Pasts Imperfect (10.5.23)

Christian (?) Food, Roman Army Victuals, a Questionable Mirror, & More

This week, archaeologist Lorraine Abagatnan discusses food history and the difficulties in recovering early Christian identities. Then, more Christianity (the original and the remix), more food, a conversation about translation, the Nazi and Fascist obsession with the collection of antiquities, and we voice our suspicions about that “courtesan’s” mirror found in Israel.

Food and Identity in Early Christianity by Lorraine Abagatnan

As a woman who identifies as a bona fide Southern Californian, I do, actually, live up to the stereotype of drinking any form of milk that doesn’t come from a cow. Almond, oat, hemp, soy—literally anything besides actual milk. Spending an extra $5 to get the “fancy” milk–accompanied with avocado toast, from time to time–creates an association between me and the sunshine state of California. In this case, the association is true, but as a historian of food and archaeologist, I’ve found myself reflecting on how food stereotypes like these come about.

In antiquity, the Gallic drinking of cow’s milk was seen by Romans as “barbaric.” But what am I saying today? Am I really signaling a serious commitment to my health and wellness (important values to those residing in the Golden State), or is it more a matter of public perception? I’ve concluded that we’re more or less obsessed with caring about what others eat, even if it really isn’t our business. Why else do we have adages like “you are what you eat”? It’s difficult to determine which aspects of human life are really universal and diachronic, but our conceptions around food seem to be pervasive over time.

This is why food makes for an interesting lens of study in its own right. For scholars of antiquity, how we’ve approached food has changed drastically over the last few decades. Structuralists like Claude Levi-Strauss and Mary Douglas first established our understanding of food in its basic, economic definition as caloric intake to something bigger. To this extent, we still think of food in these terms, a lot of the time.

Most of our marketing around foods concern their nutritional facts, how well they contribute and cater to particular diets, or what kind of protection they can offer to ward off illnesses and even again. More recent scholars, like Christine Hastorf, however, have pushed the ways we think of food by highlighting its role in communal life, and even its use and ability to shape both personal and communal identities. This latter point is exactly what the milk alternative stereotype is about: Southern Californians drink anything but cow’s milk, apparently because… they’re from Southern California, and that means being obsessed with health…?

If you’ve raised your eyebrows at that last sentence, you might be intrigued to consider food and identity over time. As a scholar of both Early Christianity and archaeology, I have a hard time locating something concretely Christian in material culture prior to the 4th century. Something as multifaceted as ritual is particularly difficult to detect in early Christian communities, especially when we don’t always know what makes a place “uniquely” Christian.

Yet food is one concrete way of seeing Christian identity in formation. Take the Idol Food issue (1 Cor 8:1-11:1), for example. Described in Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians, it concerned the idea of Christians entering pagan spaces and consuming the food sacrificed to idols. Some Christians argued that the food couldn’t violate ritual practice, because it was sacrificed to idols and not to actual gods. Paul, however, stresses the importance of “strong” Christians setting a good example by abstaining from consuming this type of food,

By doing so, he notes that Christians are purposefully setting themselves apart from their non-Christian neighbors. Paul wanted Christians to avoid all things associated with idolatry, even with something as quotidian as food. Archaeologists have located structures like the Fountain of the Lamps in Corinth, whose architecture is suggestive of particular actions Christians may have taken in a pagan space. Because Christians would have entered the temple’s dining spaces by passing through the sanctuary–and seeing the idol food offered there–they would have needed make a real choice not to consume the food present there. What we see here is people like Paul, who were actively constructing the budding communal identity of Christians by laying out principles of good eating, which in turn reflected principles of good worship.

But let’s return to 21st-century California. Milk-drinking people don’t usually spurn the consumption of milk alternatives—certainly not in the way that some early Christians argued for eating idol food as a matter of religious orthopraxy. At the center of both of these examples, however, is the very real power of food in shaping the perceptions we have of ourselves, and the perceptions others have of us.

Food and the narratives around it really do have the ability to showcase ourselves and who we are in ways both mundane and meaningful. We think we shape food, but food shapes us in turn, too. Could we investigate food, both in textual evidence as well as material culture, to see how it shaped the peoples who lived long before us? My answer is a resounding “yes,” and I think we’d be surprised to see what we can find.

Public Scholarship and a Global Antiquity

At the Conversation, Chance Bonar discusses the Shepherd of Hermas. Little known today, it was an early Christian “best-seller”—widely read from the early 2nd to the 5th century of the common era. On a side note, while we are linking to this awesome essay, it should also be noted that medievalist and journalist David M. Perry has recently called out this non-profit media outlet for making $5 million in annual revenue—and yet not paying their writers. We’d second this emotion, particularly since The Conversation makes money from clicks and from partnering with universities.

Could someone please try this recipe for ancient Korean honey cookies out and tell us how it goes? We love anything by Eric Kim—absolutely check out his 2022 cookbook Korean American if you haven’t already—and these look amazing.

Geoff Manaugh at WIRED asks: what if we could scan the ground and see entire civilizations below us? And what if we could map it all with a machine that looks like a tricked-out lawnmower? As archaeologist Immo Trinks alleges when discussing ground-penetrating radar:

Every year, humanity loses more and more of its heritage. But now that entire landscapes can be mapped in a matter of days using off-road vehicles, the data processed in near real time with the assistance of feature-recognition algorithms and image-processing software, a tantalizing possibility comes into focus: We may be on the verge of a total map of all archaeology, everywhere on Earth.

Over at CNN Style, there is a review of Afro-Cuban American artist Harmonia Rosales’ exhibition “Harmonia Rosales: Master Narrative” at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta. As they note, a version of the exhibition was first shown last year at the AD&A Museum at the University of California, Santa-Barbara.

“[Rosales] is among those seeking to radically change [the] centering of Western ideologies as standard…The exhibition features seven years’ worth of work, as Rosales entwines the artistic techniques and hegemonies of European Old Masters, focused on Christianity and Greco-Roman mythology, with the characters, themes and stories of the Yorùbá religion.”

The publication last week of Emily Wilson’s translation of the Iliad has been accompanied by well-deserved fanfare. There is an intriguing conversation between Wilson and Madeline Miller at LitHub that is well worth a gander. Particularly interesting is the bibliography of translation inspirations to Wilson that she lists at the end:

I really enjoy reading Susan Bernofsky on her process as a translator of German novels—she has a great essay about revision. I’ve learned a lot from remarks about translation from the late-lamented Edith Grossman, translator of Don Quixote and many other classics of the Spanish canon. Lawrence Venuti, translator from Italian and Catalan, has written many thought-provoking books and articles about translation theory and practice, including his influential book The Translator’s Invisibility. I’ve learned a lot from the writings of both Michael Emmerich (translator of Japanese fiction) and Karen Emmerich (translator of modern Greek fiction). Ancient Greek and Latin were once living languages, too, so I think it’s important for a translator from those languages to think about how to make ancient literature feel as alive as it would have felt to an ancient reader or listener.

By the by, if you are interested in the art of translation, you might want to check out the open access journal Ancient Exchanges.

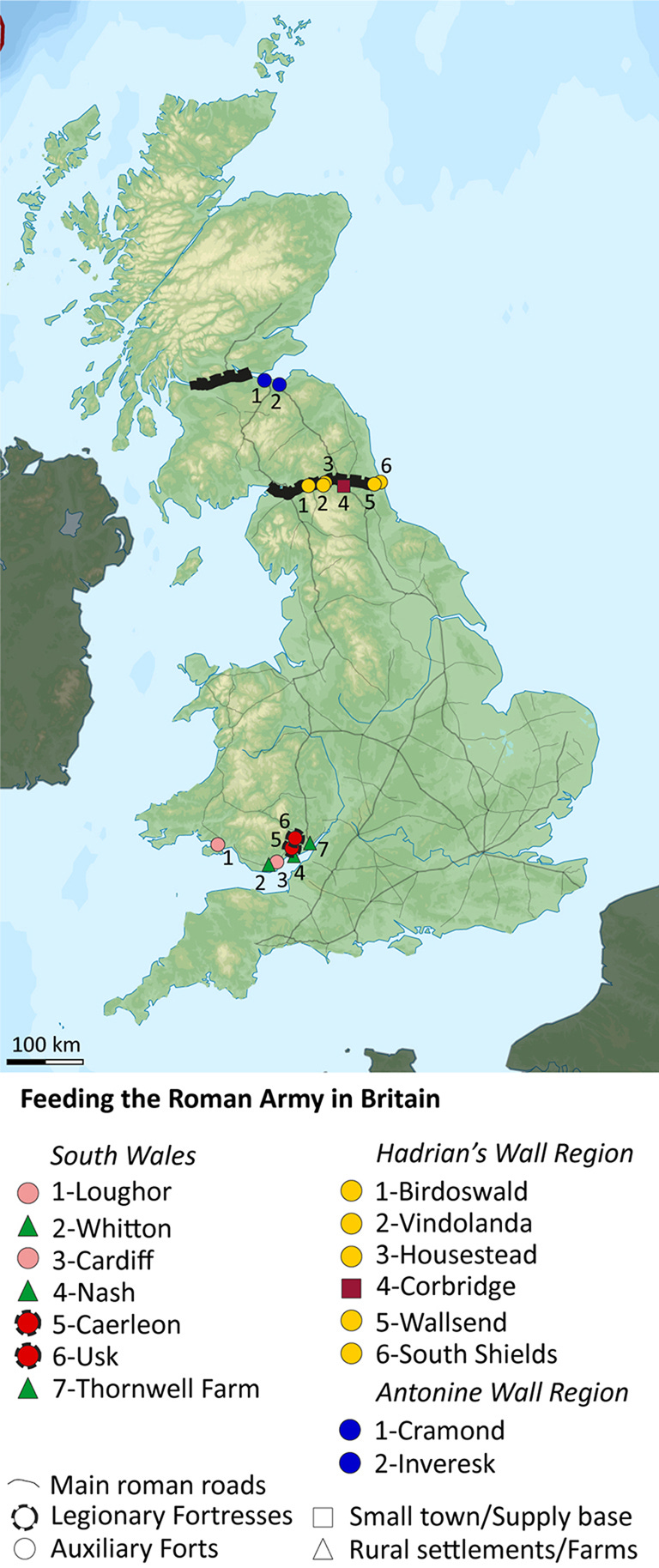

In a research project announcement in Antiquity, Peter Guest, Hongjiao Ma, Leïa Mion, Angela L. Lamb and Richard Madgwick discuss “Feeding the Roman Army in Britain.” Guest and his team note that the new project will ask: “How did the Roman Empire supply and maintain its frontier garrisons? What was the impact on populations and landscapes of conquered territories?” From strontium isotope analysis to identifying animal supply networks, this sounds like a fascinating exploration into the supply chain that fed around 300,000 soldiers.

A special, open access issue of the RIHA Journal is out, focused on "The Fate of Antiquities in the Nazi Era.” The issue is a collaboration of the Getty Research Institute and the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, and is guest-edited by Irene Bald Romano. Of particular interest is Daria Brasca’s chapter on, “The Role of Antiquities between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Diplomatic Gifting, Legal and Illegal Trades.”

Over at Live Science, there are new reports from the IAA that archaeologists in Israel have discovered a bronze mirror that may have been owned by a Greek ἑταίρα (hetaira) “who accompanied the Hellenistic armies on their campaigns.” The burial dates to between 399-200 BCE. It is notable that there is no inscription indicating she was indeed a ἑταίρα. Rather, the Israeli archaeologists are basing their assessment on the fact that she was buried away from others in a cave with nails and the mirror. This makes the identification far from completely certain. Moreover, the outdated translation of hetaira as a “courtesan” is—as Rebecca Futo Kennedy and Max L. Goldman, and many others have pointed out—quite outdated and anachronistic. One might be wary of jumping to conclusions in the case of this new Hellenistic discovery.

New Antiquity Journal Issues (by @YaleClassicsLib)

Acta Archaeologica Vol. 92, No. 2 (2021)

Mnemosyne Vol. 76, No. 5 (2023)

Classical Philology Vol. 118, No. 4 (2023)

Digital Classics Online Vol. 9 (2023) #openaccess

Pallas Vol. 119 (2022 #openaccess) Locus Ludi : quoi de neuf sur la culture ludique antique?

Eventum: A Journal of Medieval Arts & Rituals Vol. 1, No. 1 (2023) #openaccess The Arts and Rituals of Pilgrimage

Revue archéologique de l’Est (RAE) Vol. 71 (2022) #openaccess

Gnomon Vol. 95, No. 6 (2023)

Greece & Rome Vol. 70, No. 2 (2023)

Médiévales Vol. 84 (2023) #openaccess Guerriers du Nord

RIHA Journal 2023 #openaccess The Fate of Antiquities in the Nazi Era

Classical Receptions Journal Vol. 15, No. 4 (2023)

The International Journal of the Platonic Tradition Vol. 17, No. 2 (2023) NB Dorothea Frede, “Charles Kahn, 1928-2023”

Polis Vol. 40, No. 3 (2023) NB Otto H. Linderborg “Diffusion of Political Ideas between Ancient India and Greece”

American Journal of Philology Vol. 144, No. 2 (2023)

Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia Vol. 29, No. 1 (2023)

Mouseion Vol. 19, No. 3 (2022) NB Olivier Dufault “The Alleged Crisis of Classics and the Engagement with Theory in Ancient Mediterranean Studies: A Statistical Analysis of L’Année Philologique“

Interférences Vol. 13 (2022) #openaccess Mémoire(s) des conquêtes romaines, de la fin de la République à la fin du Moyen Âge

Greek and Roman Musical Studies Vol. 11, No. 2 (2023)

Analecta Bollandiana Vol. 141, No. 1 (2023)

Novum Testamentum Vol. 65, No.4 (2023)

Online Lectures, CFPs, and Current Museum Exhibitions

UVA Classics’ The Siren Project is pleased to invite you to the virtual lecture series “In Her Voice: Women’s Retelling of Greco-Roman Mythology.” Save the dates, and come listen to their amazing speakers! Details in the poster below.

On October 12th at 4:30pm EST, the Five College Renaissance Seminar will host the British Library’s Curator for Ethiopic and Ethiopian Collections, Eyob Derillo, discussing 'Illuminated Ethiopian manuscripts at the British Library.'

The Hill Museum and Manuscript Library just launched a new online exhibition “Writing in Tongues: Multilingual Books.” Curated by Josh Mugler, the exhibit explores the variety of ways in which historic books incorporated multiple languages. In addition, a new HMML website provides access to the Vööbus Syriac Manuscript Collection (60,000+ digitized images and more on the way).