Pasts Imperfect (3.20.25)

Ancient Thrace, Scented Statues, the Real Mexica, Cuneiform Spreadsheets, the (Digital) Geography of Pliny, Domestic Cats during the Tang Dynasty & Much More

This week, Sara E. Cole, Associate Curator of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum (Getty Villa) in Los Angeles, discusses the recent exhibition, Ancient Thrace and the Classical World: Treasures from Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece, and the current state of the Getty Villa following the devastating California fires. Then, the rise of domestic cats in Tang China, the real history of the Mexica, an interactive map of Pliny’s Natural History, the SCS celebrates outreach and reaffirms their commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion, observing Nowruz, Cuneiform spreadsheets, Black Africans and the Italian Renaissance, addressing the upheaval at Columbia, new ancient world journals, and much more.

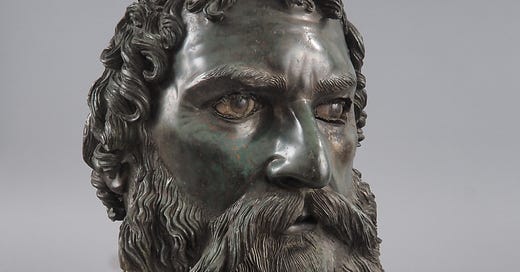

Ancient Thrace at the Getty Villa Museum by Sara E. Cole

On November 4, 2024 a major international loan exhibition opened at the Getty Villa Museum in Pacific Palisades, CA called Ancient Thrace and the Classical World: Treasures from Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece.

The exhibition was about six years in the making and involved a partnership between the Getty, the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Bulgaria, and the National Archaeological Institute with Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in Sofia. With over 200 objects on loan from fourteen Bulgarian museums as well as from Romania, Greece, and other institutions in Europe and the US, the exhibition probed the fascinating culture of the ancient Thracians. These peoples (who we should probably think of in a plural sense and not as a single cultural group) inhabited what is today Bulgaria and parts of Romania, Greece, and Turkey.

Thrace remains in many ways under-appreciated in the scope of ancient Mediterranean history, and the exhibition sought to bring it more fully into the mainstream. One reason for this is that the Thracians left behind very little in terms of written records. They did have their own language (or languages), which was Indo-European, and they adopted the Greek alphabet to write it, but only a handful of inscriptions survive. Much of what we know (or think we know) about the Thracians comes down to us through the often biased accounts of Greek authors like Herodotus and Thucydides. They characterize the Thracians as a tribal people known for their rich metal resources, skilled horsemanship, and prowess as warriors. The most famous historical Thracian in pop culture is undeniably the gladiator Spartacus, whose story as leader of a slave rebellion in Rome in the first century BCE is told in Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1960 film (watch Monica Cyrino’s lecture on it below).

But there isn’t much that we concretely know about Thrace – we have stories told by Greek and Roman sources that are surely embellished or modified to serve particular ideological ends, and we have modern-day films, operas, and stage musicals fictionalizing ancient Thracian lives both historical (Spartacus) and mythical (Orpheus). One of the exhibition’s driving themes was that by approaching Thrace through the region’s rich archaeological record we can seek to better understand Thrace on its own terms, refocusing Thrace as a center rather than a periphery. Artifacts found in Thracian lands reflect the intersection of multiple cultural influences. Through these objects, we can begin to parse the Thracians’ networks of relationships with their neighbors, including Greece, the North Aegean, the Black Sea, Anatolia, Persia, Rome, and Central Europe.

The exhibition was part of an ongoing initiative at the Getty that we call The Classical World in Context, a series of exhibitions, publications, and related programming that explore the diverse cultures that interacted with ancient Greece and Rome. As Greek and Roman art form the core of the Getty Villa’s permanent collection, these endeavors allow us to present our visitors with a fuller and more nuanced narrative about the diversity and interconnectivity of the world in which Greece and Rome were situated. Previous exhibitions focused on Egypt (2018) and Persia (2022). A future exhibition is being planned on Anatolia.

Ancient Thrace and the Classical World was scheduled to run through March 3, 2025 but the tragic outbreak of the Palisades Fire on January 7, 2025 forced its early closure. The Villa remains closed until further notice. The museum and its collections were unharmed by the fire, in part thanks to rigorous emergency preparedness measures and in part thanks to the heroic efforts of staff who remained on site to protect the property.

During its two-month run, the exhibition was seen by about 55,000 visitors. The Getty and its partners did explore the possibility of extending the show, but determined it was unfeasible given the current circumstances. Curators are, however, making efforts to continue sharing the exhibition with online audiences, and there are several ways you can still engage.

In terms of public outreach, classicist Matthew Sears kicked off a series of programs with an illuminating online lecture asking “Who Were the Thracians?,” which you can now view on YouTube:

A digital exhibit on Getty’s Google Arts & Culture page dives into the intricate and sometimes inscrutable imagery of the nine solid gold vessels that form the Panagyurishte Treasure, the most famous Thracian treasure hoard.

Our initial plan for the exhibition’s final week was to host a large in-person public program, featuring talks by archaeologists working in Thracian territory in Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece. Although it was not possible to hold the event at the Villa as intended, we are transitioning to an online program on April 28, 2025. You can register here.

And finally, in the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue produced by Getty Publications, you can read up-to-date scholarship on ancient Thrace and see wonderful photographs and discussions of each artifact.

Although the exhibition’s run was truncated, I and my colleagues hope that the resources this project has generated will prompt us all to rethink Thrace and reframe an outdated perspective that sees the region as a borderland or periphery of the Greek world to instead recognize it as one important actor among many in a complex Mediterranean network.

Global Antiquity and Public Humanities

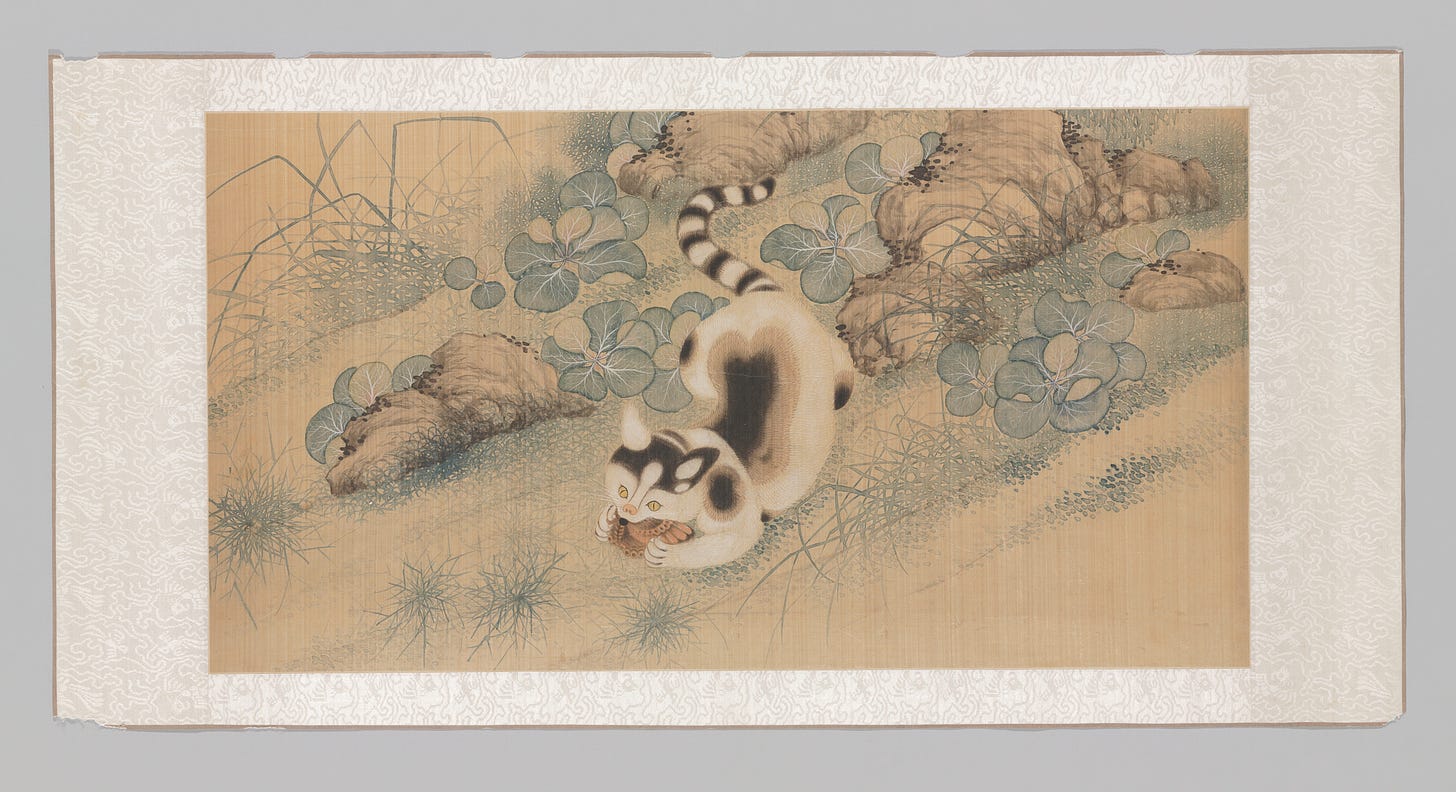

Over at LiveScience, science writer Sascha Pare discusses how aDNA analysis has led to better understanding of how domestic cats arrived in China around 1400 years ago. The article looks at a preprint authored by a number of leading paleogeneticists and bioarchaeologists, such as Yu Han, Songmei Hu, Ke Liu, and many others—but has not yet passed peer review. It is currently titled “Leopard Cats Occupied Human Settlements in China for 3,500 years before the Arrival of Domestic cats in 600-900 CE around the Tang Dynasty.” The researchers argue that:

Following several centuries’ gap of archeological feline remains, the first known domestic cat (706–883 CE) in China was identified in Shaanxi during the Tang Dynasty. Genomic analysis suggested a white or partially white coat and a link to a contemporaneous domestic cat from Kazakhstan, indicating a likely dispersal route via the Silk Road.

Over at the podcast “Gone Medieval,” host Matt Lewis speaks to Camilla Townsend to “delve into the story of the Mexica, commonly known as the Aztecs. They unpack the true history behind the label 'Aztecs’”—and dispel the many myths that surround them. Also, just a side note that there is an upcoming exhibition at the San Antonio Museum of Art, “Maya Blue: Ancient Color, New Visions,” which looks fantastic.

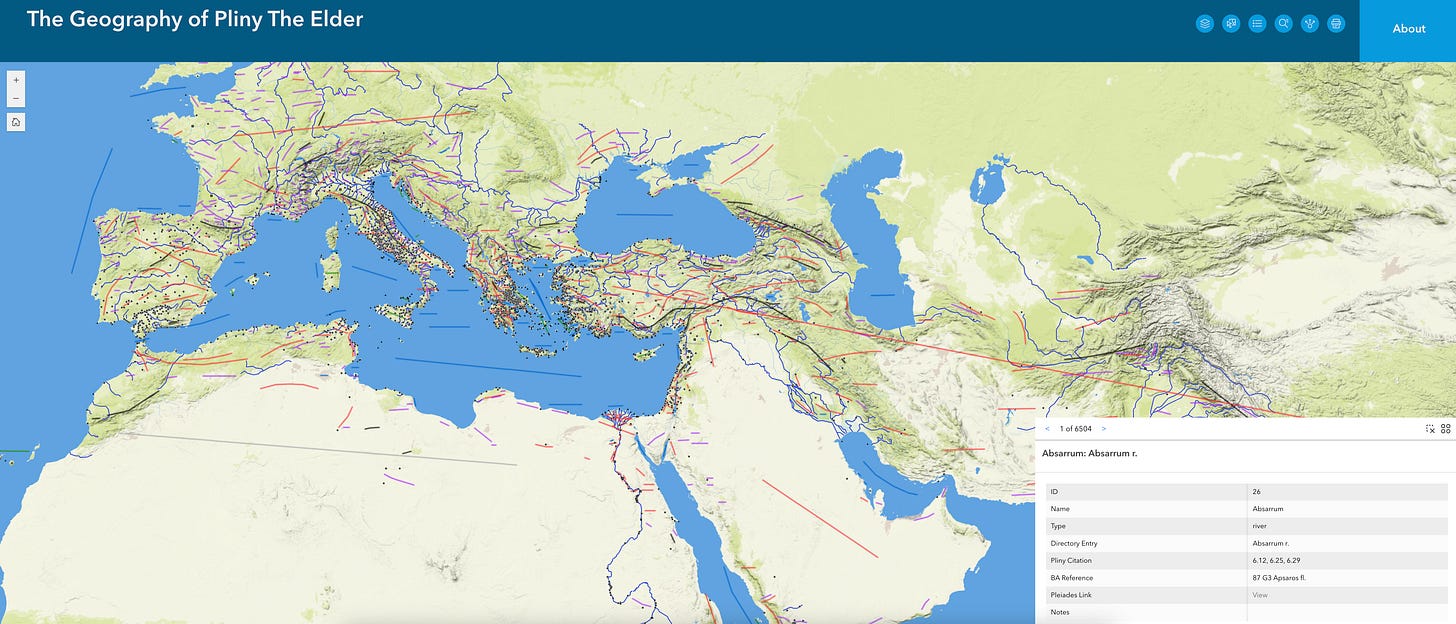

The Ancient World Mapping Center (AWMC) has announced the launch of their digital maps of The Geography of Pliny the Elder. As they note, the project “compiles and maps the geographic data in Pliny's Natural History. The database, available for download from the ISAW website, includes some 6,500 unique entries, and this application maps all those entries that are locatable. Users can click on a feature or use the search function to find citations in Pliny and a link to a feature's associated Pleiades entry, where further data, much of it beyond the scope of Pliny, can be found.” The application was developed by Grace Bell, Gabe Moss, Brian Turner, Richard J. A. Talbert, and the staff of the Ancient World Mapping Center.

In archaeology news, a mikveh (Jewish ritual bath) was found at Ostia; two iron ankle shackles were discovered at the Ghozza mine in Egypt, a find that points to the brutal toll of gold mining under Ptolemy I; and archaeologists are now arguing for re-dating of the Iron Age in ancient India. But before we celebrate too heartily, let us not forget that the Guardian has now reported that “Palestinian experts working with British archaeologists estimate that more than two-thirds of heritage, cultural and archaeological sites in Gaza, have been damaged, often very badly.” All cultural heritage is worth protecting.

Over at the Society for Classical Studies (SCS), the Outreach Prizes Committee announced that Candida R. Moss was awarded the 2024 Mary-Kay Gamel Outreach Prize. As they note, she is a “public intellectual who has written as a columnist for The Daily Beast and is most recently the author of God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible.” The committee also awarded Max Miller of Tasting History the 2024 Forum Prize. As they note, “Tasting History is a vibrant, engaging public resource on living history available to a mass audience. Max Miller’s artful synthesis of research, humor, and authentic engagement with ancient recipes has created and sustained a huge YouTube audience, both academic and popular.” We admit that we are one of the millions who have watched his garum video. Congrats to these two stellar examples of outreach and engagement!

But on a more serious note, the SCS Board of Directors also reaffirmed its mission statement in the midst of Trump’s attacks on DEI in higher education: “We here reaffirm that one of the goals of the SCS is to make the study of the ancient Mediterranean past accessible, available, and attractive to all communities, especially those that have not traditionally engaged in the study of Classics.” Read the whole statement here.

It’s well established that Greco-Roman statues were often polychrome; new research by Cecilie Brøns (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen) suggests that many of them also smelled delightful. Her paper “Scent of Ancient Greco-Roman Sculpture” just published in Oxford Journal of Archaeology brings together the substantial literary, epigraphic, and artistic evidence that statues of gods were regularly perfumed. Encounters with Greco-Roman religious sculpture were olfactory as well as visual.

At the Berliner Antike Blog, Anuj Misra, director of the new Max Planck Research Group, Astral Sciences in Trans-Regional Asia (ASTRA), and professor at the Freie Universität Berlin, answers ten questions about his career, research, and the “inherent interconnectedness of the technical, socio-historical, and cross-cultural aspects of astral sciences.”

The events at Columbia University over the past few weeks have been, frankly, horrendous. Classics professor and activist Joe Howley has been on the frontlines fighting for the return of his friend, Columbia grad student and lawful permanent resident Mahmoud Khalil. Howley wrote a great piece for Lit Hub, “A Columbia University Professor Speaks Out Against the Kidnapping of Mahmoud Khalil.”

Early this morning, the Persian New Year, known as Nowruz (نوروز), began. The Spring Equinox ushers in this “new day” for millions, so maybe try some mahi ba zafferan (saffron fish) or nan-e-keshmeshi (raisin cookies) today in celebration. In addition, we wanted to commend historian Touraj Daryaee on becoming the new editor of the Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Were spreadsheets more or less of a drag when they were inscribed stone tablets? Archaeologists at the Girsu Project, a collaboration between the British Museum and the Iraqi government’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, unearthed hundreds of tablets in modern-day Tello. As the Guardian notes:

One tablet lists different commodities: “250 grams of gold / 500 grams of silver/ … fattened cows… / 30 litres of beer.”

Tag yourself. I’m fattened cows.

Researchers at the Myaamia Center at Miami University of Ohio are working hard to save the Miami language through linguistic research. While a few native speakers still remain, tribal members and linguists are collaborating on a project sponsored by the Mellon Foundation, called the National Breath of Life, to revitalize Indigenous language learning.

If you didn’t have a U-Haul—or wheels, for that matter—how would you move cross-country? Experimental archaeology at White Sands National Park in New Mexico has yielded some answers to the question “what the heck are these fossilized grooves and footprints doing here?”

Researchers think the grooves are the remnants of tracks left behind by “travois,” an ancient transport vehicle used before the invention of the wheel. The travois appear to have been made of poles that were either joined together at one end or crossed in the middle. Their users would have loaded them up with bulky objects, then grabbed the poles and dragged them behind them — similar to using a wheelbarrow or rickshaw with no wheels.

While dogs or horses could drag a travois, the White Sands researchers believe that humans were the main source of power for these wooden tools. I dunno, could be useful for your next trip to Costco?

Following a screening of the documentary "The Black Italian Renaissance: African Presence in Art" at NYU in NYC last week, a brilliant panel of artists and art historians—Angelica Pesarini, Ann Morning, Deborah Willis, and Justin Randolph Thompson—convened with Isabella Livorni as moderator. What they addressed was the fundamental roles of Africans in the Italian Renaissance: “Blackness is not always immediately associated with Italian Renaissance history, but African people and people of African descent were integral parts of the Italian Renaissance.” You can watch the panel discussion here.

Just published #openaccess: Ancient Pasts for Modern Audiences: Public Scholarship and the Mediterranean World, edited by Chelsea A.M. Gardner & Sabrina C. Higgins, brings together fifteen contributions from scholars bringing research on the ancient Mediterranean, North Africa, and Western Asia to a broader audience.

Finally, we all need a little bit of nerd humor right now and this made me lol.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 129, No. 2 (2025)

Bulletin de correspondance hellénique Vol. 146, No. 1, No. 2 (2022) #openaccess

Buried History: The Journal of the Australian Institute of Archaeology Vol. 60 (2024) #openaccess

CLARA Vol. 12 (2024) #openaccess The Arvid Andrén Collection at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo

eisodos Sonderausgabe No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Greece & Rome Vol. 72, No. 1 (2025)

Journal of Roman Archaeology Vol. 37, No. 2 (2024)

Mnemosyne Vol. 78, No. 2 (2025)

Early Science and Medicine Vol. 30, No. 1 (2025)

Méthexis Vol. 37, No. 1 (2025)

Phronesis Vol. 70, No. 2 (2025)

The Review of Metaphysics Vol. 78, No. 3 (2025)

Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus Vol. 23, No.1 (2025)

Novum Testamentum Vol. 67, No. 2 (2025)

Vox Patrum Vol. 93 (2025) #openaccess

Journal of Late Antique, Islamic and Byzantine Studies Vol. 4, No 1 (2025)

Journal of Late Antiquity Vol. 18, No.1 (2025) #openaccess Translation and Greek-Latin Bilingualism in Late Antiquity

Anales de Historia Antigua, Medieval y Moderna Vol. 58 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess Materialidad e institución en la Edad Media: la complicidad entre sujeto y objeto

Mirator Vol. 24, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess Preservation – Renewal – Change

Renaissance Studies Vol. 39, No. 2 (2025)

Arheologia = Археологія No.1 (2025)

Dead Sea Discoveries Vol. 32, No. 1 (2025)

Libyan Studies Vol. 55 (2024)

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society Vol. 90 (2024)

JAOS: The Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 145 No. 1 (2025)

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient Vol. 68, Nos. 1-2 (2025)

The Journal of Religion Vol. 105, No. 1 (2025)

Revue de l'histoire des religions Vol. 242, No. 1 (2025)

Events, Workshops, and Exhibitions

The Res Difficles 6 conference occurs online tomorrow, Friday, March 21st, starting at 9:20am PST. It features a keynote by Sarah Debrew “Africa in the Classics Curriculum.” Registration is required.

On Monday, March 24th at 15:00–16:00 GMT, Chijioke Okorie (University of Pretoria), will visit the Material Digital Humanities seminar to discuss “Digital treatment of African cultural heritage: Shifting landmarks and implications for copyright exceptions for archives.” As they note, “[Okorie] examines how copyright law must adapt to facilitate digital treatment of African cultural heritage. It challenges traditional notions of preservation and access, advocating for "agency" as a vital guiding principle for digital treatment. The talk further highlights how this shift empowers institutions and prepares them for future copyright reforms, fostering decolonization and restitution in archival practices.” Online only and free, but booking is required here.

On Wednesday, March 26th at 5:00 pm (GMT) Eleftheria Katsoni (UCL) will discuss: “The Study of a Third-Century Erotic Agōgē Spell: A New Papyrus from Oxyrhynchus.” The UCL Lyceum notes, “This paper presents an unpublished third-century papyrus from Oxyrhynchus, which preserves a nearly intact example of an erotic spell…The study utilises a combination of traditional philological methods and digital tools to analyse the text.” To attend either in person or online, please register using this link.