Pasts Imperfect (11.30.23)

Ancient & Modern Indigeneity, Napoleon in Egypt, Uto-Aztecan Language Migration, and More

This week, ancient religion scholar and member of the Choctaw Nation, Chris Hoklotubbe, addresses ancient and modern Indigeneity in readings of the Bible. Then, a Scottish schoolboy goes looking for potatoes and finds Egyptian antiquities, reproducing Tyrian purple, ancient DNA and the linguistic diversity of California, using Indigeneity as a framework for teaching ancient history, a new brew with an ancient African grain, new ancient world journals, and much more.

Ancient Ethnic Hierarchies & Indigenous Readings of the Bible by Chris Hoklotubbe

What might an Indigenous perspective bring to interpreting the ancient Mediterranean world? As a scholar of the New Testament in its ancient Greek and Roman contexts as well as a member of the Choctaw Nation, I’ve been considering how the cultural insights of my Indigenous heritage might contribute a fresh perspective on classical texts that may have been underappreciated by interpretations framed by predominantly by Western and often Christian experiences. For example, Christian colonizers’ interpretations of Indigenous peoples as barbaric and wild might frame an interpretation of the racially charged rhetoric of The Letter to Titus: an early second-century CE pseudepigraphal text ascribed to Paul of Tarsus.

Consider this story from my own nation that illustrates this point well. In Elliot, Mississippi—which in 1820 belonged to the Choctaw Nation—the tribal chiefs or mingos gathered together. On this particularly humid Southern day, they sought to examine the progress of young Choctaw students who were studying the Holisso Holitopa (Holy Book, or the Christian Bible) and learning essential skills of reading and writing that would help them navigate the changing chaotic world, under the direction of the Presbyterian missionary Cyrus Kingsbury.

This meeting would quickly turn sour. After showing off the progress his Indigenous students had made, Rev. Kingsbury lamented the “evils” that had befallen the Choctaws due to their excessive drinking of whiskey. If only the Choctaws would quit the bottle, he sighed, their people could make so much progress in their collective education and civilization. Upon hearing his complaint, one of the chiefs, mingo Mushulatubbee—who may or may not be my ancestor according to my grandfather—retorted: “I can never talk with you good missionaries without hearing something about the drunkenness and laziness of the Choctaws. I wish I had traveled over the white man’s country, then I would know whether my people are worse than every other people.”

Ethnocentrism and paternalism have long characterized Christian missionaries' attitudes toward potential Indigenous converts, perceiving them to be lazy, gluttons for alcohol, and uncivilized. Should we be surprised to find similar rhetoric in The Letter to Titus? The author, writing as Paul, asks “Titus” to recall that he had directed Titus to appoint elders across Crete with exemplary character who could teach and defend the “trustworthy word” and “sound teachings” against barbaric naysayers (Titus 1:5–9). The author then describes such Cretan contrarians as follows:

For there are also many insubordinate people, idle talkers and deceivers, especially those from the circumcision [faction]; whom it is necessary to silence, since they are overturning entire households, teaching what they should not for the sake of shameful profit. One of them [Cretans], their very own prophet, said, “Cretans are always liars, evil beasts, lazy gluttons.” This testimony is true! For this reason rebuke them sharply, so that they may become sound in the faith, not giving heed to Judean myths or to commandments of those who reject the truth (translation my own).

Contemporary biblical scholars have generally waved away the idea that Paul resembles a modern bigot. They either posit that the author must have been justified in his use of available ethnic stereotypes to characterize Cretans or that the author is making an allusion to the “Liar’s Paradox” to insinuate that the opponents are philosophical charlatans.

But when we take global Indigenous experiences into account, such uses of stereotypes to denigrate others is exactly what we expect to find in both missionary discourse as well as among ethnic groups competing against other ethnic groups for limited cultural prestige and resources in colonial/imperial contexts. As Franz Fanon and many sociological studies have observed, educated members of subjugated groups critique hierarchies of ethnic groups in order to secure the social position and capital of their own group at the expense of others. Such ethnic hierarchies are informed by values esteemed among the dominant colonial-imperial in-group, in whose eyes subordinated ethnic groups compete against one another for colonial-imperial favor.

Despite knowing very little about the actual anonymous author of Titus, both he and his earliest audiences were considered among the mistrusted and potentially seditious subordinate groups within the Roman Empire. Early Christ-adherents also had to compete against other ethnic groups and cultural minorities for limited cultural prestige and socioeconomic advantages. Philip Harland has demonstrated how ancient Judeans living roughly a generation or two prior to the author of Titus, namely Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 B.C.E.–50 C.E.) and Josephus (c. 37–95 C.E.), adopted and subverted elements of Greek and Roman ethnic hierarchies in order to elevate the status of Judeans in the eyes of Romans at the expense of rival Egyptians.

In my recent article, I argue that the author of Titus denigrates Cretans and Judeans using recognizable ethnic stereotypes in an attempt to elevate their own sense of social standing along a social-political ethnic ladder. The author goes on to represent Christ-followers as embodying the best of whatever cultural values Romans may have respected among Greek and Judean peoples, including their cultural knowledge (paideia) and covenant relationship to divine power, respectively. He constructs a positive “civilized” image for his audience to imagine themselves embodying that could have served a number of social and psychological needs including: increasing their self-esteem, providing fodder for proselytizing and homilies, or simply helping to them to “pass” as respectable members of a society that often held them in suspicion.

Indeed, my ancestors among the Choctaw Nation were similarly concerned with “passing” as civilized and virtuous neighbors, leading many to appropriate American values and lifeways. They even allied with U.S. forces against other competing Native peoples, including Tecumseh’s confederacy and many Muscogee/Creeks in the Red Stick War. Alas, despite their efforts, their ancestral homelands in Mississippi would be too enticing for American ambition and the Choctaws would be dispossessed from their lands by dishonorable U.S. agents.

When I imagine what might lie ahead for Indigenous interpretations of the ancient Mediterranean world, I’m excited by the possibilities of fresh readings. There is so much more work yet to be done by scholars in Classics from underrepresented ethnic groups to consider how cultural heritages provide useful theoretical frameworks and lenses for interpreting the ancient Mediterranean world afresh.

Bibliography on Indigineity curated by T.J. Tallie

Tallie, T.J. “Indigeneity, Movement, and Disrupting the Global Nineteenth Century,” in World Histories from Below, by Antoinette Burton and Tony Ballantyne, Bloomsbury Press, 2022.

Arvin, Maile. Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai`i and Oceania. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2019.

Chang, David A. The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration. 1st edition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Flint, Kate. The Transatlantic Indian, 1776–1930. Illustrated edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Fullagar, Kate and Michael A. McDonnell, eds. Facing Empire: Indigenous Experiences in a Revolutionary Age. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

Jackson, Shona N. Creole Indigeneity: Between Myth and Nation in the Caribbean. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Standfield, Rachel, ed. Indigenous Mobilities: Across and Beyond the Antipodes. Canberra: ANU Press, 2018.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

Sometimes the headlines write themselves. At Artnet, Jo Lawson-Tancred explains “How a Scottish Schoolboy Digging for Potatoes Uncovered a Trove of Egyptian Antiquities.” And no, he did not think that the giant red sandstone head was a spud destined for the dining hall. Surprise! There were 15 more objects buried on the property. The discovery is perhaps a testament to the widespread (and often specious) collection of Egyptian antiquities by wealthy Europeans in the 19th century.

Over at the BBC, Zaria Gorvett discusses mucousy snails. I mean, rotting marine flesh. I mean, the stench of fermented urine. No, I’m talking about Tyrian purple, which consulting manager—and dyemaster—Mohammed Ghassen Nouira is trying to reproduce. I don’t know about you, but after reading this article, I’m tempted to gobble my way through some spicy Tunisian murex pasta.

If you are tired of your relatives’ bigotry at the Thanksgiving table, maybe you sprinted your way to the nearest cinema and saw Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, which hit theaters November 22. In it, the titular character fires his cannons at the pyramids of Giza—but the New York Times’ Becky Ferreira is quick to remind us that the real Napoleon held off. He didn’t shoot the nose off of the Sphinx, but he sure did pillage his fair share of Egyptian patrimony, like the Rosetta Stone.

A new study in Nature led by Nathan Nakatsuka, Brian Holguin, Jakob Sedig, et al., examines the ancient genomes of a 119 individuals from California and Northern Mexico. “Genetic continuity and change among the Indigenous peoples of California” asks why “California harboured more language variation than all of Europe.” The researchers then argue that this linguistic diversity can in part be explained by northward migrations about 5200 years ago that spread Uto-Aztecan languages prior to the “dispersal of maize agriculture from Mexico.” In a final note, the authors remark on the need to work with indigenous communities in all future studies. It is a best practice for all those working on these issues and using ancient DNA analysis:

It is important to carry out such research in a way that is engaged with present-day Indigenous descendant groups, following approaches such as those taken in this and previous studies, and informed by recent discussions and recommendations concerning ethical analysis of DNA from ancient Indigenous individuals.

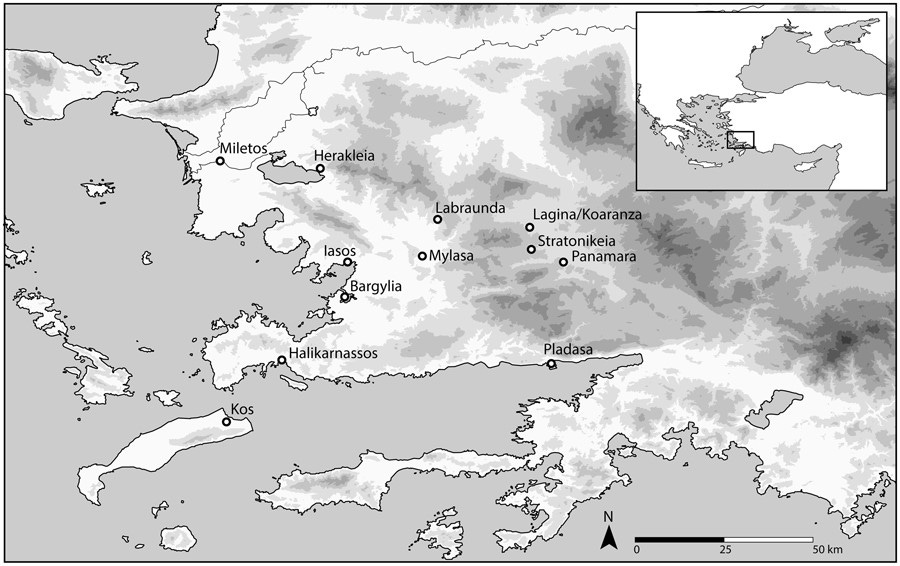

Over at the American Historical Review, Hellenistic historian Jeremy LaBuff discusses teaching and publishing about antiquity through a framework of Indigeneity. His case studies all come from ancient Karia (modern Turkey) during the Hellenistic era.

Global forms of colonialism in the Hellenistic world were often quite different from modern settler colonialism, but they still privileged Macedonians, and to a lesser extent Greeks, who were better positioned (at least initially) to align with the forces of imperialism, even if most Greeks ended up in conditions of subjection relatively similar to those of non-Greeks

LaBuff changed his own teaching in his home state of Arizona. He also views the framework of Indigeneity as a way of connecting the past and the present in nuanced, pivotal ways for our students, our field, and the public: “[Indigeneity] promises to differentiate the victims of colonial regimes and predicts diverse indigenous experiences, perhaps even in modern contexts.”

In the The New Yorker, evolutionary biologist and anthropologist Manvir Singh thinks it is time to “Rethink the Idea of the Indigenous.” Singh asks a number of important questions about the globalization of the category:

Indigeneity is powerful. It can give a platform to the oppressed. It can turn local David-vs.-Goliath struggles into international campaigns. Yet there’s also something troubling about categorizing a wildly diverse array of peoples around the world within a single identity—particularly one born of an ideology of social evolutionism, crafted in white-settler states, and burdened with colonialist baggage. Can the status of “Indigenous” really be globalized without harming the people it is supposed to protect?

You can also listen to a podcast of the article here, with Singh adding to the conversation alongside editor Tyler Foggatt.

Senegalese-born chef Pierre Thiam is making headlines for his use of fonio, a West African grain that has been cultivated for over 5,000 years. In an epic anecdote, The Guardian speaks to Thiam about that time he met Garrett Oliver, the brewmaster of Brooklyn Brewery, at a party hosted by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson in 2018. I never thought my love of The Roots, beer, and climate-friendly grains would come together in such a nice beverage, Fonio Rising.

At the TangentCast, Mario Telò discusses his book, Resistant Form: Aristophanes and the Comedy of Crisis, which is able to be downloaded for free from Punctum Books.

In the Collège de France’s Books and Ideas Pierre-Marie Morel reviews Aurélien Robert’s Épicure aux Enfers. Hérésie, athéisme et hédonisme au Moyen Âge (Fayard, 2021) which demonstrates the continued presence and partial rehabilitation of Epicurus in the Latin Middle Ages.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Orientalistische Literaturzeitung Vol. 118, No. 3 (2023)

Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum Vol. 27, No. 3 (2023) NB Philipp Niewöhner, “Diversity in Late Antique Christianity: The Cultural Turn, Provincial Archaeology, and Church Building.”

Elenchos Vol. 44, No. 2 (2023) NB Anna Corrias “Plotinus on the Daemon as the Soul’s Erotic Disposition towards the Good”

Revue des sciences philosophiques et théologiques Vol. 107, No. 3 (2023) Obéissance et autorité au Moyen Âge

Medieval Encounters Vol. 29, No. 5-6 (2023) Ties of Kinship and Islamicate Societies

Slavery & Abolition Vol. 44, No. 3 (2023) Slavery in Byzantium and the Medieval Islamicate World: Texts and Contexts

Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology Vol. 10, No. 3 (2023) #openaccess

Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica Vol. 29, No. 1 (2023) #openaccess

Libyan Studies Vol. 54 (2023)

Early Science and Medicine Vol. 28, No. 3-5 (2023) Complexio Across Disciplines

Frankokratia Vol. 4, No. 2 (2023)

Classical World Vol. 117, No. 1 (2023) Women’s Voice in the Early Roman Empire

Britannia Vol. 54 (2023)

Journal of Greek Linguistics Vol. 23, No. 2 (2023) #openaccess

Atlantís - review No. 54 (2023) #openaccess

CALÍOPE: Presença Clássica vol. 44 (2022) #openaccess

International Journal of the Classical Tradition Vol. 30, No. 4 (2023)

Comitatus Vol. 54 (2023)

Studies in Late Antiquity Vol. 7, No. 4 (2023)

Revista de Literatura Medieval Vol. 35 (2023)

Papers of the British School at Rome Vol. 91 (2023) NB Rosamond McKitterick “Roman Books and the Papal Library in the Early Middle Ages”

Dao Vol. 22, No. 4 (2023) NB Jordan Palmer Davis “Sympathy, Resonance, and the Use of Natural Correspondences in Philosophical Argument: A Comparison of Greco-Roman and Early Chinese Sources”

Hermes Vol. 151, No. 4 (2023)

Online Lectures, Events, and Exhibitions

On Friday, December 1, 2023 from 1:10 pm to 4:00 pm ET, Katherine Harloe will discuss “Reading Winckelmann's Love Letters Across Classical and Vernacular Literary Canons” for the UTM Annual Classics Seminar (UTMACS). Contact Martin Revermann (m.revermann@utoronto.ca) for the meeting link.

On December 6, 2023, Jana Matuszak speaks on “Law and Morality in Sumerian Satirical Tales” for the The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures. ISAC notes: “Ancient Iraq is famous for producing the world’s earliest compilations of casuistic law; the Laws of Hammurabi being the most renowned example. But what happens when a legal problem occurs that has not been considered by royal legislation? Two Sumerian short stories raise potentially subversive questions – and provide surprising solutions.” This lecture is presented in connection to the special exhibition, Back to School in Babylonia.”

From now until January 29, 2024, the Getty Villa in Los Angeles hosts The Egyptian Book of the Dead. The exhibition is presented in Spanish and English.

The “Uncovering Abydos” hybrid conference from the EES will commence December 5-7, 2023. It is “A symposium on the history and significance of 125 years of archaeological excavations (1899-2024)” organized by Amany Abd El Hameed, as well as Hisham El Lithy, Mohammed Gamal Rashed, Robert Vigar, and Essam Nagy. You can book attendance here.

Got an idea for PI’s next post? Pitch themes and suggestions by replying to this email. We pay writers!

Thanks , always love to hear from you and the latest news of antiquities from new angles. Getting news about the Ufos I wonder whether you have any antique/Indian speculationsm documents or pics of t hat? I am also very curious of the mitra interior, i e in the Egyptian mold, also the antenna looking feathers on top of Queen Ties head. Possibly electricity receivers, or other?