This week, scholar and YouTuber Andrew Mark Henry discusses academics creating digital content through YouTube, podcasts, and other popular media. Then, we look at the discovery of the earliest known bronze Buddhas, the role of Ancient Rome in the “Black Avenger” motif, questions surrounding the Sodom & Gomorrah asteroid article, and more…

Scholars as Content Creators (Andrew Mark Henry)

“Public scholarship” has become something of a buzzword in the academy over the past few years. If you’re a scholar who writes books for a popular audience, produces a podcast, or is active on Twitter, you are dubbed a “Public Scholar.” But I’ve always found this term a little idiosyncratic, mostly because it’s an insider’s term unique to academics. To everybody else, you’re a “content creator.” I think public scholars can embrace this identity and all that it entails.

From my experience running a YouTube channel, scholars can be excellent content creators, as demonstrated by the state of religious studies educational content on YouTube. Seven years ago when I launched my YouTube channel “Religion for Breakfast,” there was very little content available on the platform about religion taught from a scholarly perspective. No other YouTube channel was dedicated to religious studies. But now there is a cohort of scholarly religious studies YouTubers reaching tens of thousands of viewers. Kaitlyn Ugoretz recently launched “Eat, Pray, Anime,” a channel dedicated to Japanese religion and pop culture. Angela Puca runs “Angela’s Symposium,” where she publishes videos about contemporary paganism and demonology. Filip Holm runs the world religions variety channel “Let’s Talk Religion”, and Justin Sledge publishes videos about theosophy, mysticism, magic, and alchemy on his channel “ESOTERICA”.

All of these YouTubers have graduate training in religious studies, and our graduate training makes us better content creators. Academic YouTubing is basically a form of translation, translating scholarly publications for a public audience.

Prepare for the Attention Economy:

What graduate school didn’t prepare me for is the reality that all content creators face online: The Attention Economy. This is the idea that “attention is the currency of the Internet.” Many media analysts have made this observation, so this is not a unique thought of mine, but it’s an important lesson to learn for any scholar who wants to dive into content creation. As far as social media companies are concerned, the ability to grow an audience and hold that audience’s attention is the true source of value in a capitalistic sense. This is why platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and others are designed specifically to hack your attention and keep you on the platform. This also negatively incentivizes content creators to produce click-baity or sensationalist content.

What does the attention economy mean for scholarly content creators? It means the “marketplace of ideas” is a farce. The best, most rigorous, and most peer-reviewed ideas do not naturally float to the top. Rather, the ideas that best capture an audience’s attention float to the top. Scholarly content creators must then work to find and foster an audience in addition to producing excellent content. To that end, I’ve found the cohort model on YouTube to be effective. While the first few years of building my YouTube channel was slow, the current cohort of religious studies YouTubers offers many more opportunities for collaborations and sharing audiences.

The best way forward for scholarly content creators may be to grow online networks like this on particular platforms to help amplify academically-sound content to the widest possible audience.

Seen on the Web

The earliest known bronze Buddha statues have been found in China’s northwestern Shaanxi province. The statues were discovered within a six-tomb family cemetery of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 CE); one is for Sakyamuni (Gautama Buddha) and the other for the Five Tathāgatas.

This week, in posts on the SCS Blog and on Sententiae Antiquae, Javal Coleman wrote on racism in antiquity and then on Lucilian satire.

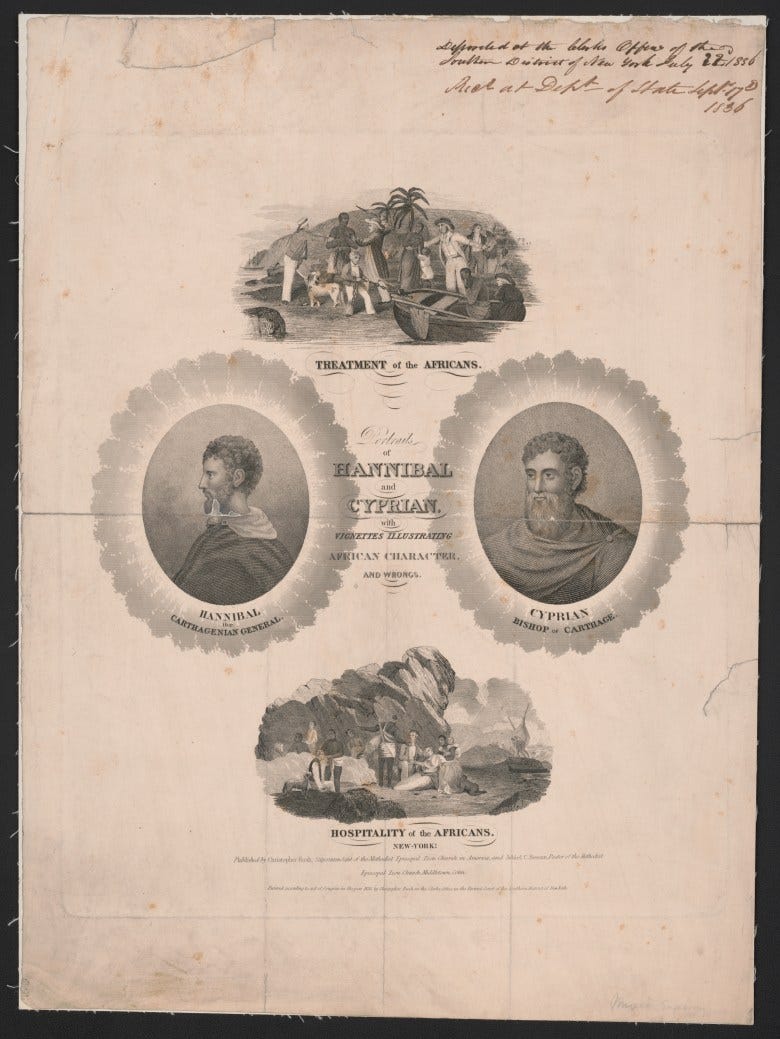

Over at Hyperallergic, Sarah E. Bond published an essay on a number of new books looking at how the myths of Ancient Rome (e.g. Lucretia, Spartacus, Hannibal, Cato) influenced the early modern mythologies created by playwrights and abolitionists—and how this influenced European messaging surrounding the Haitian Revolution.

The Los Angeles Review of Books has published a revealing essay on “Donna Tartt’s “The Secret History” as Revenge Fantasy”, written by poet Brooke Clark. It takes a look at Lili Anolik’s podcast, Once Upon a Time … at Bennington College, and investigates Tartt’s book as compared to the Classics world on campus.

In an interview with Erika Valdivieso, she reveals her current research interests and what inspired her to study antiquity:

Like many Peruvian families, our house was decorated with reproductions of Inca, Chimú, and Moche artifacts. For me, these pre-Columbian civilizations were ancient, and it was only later that I learned about Greeks and Romans. Growing up with these different frames of antiquity made me curious about points of contact between these worlds, which in turn led me to the colonial period.

Valdivieso is currently preparing manuscripts on “Classical currents in Quechua Theater: Espinosa Medrano’s El robo de Proserpina” and another on “Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia and colonial Peru.”

On Retraction Watch, that specious and controversial journal article in Scientific Reports that implied that the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah was a retelling of the aftermath of an exploding asteroid (circa 1650 BCE) is still being heavily questioned. And in a new piece by Morag M. Kersel, Meredith S. Chesson, and Austin "Chad" Hill in Sapiens, the authors elaborate on the looting directly related to this type of Biblical pseudoscience.

In other news, Anne Carson continues to peer into the depths of our souls.

Upcoming Lectures and Conferences

ASU’s #RaceB4Race is back from January 28-29, 2022 with a focus on poetics:

New Online Journal Issues curated by @YaleClassicsLib

Thiasos Vol. 10, No. 2 (2021) #openaccess Offerte in metallo nei santuari greci. Doni votivi, rituali, smaltimento

Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete Vol.67, No. 2 (2021)

Rhizomata Vol. 9, No. 2 (2021) Attention in Ancient Philosophy

Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt Vol. 57 No. 1 (2021)

Byzantinische Zeitschrift Vol. 114, No. 4 (2021) Bibliographische Notizen

Karanos Vol. 4 (2021) #openaccess

Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum Vol. 25, No. 3 (2021)

Metropolitan Museum Journal Vol. 56 (2021)

Dialogues d'histoire ancienne (2021) Supplément 24 Une République impériale en question?

Gerión Vol. 39, No. 2 (2021) #openaccess Contextos del priscilianismo (Gallaecia, siglos IV-VI)

Britannia Vol. 52 (2021)

New Testament Studies Vol. 68, No. 1 (January 2022)

Hesperia Vol. 90, No. 4 (October-December 2021) NB: “Disability and Infanticide in Ancient Greece” by Debby Sneed

The Journal of Roman Studies Vol. 111 (2021)

Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 55 (2021) NB: “Citizenship Discourses in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages” by Els Rose

Journal of Ancient History Vol.9, No.2 (2021) NB: “Emasculating healers. Medical castration practices in Greco-Roman antiquity” by Jacqueline G. M. König

Gnomon Vol. 93, No. 2 (2021)

Altorientalische Forschungen Vol. 48, No. 2 (2021)

Philologus Vol. 165, No.2 (2021) NB: “Why Humans Do Not Cast Off Old Skin Like Snakes. Knowledge and Eternal Youth in Nicander’s Theriaca” by Olga Chernyakhovskaya

Klio Vol. 103, No. 2 (2021)

Pitches

The Public Books section "Antiquities" continues to take pitches for articles to be published in early 2022. You can also pitch to our “Pasts Imperfect” column at the LA Review of Books using this form. Thanks for reading!

Since its inception, I have been finding Pasts Imperfect to be adept at finding a good balance in presenting good scholarship in terms accessible and attractive to broad public. Kudos for that! However, I find the advice offered in this installment worrisome.

Embracing the identity of 'content provider' rather than 'public scholar' is not good advice... well, it may be good for capturing a few milliseconds of attention from a few more sets of eyes, but it is not good for scholarship. It makes one complicit in the commodification of education, which is the subversion of education. It leads inexorably to clickbaiting, sensationalism, presentism, and dumbing-down of 'content' for the lowest common denominator in the viewing public. The balance I praised in my first sentence depends on recognition that the 'widest possible audience' online is too wide. The scholarship part of 'public scholarship' still requires a public willing to read and think beyond sound-bites and dazzle. Such a public can be cultivated and expanded over time, but not by embracing worst imperatives of the Internet economy.