Pasts Imperfect (12.5.24)

The Ancient Greek Underworld, Polychromatic Severans, Psychedelic Egyptian Breast Milk is Bes, Teaching Polybius & Much More

This week, Homer scholar Joel Christensen reviews a new book on the art and literature of the ancient Greek underworld, Life / Afterlife: Revolution and Reflection in the Ancient Greek Underworld from Homer to Lucian by Suzanne Lye. Then, psychedelic Egyptian breast milk, rejecting the siege mentality in Higher Education, a new translation of a medieval Arabic cookbook, a polychromatic reconstruction of Septimius Severus and Julia Domna to view before Gladiator II, a playlist to walk through the new Met exhibition with, teaching Polybius to young students, Beijing hosts the World Conference of Classics, new ancient world journals, and much more.

A New Guide to the Ancient Greek Underworld by Joel Christensen

Who’s afraid of a little eschatology? Probably not Classicists. Recent years have seen a series of fine studies on ancient Greece’s use (and abuse) of the underworld: from George Gazis and Anthony Hooper’s Aspects of death and the afterlife in Greek literature to Emma Gee’s Mapping the Afterlife: From Homer to Dante to a wave of publications on Orphic tablets and reception studies, the study of death remains quite alive.

Antiquity’s afterlife—the texts, fragments, and artefacts that remain—offers the persistent suggestion that death itself may be preferable to living.

Memento mori. Sure? But what does it mean to recall something surpassingly unknown and unknowable? I have always been more in the mindset of Plato’s Socrates in the Apology, who muses that death is either a dreamless sleep or an opportunity to join the countless spirits of the dead for some communion about the lives left behind them. While I suspect Plato set up that binary to force audiences to consider the impossibility and absurdity of the latter, the very concept is one that makes death a shadowy reflection of lives once lived, an extended metaphor of the heroic psukhe that leaves the body at the time of expiration and yet carries on, incorporeal, but still recognizable.

Suzanne Lye starts her riveting Life/Afterlife: Revolution and Reflection in the Underworld from Homer to Lucian with a different Platonic Socrates, the philosopher in his final moments in the Phaedo who reasons that for good and evil to matter to an immortal soul, then there must be an afterlife. This dialogic shift from an uncertain underworld to one that somehow acts as a guarantee of cosmic justice illustrates that the underworld is not merely a posterior reflection of how life was, but instead a notional space that helps us to explore what we think life should be. It can reward nobility in life, or it can be simply a continuation in one way or another. To crib from Modest Mouse, [if] “you wasted life, why wouldn’t you waste death?” (“Ocean Breathes Salty,” 2004).

Too often when we talk about underworld scenes from the perspective of myth and literature, we shoehorn it into the category of katabasis, that heroic journey to and return from the underworld that has been so popularized by modern ideas of the heroic pattern. Lye (full disclosure: I have known Suzanne since we met in graduate school over twenty years ago) sets out to explore the “ancient imaginary” for how authors use the underworld to “foment ideas that challenge the status quo and an audience’s perceptions of their lived reality” (1) and treats the Underworld as a “highly dynamic metaliterary space” where authors and audiences meet, comparing and exploring themes from different genres and periods.

Lye frames this material despite two considerable challenges. The first is that it is hard to disentangle representations of the afterlife as poetic themes and evidence for historical practice. How can we know what people believed or which believers engaged with texts that existed for different uses and for different audiences over time? Lye effectively neutralizes the first problem by treating depictions of the underworld as a constructed (and perhaps constructive?) narrative space.

This approach, nevertheless, takes us right to that second major problem: how to read and interpret across authors from different periods and moving between the cultural forests and those individual authorial trees. As someone who became a Homerist, I am always impressed by scholars who can move so deftly and expertly through time. Lye’s ability to trace metaliterary genre across authors and periods is a testament both to her own diligence and insight and also to the value of trying to do so.

I confess to being a happy member of the choir for such a literary sermon. Lye is clear and honest to the complexity of the interpretive issues, providing just enough to be understood, but not so little as to leave the reader feeling unmoored. Her overview of the functions of underworlds in Homer provides one of the clearest summaries of the nature and function of Homeric Nekuia and should probably be standard reading.

The book’s epilogue traces a few of these themes and questions from Greece to Vergil and Lucian. A longer book may have dwelled more in other philosophers or looked for additional confirmation from epigraphy where traditions of epitaphs will certainly support much of what Lye offers. But there’s no end to what might be said about a world we construct and contest. Understated but pressing on the pages of Lye’s book is the quite real effect that imagined afterlives continue to have on our ‘real’ lives today. I can’t think of the development of Underworld ideas without thinking about how they continue to be used to shape behavior in this before-life. We live in a time where world events have been shaped by those willing to give up their life to take others’; our politics are dominated by those certain about the nature and the wants of our eternal souls.

Mortal life, as Homeric epic would have us understand, derives its meaning from its limits. It has value because it cannot be replaced. The way we imagine existence after death can be fundamental in helping us appreciate this. And Suzanne Lye has provided us with an irreplaceable guide for thinking through how ancient authors and audiences did this, as well as a template for following her in a similar vein.

Global Antiquity and Public Humanities

In the New York Times, they cover the “Psychedelic Traces Found on [a] Mug From Ancient Egypt.” The Bes Mug is from the second century BCE and currently resides at the Tampa Museum of Art. The new study of the residue in it is published in Scientific Reports. Authored by Davide Tanasi, Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter, Fiorella Florian, and a number of co-authors, they find that “Egyptians may have used hallucinogenic substances as part of a fertility rite”. The researchers performed genetic analyses of chloroplast aDNA to confirm that Peganum harmala and Nymphaea caerulea plants “were deliberately used as sources of psychoactive substances for ritual purposes.” What is also surprising is the mixing of these substances in breast milk for ingestion.

In the LARB, Heather Hewett and Stacy M. Hartman address “Rejecting the Siege Mentality in Higher Education.” As Hewett and Hartman suggest, we might wish to hunker down and protect the current state of the humanities, but this mentality only serves the status quo. “After all, the phrase ‘the crisis in the humanities’ is over 100 years old,” they note. The two authors have been working with the American Council of Learned Societies and one of its programs, Building Blocks for a New Academy.

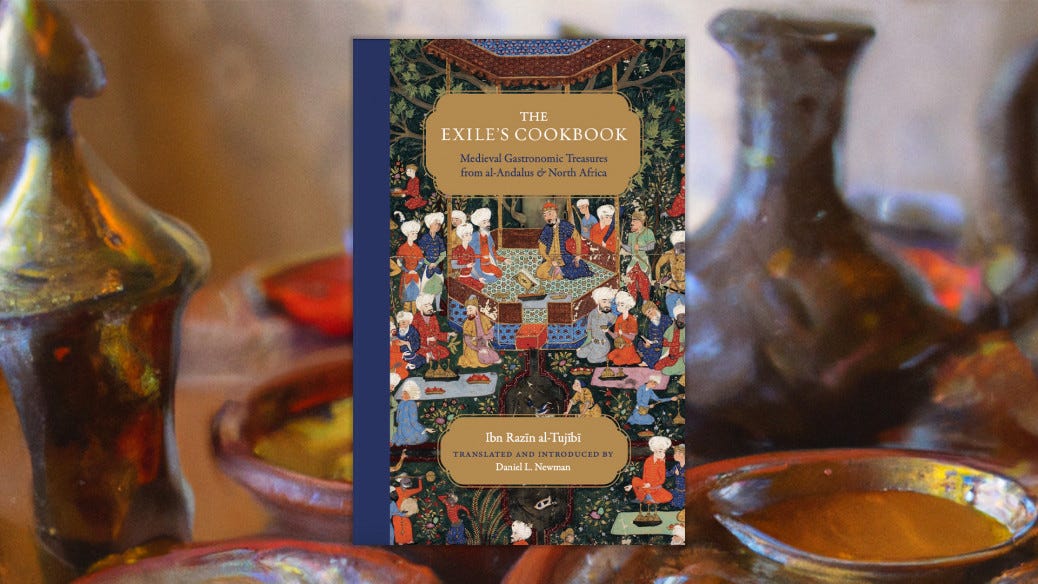

There is a new translation of Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī’s (1227-1293) thirteenth century Arabic al-Andalusi cookbook, Fiḍālat al-khiwān fī ṭayyibāt al-ṭaʿām wa-l-alwān, penned by professor and translator Daniel L. Newman. The Exile’s Cookbook: Medieval Gastronomic Treasures from al-Andalus and North Africa. There are 480 recipes, for everything from soups to hand-washing soaps. As Atlas Obscura notes, this is not Newman’s first time translating premodern cookbooks: “Newman’s first cookbook translation, The Sultan’s Feast, brought a 15th-century Egyptian text with over 300 recipes to an English-speaking audience.” But what grabbed my attention was the medieval Arab condiment, murri, “I found a 9th-century translation of a work by the Greek physician Galen, where the Arabic translator actually does translate the Greek garum—fermented fish sauce—as murri. But there’s a very clear distinction. What garum and murri both have in common is that they are the result of fermentation. We could even say that murri is like soy sauce, or like Thai fish sauce: In fact, with murri, the flavor is actually very close to soy sauce.” Hurray for fermentation!

Open access means accessibility. And the announcement that the edited volume Revelation and Material Religion in the Roman East: Essays in Honor of Steven J. Friesen is now OA? What a gift. I am also psyched to see that Edward William Kelting’s Egyptian Things: Translating Egypt to Early Imperial Rome is open access via UC Press.

The wildly popular YouTube education and art channel, After Skool, has a new animation focused on Polybius. In it, ancient historian Gregory Aldrete looks at the theories of Polybius and his ideas about why civilization rise and fall. Are all civilizations doomed to inevitably rise and fall? Do all collapse? Let Greg explain.

In repatriation news, ArtNews notes that the Yale Peabody Museum has identified human remains and eight funerary objects to repatriate to the Wabanaki Nations of Maine. And in France, ancient artifacts from Ethiopia were finally given back in a diplomatic ‘handover.’ However, The Art Newspaper also notes that “On the restitution front, meanwhile, there is frustration about the lack of progress since President Emmanuel Macron of France announced his revolutionary plan to return African heritage to the continent in November 2017. No date has yet been fixed for a bill on colonial items to be debated in the French National Assembly.”

In addition, it was reported this week that the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University has said that they will return the Thirumangai Alwar bronze idol to Tamil Nadu” (southern India). And over at NPR’s “All Things Considered”, art historian Elizabeth Marlowe discusses the return of a bronze head of Septimius Severus to Turkey from the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen.

Over two weeks ago, Brown University announced that they would transfer land in Bristol (Rhode Island) to the trust of the Pokanoket tribe. “The transfer of 255 acres of Brown’s Mount Hope property will ensure its preservation as well as sustainable access by Native tribes with ties to its historic sites, and the remaining 120 acres will be sold to the Town of Bristol.” Brown is the first Ivy League school to return native lands, but it shouldn’t be the last. The BBC also has a good article on “How New York City is reclaiming its Native American roots,” with an important mention of the famed Mohawk ‘Skywalkers’ that helped to create the NYC skyline with their ironworking.

Let us turn to museum exhibition reviews. At Ancient Jew Review, leading historian of ancient and medieval Judaism Simcha Gross addresses the “stunning exhibition on Elephantine [Egypt] currently hosted at the James-Simon-Galerie and the Neues Museum in Berlin.” Then, Phoebe Joyce reviews the British Library’s astonishing new exhibition Medieval Women: In Their Own Words for Modern Medieval. Finally, the New York Times reviews The Met’s epic “Flight Into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876 — Now.” The Spotify playlist that goes with this exhibition is straight fire 🔥 (with a little Earth and Wind to boot).

In Beijing at the beginning of November, the first ever World Conference of Classics kicked off. From Zhang Zhiqiang, director of the Institute of Philosophy at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, commenting on the Chinese School of Classical Studies in Athens to Tim Whitmarsh, a Fellow of the British Academy and a Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge in England, serving as a keynote speaker, it is great to see global antiquity taking root.

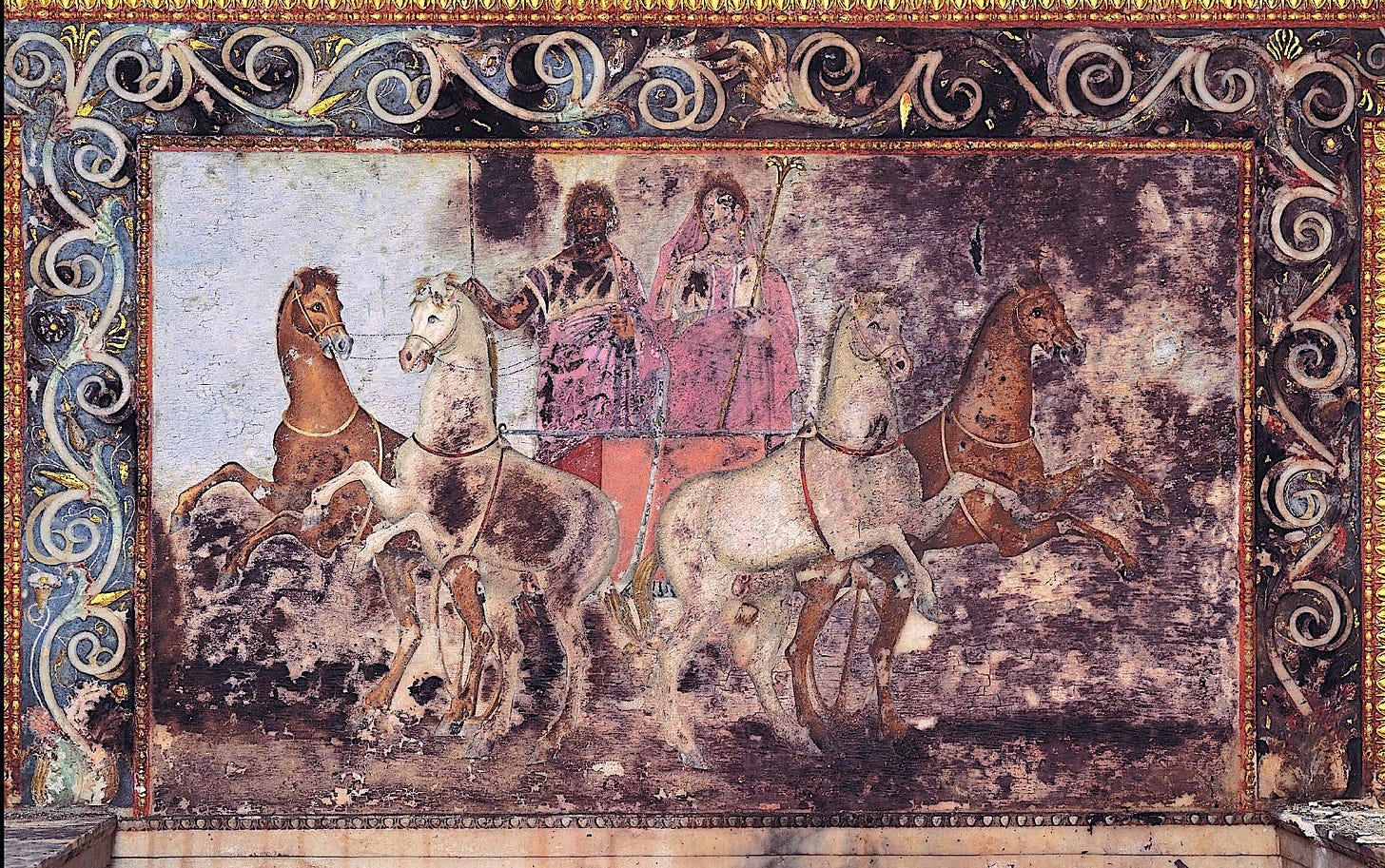

Finally, polychromy specialist Mark Abbe and reconstructive artist Stephen Chappell have been working with the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University to try and reconstruct the Severans using microscopic pigment remaining on two busts of Septimius Severus and Julia Domna. In her review of Gladiator II, Sarah Bond discusses them. And read more in the museum’s new volume Imperial Colors: The Roman Portrait Busts of Septimius Severus and Julia Domna (2023) As far as the movie goes, take a look at Bret Devereaux’s splendid Gladiator II review for Financial Times for more on the film.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Dead Sea Discoveries Vol. 31, No. 3 (2024) Travel and Transformation in Early Judaism

Near Eastern Archaeology Vol. 87, No. 4 (2024)

Aitia Vol. 13, No. 2 (2023) #openaccess

Noctua Vol. 11, No. 3 (2024) #openaccess

Mélanges de l'École française de Rome - Antiquité Vol. 136, No.1 (2024) #openaccess Studi su Ostia e Portus: Settimo seminario Ostiense

Gerión. Revista de Historia Antigua Vol. 42 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess

American Journal of Philology Vol. 145, No. 3 (2024)

Journal of South Asian Intellectual History Vol. 6, No. 2 (2023) NB Bruno M. Shirley “Towards an Intellectual History of Cakravartin Kingship”

Journal of Indian Philosophy Vol.52, No. 5 (2024)

Journal des Médecines Cunéiformes No. 41 (2023) #openaccess

Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft Vol. 19, No. 1 (2024) NB Simon Clay “Lilith, a Monster Feminist Icon: Four Genealogies of a Divine Jewish Demon”

Anais de Filosofia Clássica Vol. 17, No. 33 (2023) #openaccess Filosofia Clássica Chinesa

Faventia Vol. 46 (2024) #openaccess

Circe, de clásicos y modernos Vol. 28 No. 2 (2024) #openaccess

Vivarium Vol. 62, No. 4 (2024) NB C. Philipp E. Nothaft “Peurbach’s Precursors: Notes on the Early History of the Ptolemaic-Aristotelian Compromise in Latin Astronomy”

Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia Vol. 30, No. 2 (2024)

Auster Vol. 29 (2024) #openaccess

Lingue antiche e moderne Vol. 13 (2024) #openaccess

Mnemosyne Vol. 77, No. 7 (2024) NB Claudia Zatta “‘Is the Embryo a Living Being?’ (Aët. 5.15): Embryology, Plants, and the Origin of Life in Presocratic Thought”

Classical World Vol. 118, No. 1 (2024) NB Helena López Gómez “Violence Against Women of the Roman Imperial Household: Examples of Gender-Based Violence?”

Religion in the Roman Empire Vol. 10, No. 2 (2024) Law: Textual Representations and Practices in the Ancient World

Journal of Buddhist Philosophy Vol. 6 (2024)

Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 85, No. 4 (2024) NB Alexander D. Batson “Sinai and the Areopagus: Philip Melanchthon, Natural Law, and the Beginnings of Athenian Legal History in the Shadow of the Schmalkaldic War”

Maarav Vol. 28, Nos 1-2 (2024)

Phoenix Vol. 77, Nos. 3-4 (2023) Epic Heroism in Late Antiquity

Early Christianity Vol. 15, No. 3 (2024) Tatian's Diatesseron: New Inquiries

Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies Vol. 64 No. 4 (2024) #openaccess

Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic Online Vol. 8 (2024) #openaccess

Revue d'Histoire des Textes Vol. 19 (2024) NB Birger Munk Olsen “Chronique des manuscrits classiques latins antérieurs au xiiie siècle – VII”

Manuscripta Vol. 67, No. 2 (2024)

Revue d'Etudes Augustiniennes et Patristiques Vol. 70, No. 1 (2024)

Emerita Vol. 92 No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

Lectures, Workshops, and Exhibitions

On Friday, December 7, 2024 at Noon EST. Dr. Peera Panarut, Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, Universität Hamburg, and 2023-2024 SIMS Visiting Research at Fellow at the University of Pennsylvania will lecture on the “Peculiar Paracontents from Thai Chanting Books: A Case Study of Manuscripts from Philadelphia.”

December 10, 2024 at 4:00 pm CET marks the next zoom talk in the online lecture series Rethinking Social Contention in the Pre-Modern Islamicate World. Medieval Islam expert and translator Philip Grant, who will examine the Zanj rebels of 9th-century Iraq in a talk entitled 'Was the Zanj Rebellion a 'Slave Revolt'?' If you'd like to attend, simply send a message to the team email: score.aai@uni-hamburg.de.

December 11, 2024 at 5:30 ET, ISAW-NYU’s Expanding the Ancient World Workshop series has a great zoom workshop prepared on “Navigating Early Indian Ocean Trade: A Resource for World History Teachers”, led by Priya Barchi (PhD Candidate, ISAW). The workshop is part of a “series of professional development workshops and online resources for teachers…This workshop offers a deep dive into the maritime trade networks of the Western Indian Ocean from the 1st to the 5th century CE.” Registration is required at this link.