Pasts Imperfect (2.6.25)

The ‘Genetics Turn’ in Disease History, Avar Migration, Greek Fish Addictions & More

This week, medievalist and historian of medicine Monica H. Green discusses the “Genetics Turn” in the field of infectious disease history and how it is restructuring the history of the past. Then, using ancient DNA (aDNA) to track Avar migration in late antiquity, a new book on ancient Roman strikes, the saga of the Sappho papyri continues, the medieval origins of Lunar New Year, a new exhibition focused on Zakariyya al-Qazwini’s medieval cosmography, transcribing primary documents on Douglass Day, new ancient world journals, and much more.

The ‘Genetics Turn’ in Disease History: What It Means to ‘Retrospectively Diagnose’ in an Age of Evolutionary Pathogen Histories by Monica H. Green

[This is an abbreviated summary of arguments presented at the session “Medical Modernities” organized by the Society for Ancient Medicine and Pharmacology at the Society for Classical Studies 2025 meeting in Philadelphia. A complete bibliography of the works cited in the talk can be found online.]

__

“Bubonic Plague Discovered in Ancient Egyptian Mummy DNA.” “Were the Vikings History's Original Superspreaders?” What should we make of such breathless headlines?

New disciplines and methods, especially in the field of infectious disease history, are restructuring the history of the past. And not a moment too soon! The experiences of the last several years underscored how little we have known about past pandemics, and how important it is that we know more.

Epidemics and pandemics are hardly undiscussed in the scholarship of the classical world. Just look up “cause of the Plague of Athens (430 BCE)” or the Antonine Plague (165-180 CE). But a lot of that discussion has been ill-informed. Attempts by academics to try and identify a disease or pathogen from the past, often termed “retrospective diagnosis,” elicits more opprobrium in the field of medical history than respect.

Why the disdain for historical diagnoses? Until recently, there has been an evidentiary barrier between scholars of the past 150 years and every prior stage of history. Whereas modern medical diagnoses are based on lab tests, x-rays, and myriad technologies to assess the identities of microorganisms, without those technologies the historian can usually know nothing beyond the words used to describe diseased bodies. However, the field of medical history has a sister discipline, paleopathology, that can aid historians by assessing certain disease histories from physical remains. For slowly debilitating diseases like tuberculosis or leprosy, it is possible to use paleopathological methods to identify advanced infections on the basis of systematic lesions in the bones, for instance. However, for those conditions that killed quickly, like plague, there was no hope of establishing their historical presence—until recently.

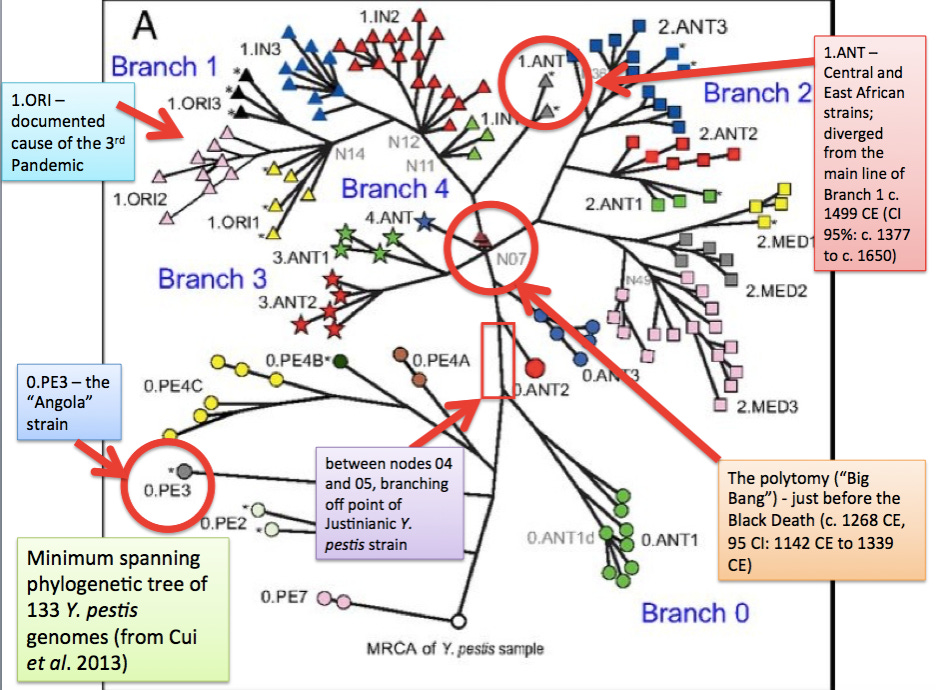

Enter genetics, or more specifically, evolutionary paleogenetics. By retrieving “molecular fossils” from bone, teeth, or mummified tissues, it is possible to retrieve and reassemble the genomes of bacteria and even viruses. Where there is good preservation, it has been possible to identify leprosy (Mycobacterium leprae) in 3rd century BCE remains from Egypt. Researchers also identified probable tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex) at the Casa del Fabbro in Pompeii. And there has been the significant discovery of plague (Yersinia pestis) at various sites around the Mediterranean and in Europe. And since those “palaeogenomes” can be compared to surviving strains, the pathogen’s evolution—and thus, its history—can be revealed in phylogenetic trees.

A 2013 diagram showing the evolution of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague, marked here for the lineages relevant for African history. Source: Green 2018, fig. 1, based on Cui et al. 2013, fig. 1A.

There are some drawbacks to the process. Paleogenetics is expensive, the samples retrieved are few, and they don’t necessarily tell us about the times and places of most importance to human history. That leaves us in a limbo between the evidence available and the major questions we still have.

What do we do in the interim? What we do is think through the gaps creatively.

We can look to smallpox for an example. It has been known for several decades that the variola virus, which causes smallpox—declared eradicated by the Global Health Assembly as a global disease in 1980—was closely related to pox strains found in camels and African gerbils. But how long variola has been smallpox and not some more generic disease (presumably with different symptoms and epidemiological patterns) was unclear.

And when did smallpox become the disease we knew in the twentieth century? A study published in 2016 retrieved variola from a 17th-century European mummy, and claimed that what we knew as modern variola had likely only existed since the 16th century. This was stunning, since smallpox had long been associated with the Antonine Plague in the 2nd century CE and even further back, allegedly causing the facial scars on the mummy of Ramesses V (r. 1147-1143 BCE). Was smallpox not as old as commonly believed? If so, what were we to make of references to variola by the 6th-century bishop, Gregory of Tours, or other written descriptions?

Flash forward to 2020. Another genetics team announces that they have retrieved variola virus from several sites in northern Europe, 7th to 11th centuries. These new strains (“Viking” lineages) are basal to (that is to say evolutionarily older than) modern smallpox; however, theyare not its direct ancestors. They share some but not all of modern variola’s distinctive genes. In any case, the “Viking” smallpox genomes retrieved thus far aren’t early enough to associate with the Antonine Plague, leaving that part of the pathogen’s history unresolved..

That brings us to 2024. A new bioarchaeological study authored by Haoyue Zhao and Andrew Wilson identified an individual from 3rd- or 4th-century Cirencester—about a century before the Roman occupation of Britain ended. No testing was done for variola aDNA, but skeletal analysis showed signs of osteomyelitis variolosa, a condition of the joints and long bones characteristic of a smallpox infection acquired in childhood, when the bones are still forming.

Were these lesions caused by an ancestor of the “Viking” variola? Or of the modern one (whose common ancestor with the “Viking” lineages must have existed by Roman times)? Right now, we can’t be sure. But these paleopathological and genetic findings can be juxtaposed with clinical descriptions written in 10th century Islamic medical texts and 11th-century poetry. Each of these sources uses the same Arabic word, judarī, and connects the disease with permanent facial scarring and severe pain in the limbs.

Is this all the same pathogen in the Roman, Viking, Abbasid, and early modern European periods? Clearly not, since the variola virus was evolving throughout this time, sometimes disappearing into evolutionary dead ends. But just as we would now categorize Omicron and the many other strains of SARS-CoV-2 as all part of the COVID pandemic, coherent narratives about variola/smallpox in the ancient and medieval pasts seem to be similarly coming into view.

We can take a number of approaches when considering this state of incompletely overlapping evidence. We can address it with dismissive skepticism (“This proves nothing!”), or we can hone a patient awareness that we are just at the beginning of figuring out how genetics, bioarchaeology, and history can work together to reconstruct the histories of infectious diseases. Yes, some knowledge of evolution helps, as does reference to basic concepts of pathogen genesis (spillovers, zoonotics, animal reservoirs). But collaboration is key: Pooling many minds and disciplinary perspectives also allows thinking at continental, hemispheric, and even global scales.

Rather than taking the claims of individual headlines as decisive, we should perhaps treat new work as discursive and provisional. In this manner, we can encourage new lines of investigation to develop. We can also actively engage in this ongoing dialogue by attending conference sessions. Keep an eye out for pre-prints. The scope and extent of the Justinianic Plague, for instance, will be expanded this year with a session on the Middle Danube region at the International Medieval Congress at Leeds; a forthcoming volume of essays on plague in Asia will pick up a line of analysis that’s been hanging since the 1970s. Consensus will form on certain issues as confirmatory studies accumulate.

On other issues, controversy will continue, not because of the skepticism of cranks, but because debate about methods and interpretations is the sign of a healthy discipline. Getting scientific and humanistic approaches to disease history into alignment will take patience and good faith, but the results may well be not simply headline-grabbing but profoundly transformative of our ability to understand the ancient world.

--

Recommended Readings

Chouin, Gérard. “Environments of Health and Disease in Tropical Africa before the Colonial Era,” in: Disease and the Environment in the Medieval and Early Modern Worlds, ed. Lori Jones (London: Routledge, 2022), 127-158.

Duchêne, Sebastián, Simon Y. W. Ho, Ann G. Carmichael, Edward C. Holmes, and Hendrik Poinar. “The Recovery, Interpretation and Use of Ancient Pathogen Genomes,” Current Biology 30 (5 October 2020), R1215–R1231.

Green, Monica H. “The Pandemic Arc: Expanded Narratives in the History of Global Health,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Science 79, no. 4 (October 2024), 345–362.

Simons, Julia G. “Tuberculosis in the Greco-Roman World,” PhD dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2023.

Global Antiquity and Public Humanities

Did someone say collegia? Or we love and support collective action? Pasts Imperfect co-editor and co-founder Sarah E. Bond’s new book with Yale Press, Strike: Labor, Unions, and Resistance in the Roman Empire, came out on Tuesday. Dr. Bond spoke about it on Anthony Kaldellis’ podcast, Byzantium & Friends, but you can also listen to her discuss it at ISAW-NYU in March, if you like.

In Nature, there is a new article on the long-distance migration of the Avars. In “Ancient DNA reveals reproductive barrier despite shared Avar-period culture,” the lead authors examine the Eastern Asian ancestry and ancient genome-wide data of 722 Avars buried in two cemeteries south of Vienna, Austria. The Avars arrived in Eastern Central Europe around 567-8 CE, but the researchers underscore there was a “reproductive barrier” maintained between neighboring Avar populations.

Big congrats to PI friend and newly minted PhD, Dr. Jermaine Bryant! He has now been named to the Society of Fellows of Harvard University. Dr. Bryant recently defended his dissertation, “Roman Post-Triumviral Elegy and the Rhetoric of Trauma.” Read more at the Princeton Classics blog.

Shout out to Serena Witzke for starting a newsletter, “Ancient Rome, Modern Witch,” with a witchy look at Circe. And at Donna Zuckerberg’s newsletter, she has a great post on “ancient Greek things I've seen on TV that haunt me.” She finally calls out the notorious “Atlatis” cookie from Great British Bake Off, which she rightly notes “wasn’t Kim-Joy’s fault, but rather Sandy’s.” If somebody says “it’s all GRΣΣΚ to me” one more time, I will scream. Clearly a case of Accursius’ ‘Graecum est—non legitur!’

Over at Oxford, papyrologist and cultural heritage expert Roberta Mazza spoke about “The Unsettling Story of the Brothers Poem Papyrus.” The lecture was recorded (see below), but Dr. Mazza addresses the controversy in her book, Stolen Fragments: Black Markets, Bad Faith, and the Illicit Trade in Ancient Artefacts. As she notes, the “discovery of a papyrus with new verses of Sappho, mentioning her brothers, made the headlines” in 2014. But there is a new twist to the story. Also note that the BBC has announced that Mazza will lead a new series looking at the papyri trade and the Museum of the Bible.

Haute couture, haute culture, fancy dresses and ancient objects side-by-side at the Louvre, what more could a girl want? In a new exhibit, “Louvre Couture,” curator Olivier Gabet has placed some of fashion’s greatest masterpieces next to artifacts from the museum’s department of decorative arts. It’s on until July 2025, if you find yourself lucky enough to be in Paris.

At UC-Irvine’s humanities blog, Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies Xiao Rao examines the medieval roots of Lunar New Year.

During the early Chinese empires, the Qin (221–206 BCE) and Han (202 BCE–220 CE), the consolidation of calendars and customs unified disparate local celebrations of seasonal agricultural activities into a nationwide system of annual festivals… [a later] interesting aspect of these beliefs and practices is the use of puns in the symbolic foods or items prepared for the festival. For instance, the modern custom of including fish (yu, 魚) in the New Year feast stems from the pun between “Every year brings fish” (nian nian you yu, 年年有魚) and “Every year brings surplus” (nian nian you yu, 年年有餘).

We are always fishing around for more holidays that include puns.

Oh man, I hate it when I accidentally throw something out that I didn’t mean to. Like, for instance, an ancient Greek statue. Some poor guy found this Hellenistic statue of a goddess in a plastic bag when he was taking out the trash in Thessaloniki. It could happen to anyone.

The latest installment of Princeton University Press’s “Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers” series is out: How to Eat: An Ancient Guide for Healthy Living. In it, ancient medicine expert Claire Bubb, Assistant Professor of Classical Literature and Science at ISAW, selects, translates, and comments on a range of ancient advice on healthy eating. And finally: here’s a palate cleanser for the past couple weeks of horrible headlines: Amelia Soth’s piece in JSTOR Daily about fish addiction in ancient Greece. Uh oh…it’s me!

An opsophagos was a kind of tyrant of the dinner table, brutal, self-absorbed, and unrestrained—with those qualities threatening to spill over into other aspects of life.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Anzeiger für die Altertumswissenschaft Vol. 77, No. 3 (2024) #openaccess

Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies Vol. 67, No. 1 (2024) 70th Anniversary Issue

Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum Vol. 147 (2024) #openaccess Scribes and Language Use in the Graeco-Roman World

Chronique d'Egypte Vol. 99, No. 197 (2024)

Dumbarton Oaks Papers Vol. 78 (2024) #openaccess NB Samet Budak “Teaching Greek, Studying Philosophy, and Discovering Ancient Knowledge at the Ottoman Court in the Fifteenth Century”

Les Frontières Vol. 10 (2024) #openaccess Les frontières du travail

FuturoClassico Vol. 10 (2024) #openaccess

Helios Vol. 51, No.1 (2024)

Journal of Latin Linguistics Vol. 23, Nos. 1-2 (2024)

Lexis Vol. 42, No.2 (2024) #openaccess NB Patrick J. Finglass “Greek Lyric Fragments in Margaret Goldsmith’s Sappho of Lesbos”

Lucentum Vol. 44 (2025) #openaccess

Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome Vol. 69 (2024) #openaccess Special Section: A Tribute to Malcolm Bell III, 1941–2024

Mnemosyne Vol. 78, No. 1 (2025)

Römisches Österreich Vol. 47 (2024) #openaccess

Vita Latina No. 205 (2025) #openaccess

Ancient Philosophy Vol. 45, No. 1 (2025) NB Emily Hulme “Cynic Egalitarianism, Cynic Misogyny?”

Aristotelica Vol. 6 (2024) #openaccess António de Castro Caeiro, “The Snubness Structure and the Inextrictable Soul-Body Relationship”

Ciceroniana On Line Vol. 8 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess Lecturae Ciceronis I, 2024. Le De inuentione entre philosophie, droit et rhétorique

Comparative Philosophy Vol 16, No. 1 (2025) NB Andrew Alwood, “Epicurus and the Buddha on Desire”

History of Philosophy & Logical Analysis Vol. 27, No. 2 (2024) NB “‘Wrangling Over the Shadow of an Ass’ – On Lucian’s Socratic Metaphilosophy”

Journal for the History of Astronomy Vol. 56, No.1 (2025)

Polis Vol. 42, No.1 (2025) New Directions in Roman Political Thought

Rhizomata Vol. 12, No. 2 (2024)

Analecta Bollandiana Vol. 142, No. 2 (2024)

Convivium Vol. 11, No. 2 (2024)

Early Medieval Europe Vol. 33, No. 1 (2025)

Interfaces: A Journal of Medieval European Literatures No. 12 (2024) #openaccess The Search for Books in Uncharted Territory, c. 800–1500; No. 11 (2024) #openaccess Occasional Literature and Patronage in Later Medieval and Early Modern Periods

Scrineum Rivista Vol. 21 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess Minitexts: A Window into Early Medieval Manuscript Cultures

Studia historica Brunensia Vol. 71 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess

Catholic Biblical Quarterly Vol. 87, No. 1 (2025)

Early Christianity Vol. 15, No. 1 (2024) NB Niels Bargfeldt, et al. “Materiality of Incarceration in Mediterranean Antiquity”

History of Religions Vol. 64, No. 2 (2024) NB Bruce Lincoln “‘Indo-European’ Cosmogony: Fifty Years Later”

Journal of Ancient Judaism Vol. 16, No. 1 (2025)

Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions Vol. 24, No. 2 (2024

Vetus Testamentum Vol. 75, No. 1 (2025)

Events, Lectures, and Workshops

Transcription adds to accessibility, and we need to provide reputable primary sources right now. So, join thousands online for “Douglass Day: A day of love & collective action for Black history! Douglass Day is an annual program that marks the birth of Frederick Douglass. Each year, we gather thousands of people to help create new & freely available resources for learning about Black history. We frequently focus on important Black women’s archives, such as Anna Julia Cooper (2020), Mary Church Terrell (2021), Mary Ann Shadd Cary (2023) and plenty more to come in future years.” You can register here.

Museum exhibition “Kyladitisses: Untold Stories of Women in the Cyclades,” is on view now in Athens until May 4, 2025 at the Museum of Cycladic Art. As they note, this exhibit “pays tribute to the women of the Cyclades, shedding light on their lives and their role in the societies of the islands of the Archipelago from the Neolithic period until the 19th century” with over 180 pieces on view.

For the Inaugural ICMA Associates Lecture 2025 on February 15, 2025 at 17:00 CET (11 am ET), Gerardo Boto Varela, will speak on “Royal Cemeteries in Medieval Iberia: Geopolitical System and Sites of Dynastic Memory.” Register here.

“Wonders of Creation: Art, Science, and Innovation in the Islamic World” opens at Boston College’s McMullen Museum of Art on Sunday (February 9th). The exhibit centers on Zakariyya al-Qazwini’s 13th-century cosmography, The Wonders of Creation and Rarities of Existence in a global context. On Monday, the 10th, at 6pm EST, the Museum’s Norma Jean Calderwood Lecture Series will feature a hybrid panel discussion “Exploring al-Qazwini’s Cosmology The Wonders of Creation and Rarities of Existence with Ladan Akbarnia, Emine Fetvacı, Travis Zadeh, and Margaret Graves.” See you online and in two weeks for the next edition of Pasts Imperfect!