Pasts Imperfect (11.2.23)

Stoicism in Late Capitalism, Medieval Tattoos, Bronze Age Scripts, and More

This week, Joel Christensen discusses the widespread obsession with Stoicism in Corporate America and Silicon Valley. Then, medieval tattoos in Ghazali, new open access books (one on Bronze Age Aegean scripts and another on the Christianization of knowledge in Late Antiquity), Greco-Roman queer icons, documenting Indian artifacts to halt smuggling, new ancient world journals, and more.

The Unnerving Renaissance of Stoicism in Late Capitalism by Joel Christensen

Last spring my family and I were visiting old friends who are definitely among the winners of the professional class. The husband has risen to the top of his field and, not coincidentally, is coming within sight of that “eff-you money” the show Billions has made popular. For years, my academic career and my work has been a mystery to this couple—the kind of thing accepted as a bit eccentric, but ultimately harmless: save for the paltry salary it earns compared to other professionals.

Near the end of a long dinner, though, the husband asked me what I thought of Marcus Aurelius. The emperor? I thought. But no, our friend was asking about the capital-P Philosopher. He wanted to know more about him, as well as Epictetus and Seneca. Then he asked me if I knew Ryan Holiday and The Daily Stoic. Was I ever thankful the kids around the table were getting restless.

Stoicism has been having something of a renaissance in the United States since the 1990s, accelerated by a particular kind of marketing aimed at a particular type of American consumer. As Gregory Hays writes in the New York Review, some of this popularity can be traced to James Stockdale’s memoir on how the doctrines of Epictetus supported him during his time as a POW in Vietnam. In Hays’ reading, Tom Wolfe’s novel A Man in Full brought Stoicism to a mainstream audience in the late 1990s followed by a series of translations aimed at wider audiences.

But the Silicon Valley crowd has also supercharged Stoicism in our new gilded age. A narrow set of what I would consider “manly ideals”—in the sad tradition of Harvey Mansfield’s absurd treatise Manliness—have come to characterize a kind of “prosperity Stoicism” that apes actual philosophy the way that the Prosperity Gospel twists Christianity.

Now, some of these tenets sound fine: controlling emotions and appetites, accepting that external reality is beyond your control, and limiting your wants. But ultimately, these values show up in controlling money and building wealth. The news articles that laud our plutocrats make slight work of Stoicism, to be honest, with one article claiming that billionaires succeed by “staying humble and knowing that we don't know everything.” There’s little in such bromides for understanding moral complexity. Instead, we get advice to “live below your means” (avocado toast is why you can’t afford a mortgage!) or “ruthlessly protect your time.”

A large part of what I find disturbing about modern Stoicism is its relentless emphasis on the individual and not the community. This is not necessarily intrinsic to Stoicism, but it is essential to the 21st-century self-help market that has grown up with outlets like the Daily Stoic. Modern Stoicism is about taming the self on the way to worldly success, something that might be chanted by Tom Cruise’s character Frank T. J. Mackey in the 1999 Film Magnolia, if he were not wholly dedicated to being a proto-Incel.

Anyone who has read Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, Seneca, and even Cicero will understand that they did care for their communities, if we take their political activities into account. Yet philosopher-billionaires choose to excerpt platitudes about being able to endure want, and wealth being an indifferent desire. The irony of Cicero, Seneca, or Aurelius preaching that wealth is an indifferent has been lost on no one, except, perhaps, the purveyors of modern Stoicism.

What bothers me is the commodification of Stoic doctrine as a series of vapid self-help slogans. Scroll through the Daily Stoic’s page or one of its many imitators. The quotations come out of nowhere: they have no attribution to a text or a translator: a Pinterest style presentation attributes to Epictetus, “If someone succeeds in provoking you, realize that your mind is complicit in provocation”; Marcus Aurelius advises “The best revenge is not to be like your enemy”; or Seneca opines “excellence withers without an adversary.” There’s no sense that these lines are part of an argument or a conversation. Instead, they exist as digital koans, imbibed online without reflection or conversation. They are selected to inspire a particular kind of dogged determination, without the wider context of asking the audience to question the base principles of their actions. No, Modern Stoicism is “just another lifestyle brand”, at its best, a pseudo-philosophical appropriation meditated upon for 30 seconds a day (or longer for some). At its worst, it serves to justify the hoarding of massive wealth, while its hawkers are indifferent to the impact it has on the world.

I must confess a long-term antipathy to this kind of Stoicism (Erik Robinson and I lampooned Broicism in Eidolon several years ago.) Among other irritants, the thing that gets under my skin the most is how it mocks actual philosophy, the history of thought, and a real exchange of ideas. As part of a re-education for myself, I spent part of last spring reading through all of Seneca’s letters from beginning to end. What I found most moving about them was a kind of openness to other ideas, which is in part that well-trod Roman eclecticism, but which is also indicative of actual philosophical practice: studying the arguments of others, learning why you believe what you believe, and testing it out by acting in the world.

Seneca frequently quotes deep cuts from the sayings of the ‘rival school’ of Epicurus and from many others as well. His letters are a testament to a life dedicated to thought and, in its final years, one committed to reviewing and understanding one’s own mistakes. Philosophy is a practice, not a commodity; a true Stoic puts it before all else, as Seneca says when he quotes Epicurus with approval: “you must be a servant of philosophy to touch true freedom.”

My real problem with modern Stoicism is that it reduces what should be a dialogue to ahistorical positivisms. As Emily A. Austin writes in her recent guide, Living for Pleasure: An Epicurean Guide to Life (Oxford, 2023), the gap between Zeno’s prohibition against producing coinage and Seneca’s Bezos-level wealth has long invited charges of hypocrisy. But Epicurus did not oppose wealth as much as he opposed greed. Austin argues that Epicurus believed that “material security is necessary for tranquility” while “the Stoics think we need virtue alone.”

I don’t know that Seneca would agree with that, considering this is a man who counsels to consider quod satis est (“that which is enough”). But I do think that any sustained perusal of Seneca or Marcus Aurelius helps us understand that philosophy—like life—is messy and that dogmatic statements appearing in email inboxes are neither the path to virtue or happiness. But, to give the Daily Stoic its due, sometimes they just may be inspiration for a conversation with a friend. And that’s where the important practice begins.

To read more from Joel, check out Sententiae Antiquae or his substack, Painful Signs.

Mosaic Inscription: “We have been born once and there can be no second birth. For all eternity we shall no longer be. But you, although you are not master of tomorrow, are postponing your happiness. We waste away our lives in delaying, and each of us dies without having enjoyed leisure.” (trans. Frischer) —Metrodorus, Sententiae Vaticanae 14.

Public Scholarship and a Global Antiquity

What does it mean to be an “icon” today, and what did it mean 600 years ago? Benedict Carpenter van Barthold tells us what the ancients might have advised us over at The Conversation, in an essay on “How fame has changed for artists since Antiquity.” (Hint: don’t get caught up in all that social media nonsense.)

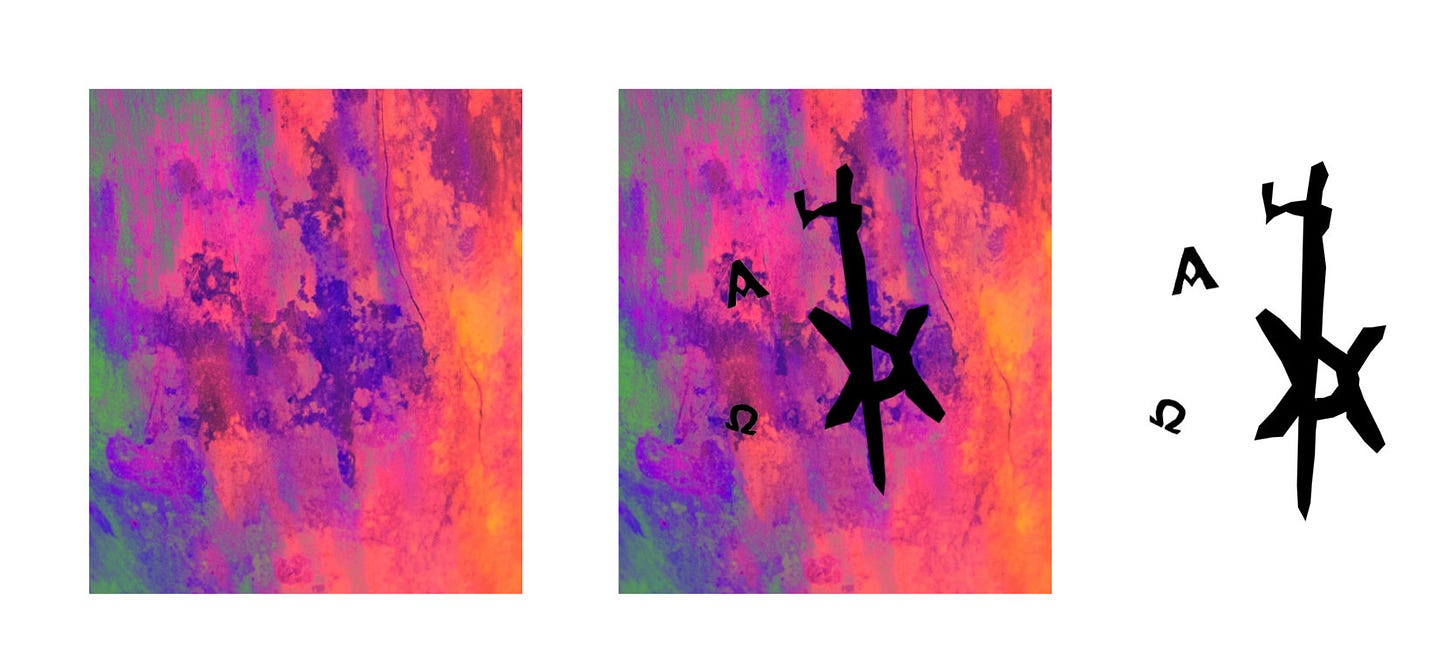

In northern Sudan at the Monastery in Ghazali, a Polish-Sudanese team from the PCMA-UW examined the medieval Christian monastery (7th-13thC CE) there and four surrounding cemeteries. While examining the human remains, a Christogram tattoo was discovered on the right foot of an individual within Cemetery 1. This is reminiscent of the announcement in 2014 that researchers found a Christian tattoo of Saint Michael’s name on the inner thigh of a Sudanese woman from the 8thC CE. For more on this case, see Roberta Mazza’s engaging read, “The girl with the Christian tattoo: Religious-magical practices in late antique Egypt.”

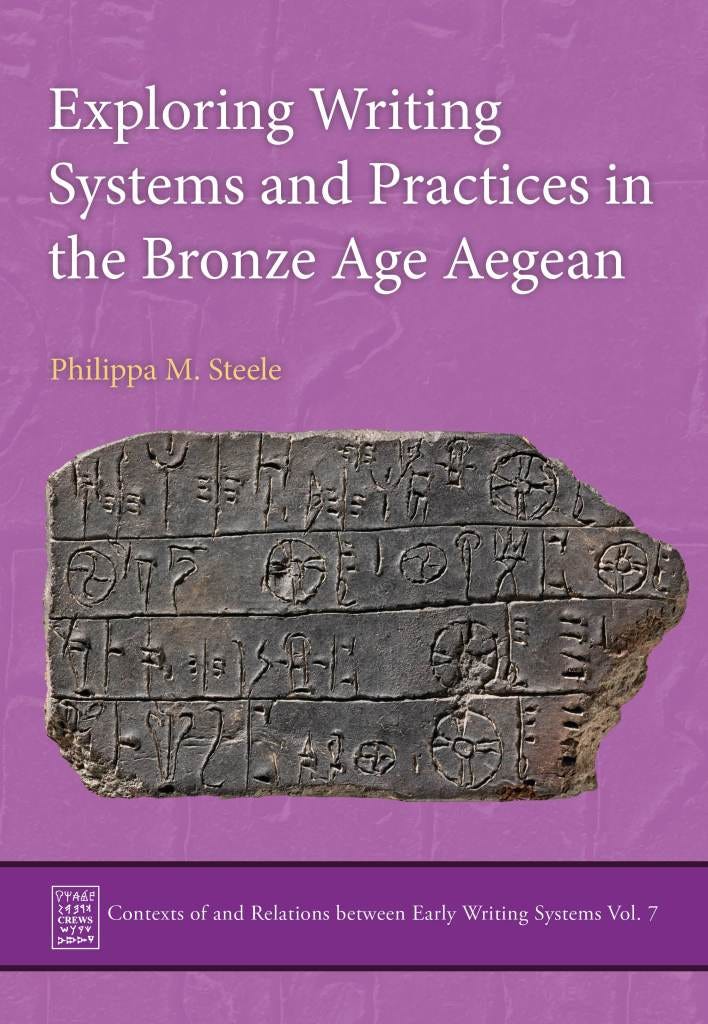

The last open access volume for Contexts of and Relations between Early Writing Systems (CREWS) is out and downloadable. Written by Philippa M. Steele, Exploring Writing Systems and Practices in the Bronze Age Aegean, “looks mainly at the Cretan Hieroglyphic, Linear A and Linear B systems, with a little on their Cypriot cousins too.” Download the book HERE.

Speaking of open access, Mark Letteney’s new book, The Christianization of Knowledge in Late Antiquity, is also free to download. As Cambridge University Press notes, Letteney presents a new approach to asking the question: What does it mean for Rome to become Christian?

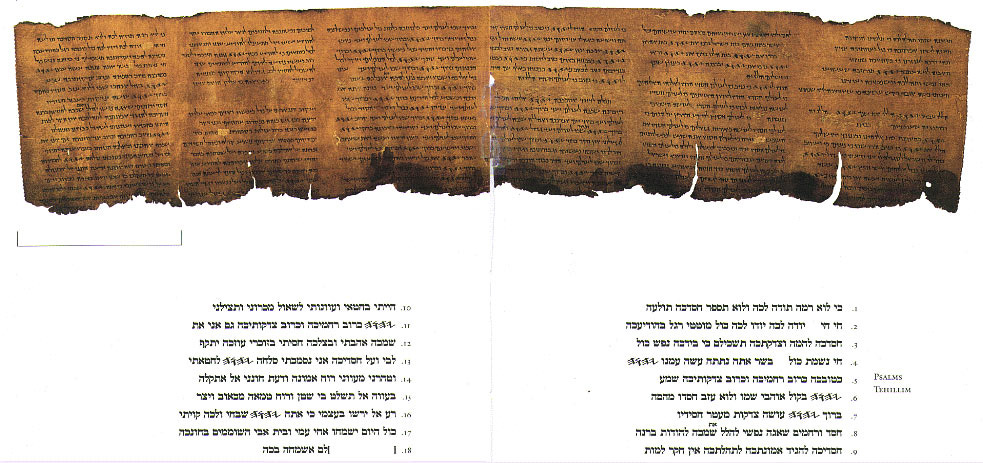

Over at Ancient Jew Review, A.J. Berkovitz discusses his forthcoming book, A Life of Psalms in Jewish Late Antiquity. The book examines late ancient Judaism via the lens of the Psalter. As he notes, “I hope this book encourages others to continue to develop a history of religion that includes its lived dimensions, one that tells the story of the Bible as an object both practiced and preached.”

Surprise, surprise: the ancients were misogynists and thought pregnant people’s bodies were objects! Some things never change. Selena Simmons-Duffin at NPR speaks with University of Oklahoma historian Kathleen Crowther about diachronic metaphors and good old fashioned objectification. And in other areas of ancient medicine, you may want to check out Heidi Marx’s touching and insightful essay on “Pain Management in the Greek and Roman Mediterranean.”

In Chennai, the Archaeological Survey of India’s National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities has put out a statement on the importance of documenting antiquities to prevent their smuggling outside of India’s borders. Director Madhulika Samanta stressed that heritage sites and artifacts were in danger due to a lack of archival evidence. The mission’s goal is to document 5.8 million artifacts and 400,000 sites.

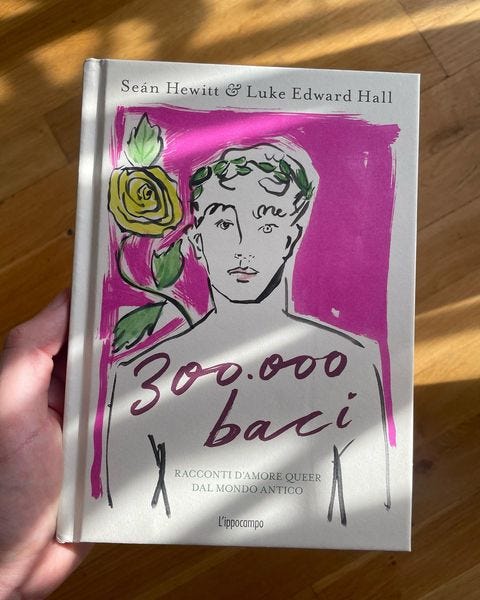

Over at the New York Times, Maggie Lange reports on seven queer icons from Greco-Roman antiquity, compiled by Luke Edward Hall and Sean Hewitt. This is the kind of listicle that I (Stephanie) would have loved to see as a high school Latin student. It would have made Latin Prose so much spicier. The holidays are approaching …

Philaenis [of Martial’s Epigrams] likes working out, drinking and sexually dominating people of all genders.

In a look at the intersection of science, museums, race, and repatriation issues, Christopher Heaney, discusses his recent book Empires of the Dead: Inca Mummies and the Peruvian Ancestors of American Anthropology at the Consortium for History of Science, Technology and Medicine.

A frankly awesome three-part Chinese web film calls for the British Museum to return artifacts. The series is called “Escape from the British Museum” and focuses on a jade teapot (made by Yu Ting in 2011) that comes alive and tries to break free from the museum. It has over 370 million views. The British Museum is home to this real jade teapot, as well as 8,000,000 other objects—of which only 80,000 are on display.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Journal for the Study of Judaism Vol. 54, No. 4-5 (2023) The Septuagint within the History of Greek

Journal of the History of Collections Vol. 35, No. 3 (2023)

‘Atiqot No. 112 (2023) #openaccess Hoard Typology, Function and Purpose in Ancient Societies

Journal of Ancient Philosophy Vol. 17 No. 2 (2023) #openaccess

Journal of Social Archaeology Vol. 23, No. 3 (2023)

Journal of Urban Archaeology Vol. 8 (2023) #openaccess Comparing Urban Heterogeneity

Philosophy East and West Vol. 73, No. 4 (2023)

Phronesis Vol. 68, No. 4 (2023) NB Isabelle Chouinard, “The Cyrenaics on the Premeditation of Future Evils”

New England Classical Journal Vol. 50, No. 2 (2023) #openaccess

Gesta Vol. 62, No. 2 (2023)

Archeologie Sperimentali. Temi, Metodi, Ricerche Vol. 3 (2022) #openaccess

The Medieval Globe Vol. 9, No. 1 (2023)

Aristonothos Vol. 19 (2023) #openaccess

Method & Theory in the Study of Religion Vol. 35 , No. 5 (2023) Special Section on Burton Mack

Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 84, No. 4 (2023) NB Alexandre M. Roberts, “Thinking about Chemistry in Byzantium and the Islamic World

Lectures, Conferences, and Exhibitions of Note

On Thursday, November 2, 2023 (today, y’all), Ellen Muehlberger will be discussing Fayyum Portraits with the Boston Area Patristics Group (BAPG). Email the equally incomparable Andrew Jacobs to get the details and link to the Zoom.

On November 5, 2023 at 7:00 pm in Athens (12pm EST) the British School in Athens will host an online Panel Discussion: “Mythical Retellings: Reimagining the women of Greek Myth.” The panelists are novelist Claire Heywood, Jennifer Saint, and Susan Stokes-Chapman. Edith Hall with chair.

From November 6-7, 2023 the online conference, Law, Religion and Sciences – rules, norms, and the transfer of knowledge in ancient to medieval traditions, will be held via Zoom. It is a part of the research network, Between Encyclopaedia and Epitome – Talmudic strategies of knowledge-making in the context of ancient medicine and sciences. Further information including a poster and a full program with all zoom links are available on the homepage of this conference. It is organized by Lennart Lehmhaus and Mark Geller.

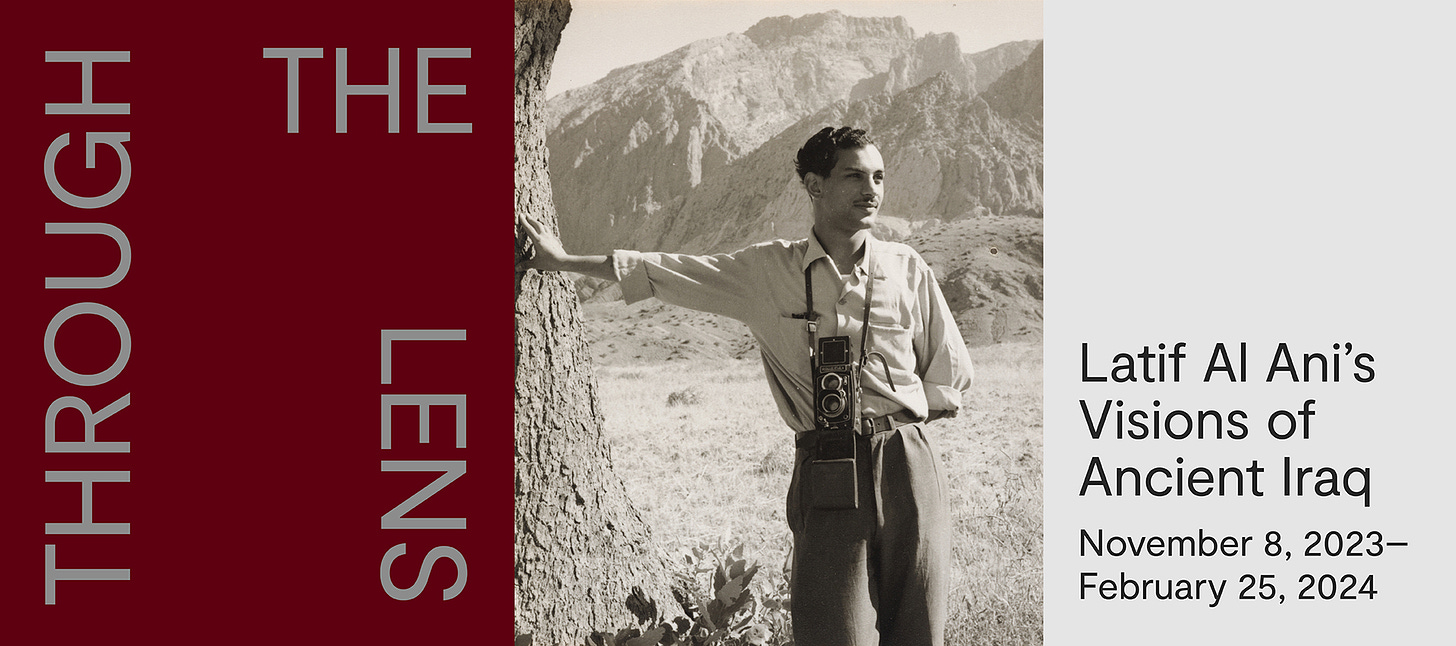

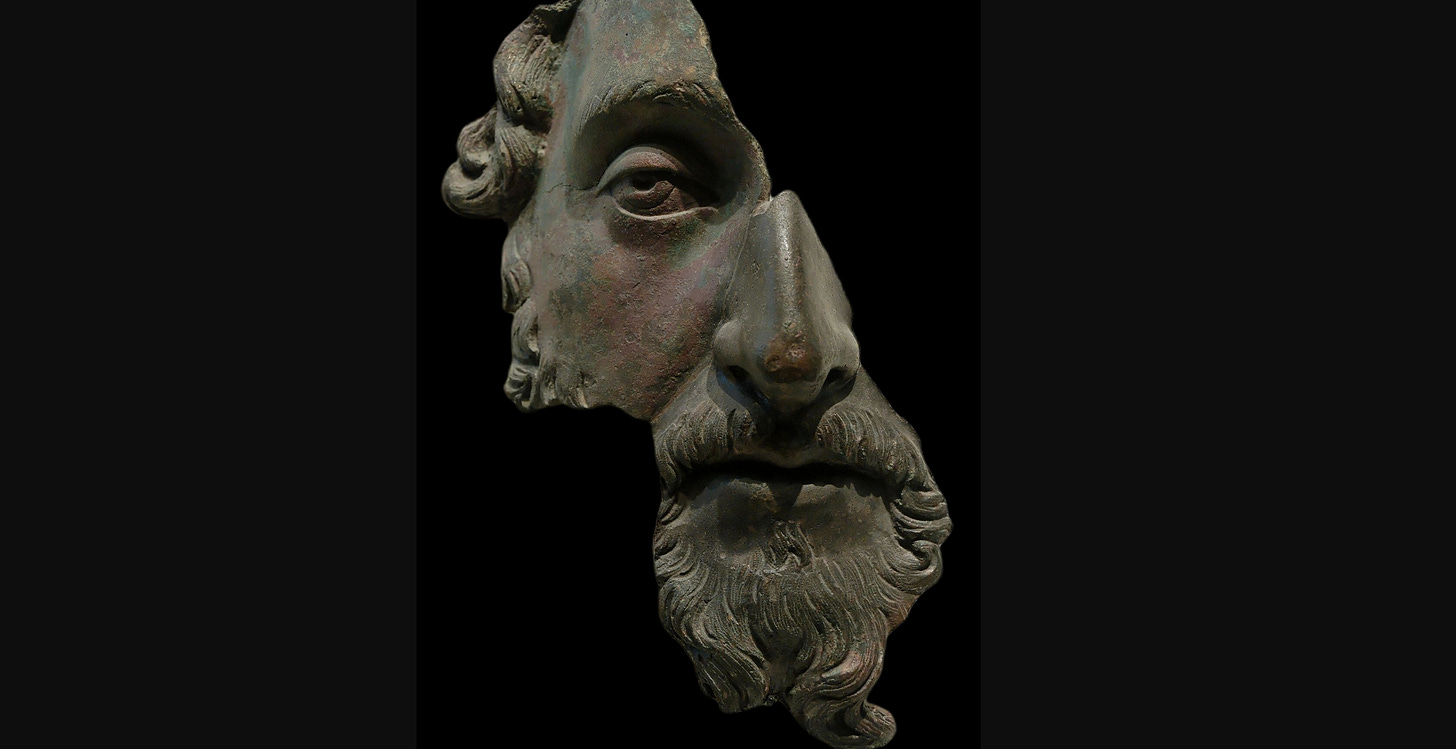

The exhibition "Through the Lens: Latif Al Ani’s Visions of Ancient Iraq opens next Wednesday (November 8, 2023) at the NYU’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. It displays the work of Latif Al Ani (1932-2021), the founding father of Iraqi photography.

The Index of Medieval Art announced that they will be holding an online training session for anyone interested in learning more about the database. It will take place via Zoom on Tuesday, November 14, 2023 from 10:00 – 11:00 am EST.