomás António Gonzaga, author of a collection of “lyres” known as Marília de Dirceu. Throughout the book, Gonzaga—under his pen name, Dirceu—constantly addresses the young shepherd Marília and declares his love for her, while surrounding his characters with bucolic elements inspired by Greco-Roman pastoral poetry. In its opening lines, we read: “I, Marília, am not some cowherd / Who lives to keep someone else’s cattle . . . / I own the farm on which I live” (Part I, First Lyre, my own translation). This very first lyre, as Trevizam (2011) argues, mirrors Vergil’s Second Eclogue thematically, rhetorically, and linguistically, as Dirceu longs for the unrequited—or unattainable—love of Marília (just as Corydon for Alexis), praises her beauty, and boasts about his own qualities as means of impressing his loved one.

However, the similarities between both poems become more striking as we contemplate Gonzaga’s lyres against their own historical context. Although born in Portugal, Gonzaga moved to Brazil early in life and made a living in public administration. By writing pastoral poetry in South America, linking it directly to Vergil from the outset, and making use of typical Mediterranean elements in his bucolic universe, Marília de Dirceu manages to expand the European ties with the ancient world by dislocating cypresses, oaks, sheep, and lions (none of which are native to Brazil) over the Atlantic Ocean to the “New World”—where these elements serve the rhetorical purpose of fostering the bourgeois fantasy of a good life in the country.

Pastoral (A/I)llusion in Arcadia by Allison Jodoin

Tom Stoppard sets Arcadia in the English countryside in two different time periods: 1809 and the present day. At the risk of oversimplifying a complex play, in 1809, a young man, Septimus, mentors the young (and very clever) Thomasina. In the present day, Hannah and Bernard research the authors and individuals of the past. A single turtle (alternately named Plautus or Lightning) cements the connection between the two periods. When I was an undergraduate student at the University of Vermont, I was lucky enough to stage manage a production of Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia (with a live turtle!). I loved the way he divided the play into periods and how they were intricately connected. Since then, I always dreamed of having the opportunity to connect this classic play to Vergil’s Eclogues. Stoppard’s presentation of academia in this present feels so grounding for someone in the same position now.

Arcadia itself is a work of reception. The title refers both to 17th century Italian painter Guercino’s Et in Arcadia Ego as well as to the Arcadia of Vergil’s Eclogues. Guercino’s painting juxtaposes two shepherds in a peaceful landscape with a skull, highlighting how violence, death, and loss are nestled in a bucolic landscape. Stoppard’s Arcadia conceals a similar horror. While the beginning of the play embraces the pastoral ideal of peace and intellectual contemplation (often in terms of Newtonian physics, much like Vergil’s use of Lucretius), Thomasina’s and Septimus’ fates contrast this halcyon image. Thomasina dies in a house fire. Crushed by this loss, Septimus becomes a hermit. Nevertheless, the play ends with Thomasina and Septimus and Hannah and her lover dancing. Arcadia’s image of the pastoral world both begins and ends in serene moments of peace, but also allows the audience and the characters of the present to discover death and pain in the past.

Reception of the Pastoral Aesthetic in #Cottagecore by Lauren Brown

I pride myself, perhaps hubristically, on my eye for interior design and my thrift. As someone living outside of Boston, cottagecore is a trend that has appealed to me. Cottagecore, an aesthetic that embraces a return to nature, self-reliance, handmade wares, and anti-consumerism, gained popularity on social media during the turbulent year of 2020. The aesthetic idealizes old rural life and a withdrawal from the overstimulation of modern society. However, the aesthetic fails its ideals in a few ways:

Due to cottagecore’s (paradoxical) popularity on social media, the aesthetic has become commercialized in a way that undermines its ideals. You can obviously still thrift certain decor pieces, but companies have begun selling items that fit the aesthetic brand-new, and often at high prices (See The Other Aesthetic for cottagecore items sold brand-new, and Anthropologie for this $998 chair).

Cottagecore’s emphasis on handmade goods means that you would typically need a lot of time and/or money to obtain such goods.

Cottagecore is nostalgic for a non-existent, idealized past and ignores the negative aspects of the past.

The ancient pastoral aesthetic likewise features several handmade goods – such as wooden cups (e.g. Verg. Ec. 3.32-43) and pipes (Verg. Ec. 2.32-3) – and embraces country landscapes as an escape from the city. Furthermore, ancient pastoral, through its distant and temporally ambiguous settings, idealizes a non-existent past while obscuring the hard labor and cruel treatment of enslaved shepherds (Leigh 2016).

Ancient pastoral poetry, however, does have some awareness of its fantastical elements. The references to land confiscations throughout Vergil’s Eclogues reflect the difficulty of country life, and, as Leach (2021) argues, the Romans would have been aware, from reading Polybius, that the gleam of Arcadia was a fiction. Nevertheless, both the aesthetics of ancient pastoral and cottagecore seem to appeal to a desire for an escape from a turbulent present through a romanticized return to nature and idealization of the old.

Conclusion

Even now, the beautiful landscape of the pastoral world conceals a negative side. In Marília de Dirceu, Gonzaga props up the ideal life in the “New World” with impossible features. Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, although set in a charming English estate, hides death and a complete withdrawal from society. In the 21st century, the cottagecore aesthetic has followed Vergil, Gonzaga, and Stoppard in this tradition by commodifying simplicity. What the pastoral motif can teach us now is to look beneath the marketing of a perfect landscape and to be aware of its fictitious elements.

Sources:

Gonzaga, Tomás A. 2013. Marília de Dirceu. São Paulo: Editora DCL.

Leach, Eleanor. 2021. “Arcadia and the Roman Imagination.” In Myers, Micah Young and Erika

Zimmermann Damer, Erika, ed., Travel, Geography, and Empire in Latin Poetry. London: Routledge.

Leigh, Matthew. 2016. “Vergil’s Second Eclogue and the Class Struggle.” Classical Philology 111:406-433.

O’ Luanaigh. Robin. “Co-opting Cottagecore: Pastoral Aesthetics in Reactionary and Extremist Movements.” Global Network on Extremism and Technology. May 19 2023.

Stoppard, Tom. Arcadia. Faber & Faber, 1993.

Trevizam, Matheus. 2011. “Nos passos dos clássicos: ecos do bucolismo antigo na primeira lira de Marília de Dirceu.” Caligrama: Revista de Estudos Românicos 12:215-235.

Public Scholarship and a Global Antiquity

A new open access study in Scientific Reports focuses on the prehispanic cocoa trade (led by Claire Lanaud and Hélène Vignes) by examining theobroma cacao residue from 352 vessels sourced from Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, Mexico, Belize, and Panama dating to from about 3,900 BCE to 1600 CE. They found that “the widespread use of cacao in South America out of its native Amazonian area of origin, extending back 5000 years, likely supported by cultural interactions between the Amazon and the Pacific coast.” People on the Pacific coastline travelled and traded in the substance extensively, to a much higher degree than previously known. Ergo, going long distances just for chocolate has always been a worthwhile, valid, delicious odyssey.

In Egyptology news, Yasmine Guy discusses “New Kingdom Egyptian Funerary Cones” for Black Perspectives; Mohamed Ismail Khaled is appointed the new Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (following on the heels of predecessor Mostafa Waziry facing criticism for his Menkaure Pyramid scheme); and people are getting stoked for the opening of the Great Egyptian Museum.

At her newsletter, The Colour of Time with Marina Amaral, professional historical photo colorist Marina Amaral talks about the very real danger presented by AI creating historical images. But, as Christina Riggs has noted and written on, Amaral’s own work to colorize photos can add to this confusion.

At the Peopling the Past pod, august classicist Shelley Haley joins the gang to discuss Cleopatra. As they say: “come for the Plutarch, stay for the Beyonce.”

What is the impact of the abysmal job market and increasing attrition in the field of history? In Foreign Policy, ancient military historian Bret Devereaux argues that “The History Crisis Is a National Security Problem.”

“This policy-created collapse of the history discipline has direct impacts on national security. The Department of Defense is one of the largest employers of academic historians in the United States, in positions ranging from office training as part of the service academies or Professional Military Education to unit-level command historians responsible for chronicling and analyzing the operations of their units and fielding requests for historical data.”

New historical fiction alert! In the Princeton alumni magazine, they speak to Oyin Sangoyomi (’23) about her new book, Masquerade, inspired by a mix of Nigerian mythology and the Greek myth of Persephone. As they note, “the novel is set in a reimagined 15th century West Africa based off the Oyo Empire (one of the most prominent in Yoruba history). It follows the journey of a young woman named Òdòdó, a blacksmith and outcast who rises to power after being kidnapped by the King and forced into marriage.” Sangoyomi was primarily taught post-colonial African history in school before undertaking her own research on medieval West Africa and taking a course on African Women Writers. Also note that the Afterlives of Ancient Egypt pod with Kara Cooney interviewed Malayna Evans, author of Neferura, about “the inspiration behind the story [of the princess and high priestess of Kemet], her writing process, and how her knowledge of Egyptology factored into the choices she made as she was writing the book.”

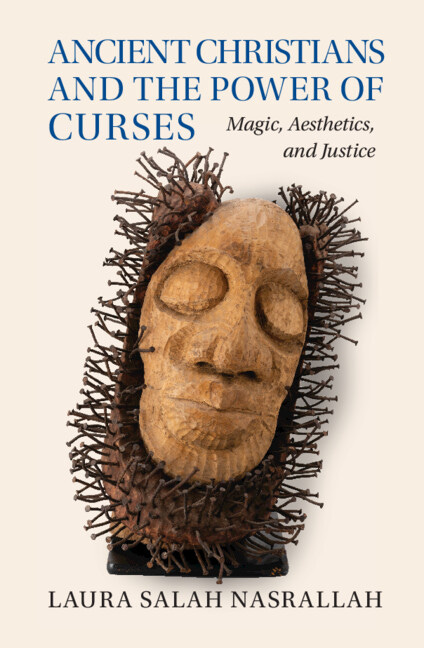

Over at the Yale Divinity School’s Reflections journal, they speak to Laura Nasrallah, the Buckingham Professor of New Testament Criticism and Interpretation at Yale, about everything from her childhood in Lebanon to the ways in which the past is represented today. Mentorship and treating her students as future colleagues are a big part of her pedagogy. As she remarks, “I believe I’m not there to give them knowledge but to co-produce it with them.” Her latest book, Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses: Magic, Aesthetics, and Justice, will be released this month by Cambridge University Press.

Mentoring is a critical but often under-appreciated part of academic life and success—and the Women’s Classical Caucus (WCC) wants to change this with its new mentorship award in honor of superb mentor Sharon James that celebrates and brings to light the often hidden labor of mentors:“The WCC has launched a new advocacy award to celebrate mentors and mentorship in the field of Classics. This award will be presented to an individual for their embodiment of the WCC ideal of "radical mentoring," as practiced by Sharon L. James, in their mentorship and deep support of others in the field of Classics. Click here to read more about the WCC Sharon L. James Mentorship Award.” The deadline for nominations is July 1, 2024.

And lastly, your editors have a new opinion piece out in Hyperallergic: “Discovery of 8,600-Year-Old Bread Gives Rise to Half-Baked Claims”. It is on the claim by archaeologists at Çatalhöyük that they have recently unearthed the oldest bread in the world (despite older evidence to the contrary from Jordan). We really, really wish we could take credit for that title but alas, it was our masterful editor Valentina Di Liscia who won the pun war.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

New #openaccess journal Res Difficiles Vol. 1, No.1 (2024)

Akroterion Vol. 68 (2023) #openaccess

Revue de l'histoire des religions Vol. 241, No.1 (2024)

Journal of Data Mining & Digital Humanities Special Issue (2024) #openaccess Historical Documents and Automatic Text Recognition

Renaissance Studies Vol. 38, No. 2 (2024) NB Yaliang Fu “Matteo Ricci's Depictions of Alexander the Great in Late Ming China”

Vox Patrum Vol. 89 (2024) #openaccess

After Constantine No. 4 #openaccess (2024)

Indo-Iranian Journal Vol. 67, No. 2 (2024)

Novum Testamentum Vol. 66, No. 2 (2024)

Hesperia Vol. 93, No.1 (2024)

Semitica et Classica Vol. 16 (2023)

Journal of Latin Cosmopolitanism and European Literatures No. 9 (2024) #openaccess Latin-Greek Code-Switching in Early Modernity

Anzeiger für die Altertumswissenschaft Vol. 76, No. 4 (2023) #openaccess

Religion in the Roman Empire (RRE) Vol. 9, No. 3 (2023) #openaccess Urban Representations of Religion

American Journal of Philology Vol. 144, No. 3 (2023)

Cahiers « Mondes anciens » Vol. 18 (2024) #openaccess (Se) réunir dans l’Antiquité

American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 128, No. 2 (2024)

Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology Vol. 10, No. 4 #openaccess(2024)

Journal of the History of Collections Vol. 36, No.1 (2024)

Codex - Revista de Estudos Clássicos Vol. 11 no. 2 (2023) #openaccess Dossiê A emoção no drama antigo: comédia e diálogo platônico

The Classical Review Vol. 74, No.1 (2024) NB Elton Barker, et al. “Digital Approaches to Investigating Space and Place in Classical Studies”

Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies Vol. 48, No.1 (2024) Seeing through Byzantium: Essays in Honour of Leslie Brubaker

Acta ad archaeologiam et artium historiam pertinentia Vol. 34 No. 20 N.S. (2022) #openaccess City, Hinterland and Environment: Urban Resilience during the First Millennium Transition

Greece & Rome Vol. 71, No.1 (2024)

Global Antiquity CFPs, Lectures, Workshops, and Events

The Future of the Past Lab, within the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Religions and Cultures (CNRC) at the University of Minnesota, would like to announce the a call for fellows on: Exploring the Assumptions of Cultural History.

On Thursday, March 21, 2024 at 5pm ET, at Duke’s Elizabeth A. Clark Center for Late Ancient Studies, Susanna Elm will join them to discuss “Forever Young and Beautiful: Masculinity and Imperial Representation in the Early Theodosian Age.” Please register here. This event will take place in the Breedlove Conference Room (Rubenstein 349) and will be available online for those unable to attend in person.

There will be a Tribute to Jan Assmann on Wednesday, April 3, 2024 at 3.30PM (Heidelberg) / 4.30PM (Cairo). The online stream is via zoom

dainst-org.zoom.us/j/92072929375.