Pasts Imperfect (11.16.23)

Gladiators and AI, Aztec Daily Life, Ancient Coin Hoards Galore, and More

This week, ancient historian Sarah E. Bond draws on the flaws of pop history and AI to teach antiquity, with some help from gladiator expert and classicist Kathleen Coleman. Then, reviewing a new book on public slavery in Roman antiquity; a newly digitized manuscript provides insight into Aztec daily life; coin hoards in Sardinia and Japan; uncovering the eastern Achaemenid Empire; a classicist uncovers deep debt at the University of Chicago; addressing Blackness and African diaspora through stories about Memnon, Andromeda, and Chariclea; new ancient world journals, and much more.

On Gladiator, AI, and Responsible Pedagogy by Sarah E. Bond

In the spring of 2023, I was dismayed to find that a number of students appeared to use the generative AI program called ChatGPT to write their response papers for a large lecture course I teach at the University of Iowa on the ancient and medieval Middle East. My TAs didn’t need an AI detector to know something was amiss, and the detectors confirmed our suspicions. The citations were bungled and often did not match the rather bland, C-level analysis. “But how could this happen?” I fumed. I had banned it on the syllabus, after all. In office hours, a number of my students copped to using it. Others stood firm that they had not, despite evidence to the contrary. In that moment, both my naïveté and the new normal came into focus. AI was here to stay in the college classroom.

From Augustan social legislation to the Price Edict of Diocletian: ancient historians know all too well that just because a law exists, it does not mean people follow it. An expansive gulf can form between regulation and reality. And the fact is that a new study shows that over half of students already use AI, while only 25% of faculty do. But could I have students engage with the faults, biases, and citational blunders in AI responsibly? I began to make some changes to my Roman Empire course, set to be taught in the weeks that I returned from maternity leave.

The first assignment I modified was my yearly review essay for the movie Gladiator (2000). After watching the film, students were normally asked to write a movie review that listed the errors and ahistorical choices made (e.g., the use of stirrups or the idea that Marcus Aurelius wished to bring back the Republic). This time, I formulated a new assignment wherein I asked students to ask ChatGPT what the historical errors were, and then go through the AI list to fact check it with primary and secondary sources. Ancient history is about source criticism, after all. It was time that students practiced some Quellenkritik of their own.

I discussed the formation and results of this assignment for an essay over at Hyperallergic this week. Writing it up also gave me the chance to reach out to someone I had long admired: Harvard ancient historian Kathleen Coleman. It was her work to try and make changes to Gladiator during its production that had inspired the original assignment in my class. And yet, in my discussion with her, I was more captivated by her use of AI in her “Loss” course. As always, Coleman was already at the cutting edge of academia, incorporating AI as a means of showing students the strengths that lie in human writing.

As I note in the essay, for one assignment, Coleman asked students to compose letters of condolence. She contributed one herself, to a friend whose adult daughter had died of cancer, and asked the students to critique it, which they did with gusto. Afterwards, she told them that it had been written by AI. “ChatGPT did an absolutely appalling job and the students just ripped the thing to shreds,” Coleman told me. The lack of emotion and humanity, she remarked, “made them realize that AI is so generalized, so cliche-ridden, and has absolutely no sensibility. It went on for more than a page, in hundreds of words of nothing but blabber.”

As it turned out, humans are pretty good at sussing out which “thoughts and prayers” come from a genuine — and human — place.

Speaking to Coleman was pedagogically inspiring. She’s generous with her time and expertise. It also renewed my appreciation for how hard historical consultants work to get their voices heard. From Robin Lane Fox to Monica Cyrino to Adrienne Mayor, academics have a role to play in popular media and the popular imagination. Even if Hollywood studio executives won’t listen in the end, we should still offer our advice. Likewise, we can work with and not against AI. ChatGPT is no more a death knell for scholarship and teaching than the rise of Wikipedia was. Just as many of us began to assign films like 300 alongside primary readings from Plutarch, we can train our students as source critics so that they can recognize the flaws produced by new types of technology and in mass media.

Meeting people where they are is part of effective teaching. In the face of AI’s rising popularity, we can retreat to bluebooks and oral exams and AI bans and tell ourselves we’re safe, we have kept our disciplines “pure.” But our students, who live in the world beyond our syllabi, will keep moving past those choices. If we want them to talk with us, we might consider walking alongside them.

Public Scholarship and a Global Antiquity

In the new issue of The Classical Review, ancient slavery scholar Javal Coleman reviews Franco Luciani’s Slaves of the People. A Political and Social History of Roman Public Slavery (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2022). In his remarks on this much-needed study of Roman servi publici, Coleman notes the broad evidence compiled in the book. “One of the most useful aspects of the work is the collection of all literary and epigraphical evidence that mentions public slaves,” he says. “This is split between six appendices, which fill 171 pages. The appendices alone will serve as a useful source not only for historians of public slavery, but also for those interested in Roman slavery and epigraphy more broadly.” For more on public slavery in antiquity, see recent work on ancient Greek public slavery by Paulin Ismard and Noel Lenski’s research on their status in Roman Late Antiquity.

Divers off the coast of Sardinia discovered a hoard of 30,000 to 50,000 Roman coins dating from the reign of Constantine up to 340 CE, three years after his death. The Associated Press notes that “firefighter divers and border police divers” were also involved in the recovery effort to get the coins from the sea floor. The video below (and swelling music) captures the discovery on film.

In other numismatic news that goes one louder: 100,000 ancient coins were discovered in Maebashi, in the Gunma Prefecture of Japan: “The oldest coin examined was a Ban Liang — a bronze coin that dates back to the Chinese empire in 175 BC — and the most recent dated to 1256, per Asahi Shimbun. The oldest coin found was engraved with the words "Ban" and "Liang" and had a hole in the middle.” The coins were likely buried in the Kamakura Period (1185-1333).

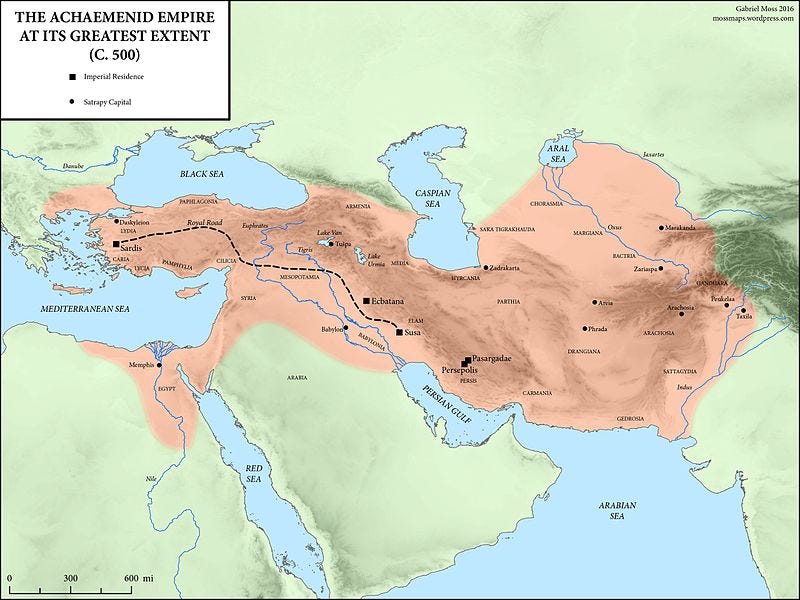

Over at Bryn Mawr College, they have a new profile of Wu Xin, Assistant Professor of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology. Wu researches “ancient Mesopotamia, across the Iranian Plateau, towards Central Asia and China” during the Achaemenid Persian period (6th-4th centuries BCE). As they note, she is at work on a book called Persia and the East, which analyzes the Achaemenid imperial system in its eastern provinces. Few studies look at the eastern half of the Achaemenid empire, which is emerging more and more thanks to archaeological fieldwork. Also check out her chapter in the open access volume The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World, where Wu looks at “Central Asia in the Achaemenid period.”

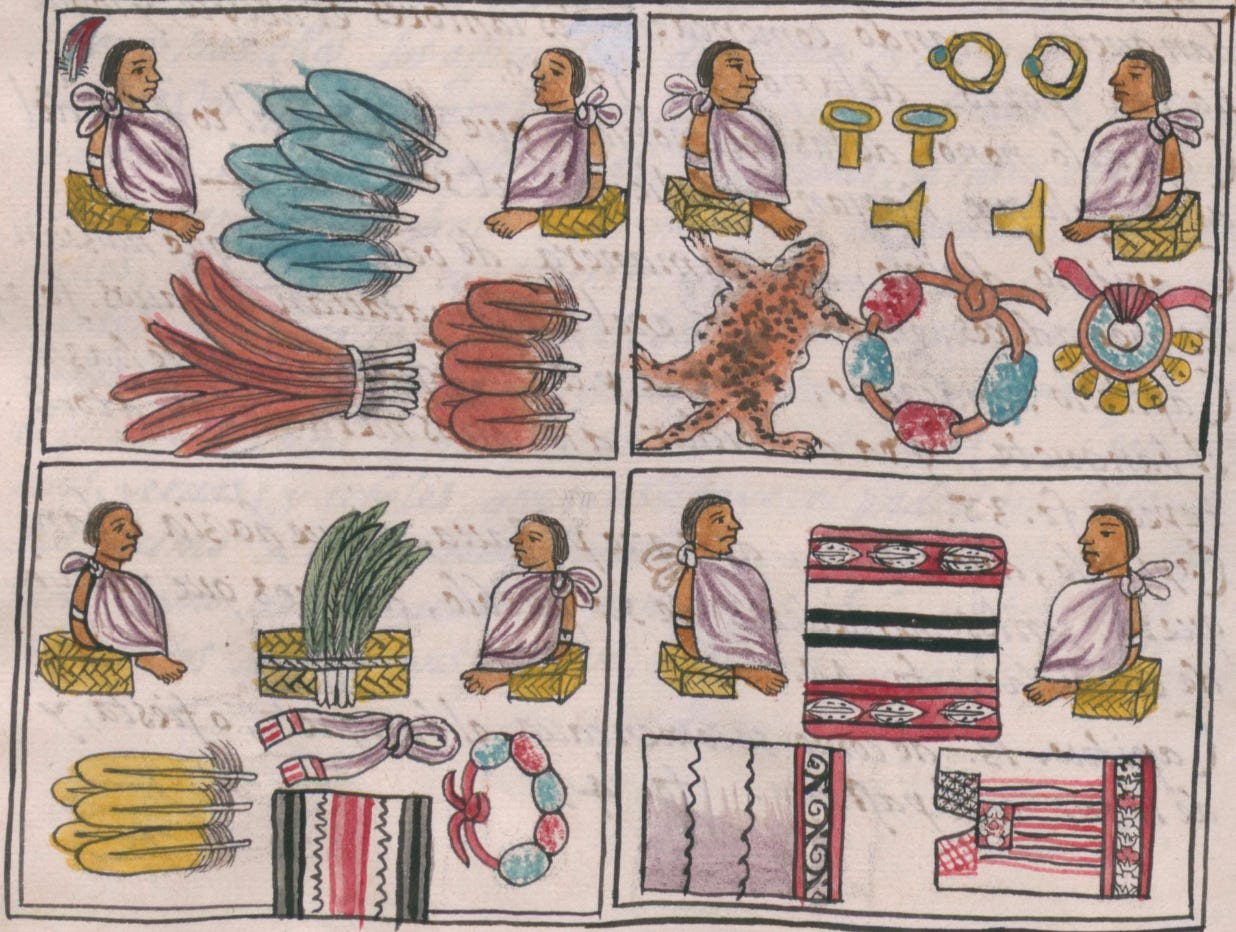

After seven years of digitization and research work, the Getty Research Institute unveiled the Digital Florentine Codex, a “Sixteenth Century Encyclopedia of Indigenous Mexico.” As they remark, the manuscript was created by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and a group of Nahua elders. It was finished in 1577. It provides insights into Aztec daily life, religion, and Mexica culture. The manuscript was then sent to the Medici in Florence, and thus acquired its name.

In the week leading up to Diwali on November 12th, The Asian and Asian American Classical Caucus had some great member spotlights on their socials. Check out profiles of Pramit Chaudhuri, Ethan Ganesh Warren, and Lylaah Bhalerao.

The Journal of the History of Ideas Blog features a think piece by Diptarka Datta, “Their Civilization—Whose Archaeology?” explores the political role of archaeology in post-colonial India and Pakistan.

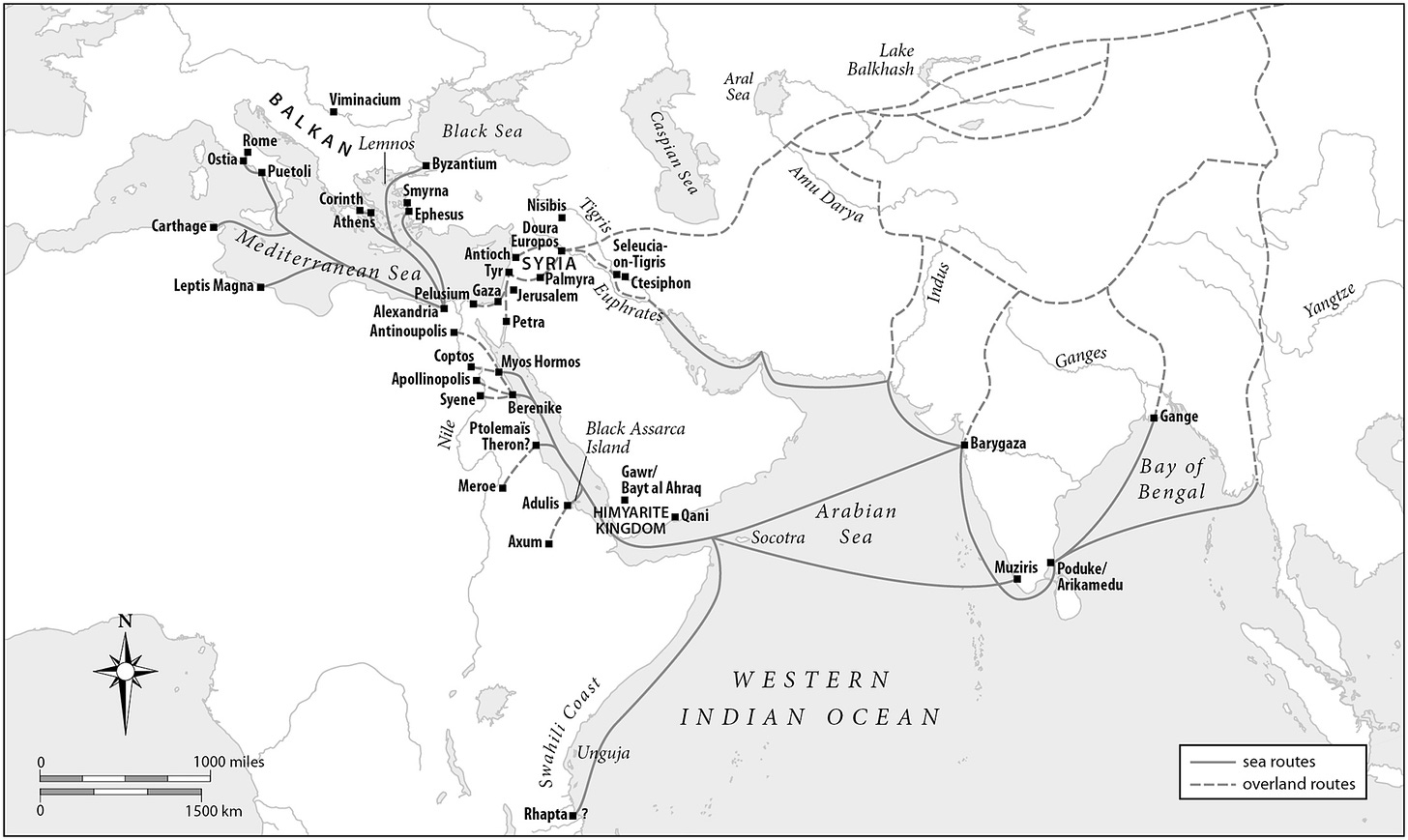

There is a new open access article in The Journal of Interdisciplinary History by Sabine R. Huebner and Brandon T. McDonald which looks at “Egypt as a Gateway for the Passage of Pathogens into the Ancient Mediterranean.” As they note, “The region south of Egypt developed a pestilential reputation, due in part to Thucydides’ account of the Plague of Athens, which traced the disease’s origins to that area. Later records are modeled on Thucydides’ account, muddling the true origins and scope of later outbreaks. Critical reading of ancient literature and documents—particularly papyri—supplemented with archeological and palaeoscientific evidence, significantly improves our understanding of how Egypt facilitated the circulation of pathogens between the western Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.” They ask an important question regarding how and why we must separate topos from reality when analyzing ancient diseases.

In the Annual of the British School at Athens, Anna P. Judson has an open access article on reconstructing the work of the Pylos tablet-makers who produced the Linear B tablets. Judson “combines experimental archaeology with autopsy of the tablets from Pylos” to reconstruct the relationship between “making” and “writing” these important tablets.

Members of the Black Trowel Collective and archaeologists Marian Berihuete-Azorín, Chelsea Blackmore, Lewis Borck, James L. Flexner, Catherine J. Frieman, Corey A. Herrmann, and Rachael Kiddey, have a new open access essay: “Archaeology in 2022: Counter-myths for hopeful futures.” As they note in their abstract, these anarchist archaeologists are ready to deconstruct some myth and provide some new possibilities for the future.

Emily Austin discusses the often misunderstood philosophy of Epicurus and its relevance to contemporary life with Gregory LeBlank at the unSILOed podcast.

At Publisher’s Weekly, they speak to historian of the Bible and Late Antiquity Andrew S. Jacobs about his forthcoming book, Gospel Thrillers: Conspiracy, Fiction, and the Vulnerable Bible.

He’s collected dozens of fear-and-conspiracy-ridden novels in which the Biblical text—as well as the truth and authority Christians find in Scripture—comes under threat. These novels were written between 1940 and 2020 amid World War II, the Cold War, the 9/11 attacks, and the explosion of social media with its capacity for misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories about the government and society. Keeping the times in mind, Jacobs explores the fascination with biblical thrillers and how they affect perceptions of the Bible

🚨 Finally, at the University of Chicago, Classics professor Clifford Ando sounded an alarm about the financial state of the university—and warns they should not cut humanities and social science programs to address the debt they are taking on. The Chicago Maroon reports, “According to Ando’s paper, the University’s debt grew from $2.236 billion in 2006 to $5.809 billion in 2022, which represents an increase of 260 percent. High levels of debt present a financial problem for the University because of rising interest payments. The University paid $45.7 million in interest payments in 2006. Ando claimed that payments averaged $200 million in 2021 and 2022.” 🚨

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib / yaleclassicslib.bsky.social)

Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde Vol. 50, No. 2 (2023)

Philologus Vol. 167, No. 2 (2023) Michael Pope, “Honey and the Indecency of Epicurus’ aurea dicta (DRN 3.12)”

Klio Vol. 105, No. 2 (2023)

CIPEG Journal Vol. 7 (2023) #openaccess

Archäologischer Anzeiger No. 1 (2023) #openaccess NB Paul Pasieka, et al. “The Hidden Cityscape of Vulci”

American Journal of Legal History Vol. 63, No. 1 (2023) Status in Ancient and Medieval Law

Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy Vol. 37 (2023)

Annual of the British School at Athens Vol. 118 (2023)

New issue of the International Journal of Cultural Property Vol. 30, No. 2 (2023)

Opuscula Vol. 16 (2023) #openaccess

History of Humanities Vol. 8, No. 2 (2023)

Studia graeco-arabica Vol. 13 (2023) #openaccess

Arabic Sciences and Philosophy Vol. 33, No. 4 (2023)

Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures Vol. 12, No. 2 (2023) NB Todd R. Hanneken “What to Think about When Thinking about Digitization of Manuscripts”

Gephyra Vol. 26 (2023) #openaccess NB Murat Tozan “Physiognomy and Geosophy of Pergamon according to Aelius Aristeides”

Journal of Historical Network Research Vol. 9 (2023) #openaccess Networks of Manuscripts, Network of Texts

thersites Vol. 17 (2023) #openaccess Classics and the Supernatural in Modern Media

Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus Vol. 21, No. 3 (2023)

Advances in Ancient, Biblical, and Near Eastern Research (AABNER) Vol. 3 No. 2Material and Scribal Scrolls Approches to the Hebrew Bible (2023) #openaccess

Manuscripta Vol. 66, No. 2 (2023)

Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie II, Historia Antigua Vol. 36 (2023) #openaccess

Internet Archaeology No. 63 (2023) #openaccess Digital Archiving in Archaeology

Revue des Études Byzantines Vol. 81 (2023)

Ancient Philosophy Today Vol. 5, No. 2 (2023)Ancient Philosophy of Mathematics and Its Tradition

Dumbarton Oaks Papers Vol. 77 (2023) #openaccess NB Przemysław Marciniak “Byzantine Cultural Entomology (Fourth to Fifteenth Centuries): A Microhistory of Byzantine Insects”

Online Lectures, Events, and Exhibitions

On November 23, 2023, Judith Olszowy-Schlanger will speak on her new book. You can hear more about “Learning Hebrew in Medieval England” at the zoom lecture sponsored by the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies. It starts at 6:00 pm UK time (12:00 pm CT).

On November 29, 2023, Mai Musié invites you to join a great collection of scholars for the first online event in a series of discussion workshops “exploring migration and Blackness in Northeast African diaspora communities through Ancient Greek storytelling.” Register at Eventbrite for the conversation, “Memnon, Andromeda, and Chariclea: Exploring Migration and Blackness,” which will also feature Awet Araya, Yoseph Araya, and Sarah Derbew.